In “Advanced Readings in D&D,” Tor.com writers Tim Callahan and Mordicai Knode take a look at Gary Gygax’s favorite authors and reread one per week, in an effort to explore the origins of Dungeons & Dragons and see which of these sometimes-famous, sometimes-obscure authors are worth rereading today. Sometimes the posts will be conversations, while other times they will be solo reflections, but one thing is guaranteed: Appendix N will be written about, along with dungeons, and maybe dragons, and probably wizards, and sometimes robots, and, if you’re up for it, even more. Welcome to the eighth post in the series, featuring Tim’s look at Roger Zelazny and the beginning of the Amber series.

Okay, let’s get into this.

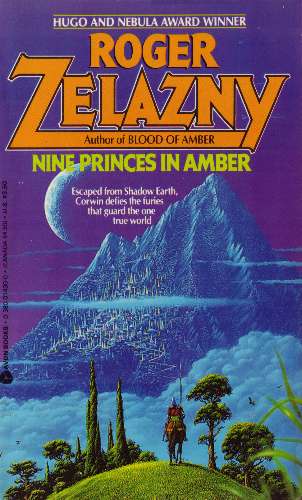

Though the complete Chronicles of Amber combine to form a towering ten volumes, I merely sampled the first book in the series, Nine Princes in Amber, originally published in 1970, and that was more than enough.

“Egads!” you may shout at me. “The Chronicles of Amber is a classic fantasy series, worthy of great acclaim and even worthy of its own Tor.com reread!”

That may be true, but if the first book in Roger Zelazny’s Amber series is considered any kind of classic, then it must be because the novel is graded on a curve. A curve called “pretty good for an opening novel in a series that gets a whole lot better,” or maybe a curve called, “better than a lot of other, trashier fantasy novels released in 1970, when there was nothing on television but episodes of Marcus Welby and the Flip Wilson Show to keep us entertained.”

I haven’t read the rest of the series, so I don’t know if it really does get better, though I suspect it must, once the protagonist actually starts to do something instead of floundering into trouble. And I don’t know every other trashy novel that came out in 1970, but I’m sure there had to be something of more merit than this one.

Nevertheless, I stand by my statement that the first of the Amber books is certainly less than what I would consider legitimately good reading.

It’s not that I found Nine Princes in Amber uninteresting; it’s just that I found the novel shockingly discordant and unsatisfying to actually read all the way through. It’s a novel that slams together jokey Hamlet references in the narration with pop psychoanalysis and superhuman beings and shadow realms and dungeons and swords and pistols and Mercedes-Benzes. That mixture could work, but like in Stephen King’s first Dark Tower novel, the clash of genre and ill-defined weirdness and too-homey familiarity just give the whole book an inconsistent tone, one that isn’t quite explained away by the protagonist’s foggy lack of awareness.

And since I’m looking at this book in terms of its influence on Dungeons and Dragons in addition to its merits as a novel in its own right, the only link I can see between Nine Princes in Amber and traditional fantasy role-playing games is that opening conceit: the amnesiac protagonist. It’s a story-starter not only used in tabletop gaming, where it removes the need for players to develop backstories before the first session, and “you wake up in a dank cell, and you can’t remember how you got there, or who you are” is an old standby, but it remains a common trope in video games as well. Skyrim begins with a minor variation on that old cliché, and it’s not alone.

Because other than that I-don’t-know-who-I-am opening sequence, the rest of Nine Princes in Amber is quite un-D&D like. Sure there are some of the elements of fantasy, like a dungeon that plays a role later in the story, but unlike a D&D dungeon, this one’s just a boring place for prisoners, hardly worth exploring at all. And though there are the pseudo-medieval trappings and ancient weaponry and the usual bits those setting details might entail, this isn’t a book about heroic deeds or monster-slaying or even solving mysteries and overcoming obstacles.

Instead, Nine Princes in Amber is about a man, Corwin, who gets screwed over by his brother, Eric. The plot of the entire novel is this: Corwin doesn’t know he’s a Prince of Amber—this magical shadow world—and he runs around trying to figure out who he is, and then he does, and he tries to overthrow Eric the Jerk, but he fails and ends up in the dungeon where he is sad. Spoiler alert: he escapes in the final pages.

That’s a complete novel according to the standards of 1970?

I should mention that the whole trying to overthrow his brother thing is not a whole lot of pages in the book. It’s mostly Corwin’s search for his identity and his crossing over into the shadow world. Then a brief fight that he loses. Then some moping around the dungeon.

What a weird structure for a novel. It’s more like three long chapters of a much larger book, presented as a stand-alone novel. Because Corwin escapes at the end, I guess this opening novel just presents the first act of the bigger story, but in the strata of novels about finding a hidden shadow world and seeking adventure there, it would rank pretty significantly below the heights of something like C. S. Lewis’s The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe or even Norton Juster’s The Phantom Tollbooth. Both of those stories, likely targeted for readers younger than Nine Princes in Amber, get their protagonists to the alternate reality realm rather quickly, by comparison, and establish reasons for us to care about what happens to the characters.

Roger Zelazny takes his time getting us there, and doesn’t make Corwin, or anyone else, worth rooting for. They just feel like pieces in his made-up game of Risk, where some of the playing pieces have been brought in from other games, like the race car from Monopoly and some playing cards from Aleister Crowley’s old deck.

Yet, as I mentioned earlier, Nine Princes of Amber isn’t without interest. It’s not at all compelling, but some of the ideas Zelazny attempts to explore evoke greater ambitions than what he’s able to successfully pull off in this first Amber book.

I may have mocked the hero-with-amnesia opening above, but Zelazny does push it a bit further than we usually see it done. He creates a sense of anxiety, only amplified in retrospect when we realize how powerful Corwin is, because it seems possible that the protagonist is insane. We don’t know how reliable his narration is—and it’s a first-person narration throughout—so we don’t know if we can trust our “senses” just as Corwin doesn’t know who or what is real and unreal. The nature of Amber, as a shadow world that overlaps into our own, makes the unreliability even more unsettling. Ultimately, we have to take Corwin’s word for what happens, because it’s the only point of view we have in this book, but Zelazny seems interested in the uncertainty of his protagonist’s reality. Or he at least seems willing to question it, even though the uncertainty undermines any confidence in what happens or why we should care. An approach that’s certainly unusual, but not necessarily effective as far as making the story matter to the reader.

The only other worthwhile bit of the novel revolves around the mystical device known as “the Pattern.” Zelazny plays with mythical resonances and Jungian archetypes throughout the novel—and, presumably, that approach continues in the sequels, or so a cursory glance tells me—and the Pattern, which is literally a pattern on the floor but also a kind of trans-dimensional psychic gauntlet (if I understand it correctly), is Corwin’s passage back into his true self. His memories return and he locks back into his role as a Prince of Amber, even if the political structure has changed since he last departed for his Earthly journey. The Pattern, along with the notion that the hierarchy of Amber is kind of its own Tarot deck (with character-specific cards named in the novel), provides exactly the kind of narrative hook to make Nine Princes in Amber engaging. The crucible of the Pattern is the kind of drama and revelation that Zelazny can’t match in the rest of the novel, though the book desperately needs more of that stuff and less of the driving around looking for Amber and the talking about how bad everything’s gotten because Eric’s around.

I will admit that Corwin’s escape, which is also the first time he actually feels like the protagonist of the novel—someone who is ready to take action on his own—almost made me want to keep reading and continue on to book two of the Amber series, The Guns of Avalon. But even after the relative brevity of Nine Princes in Amber, I feel Zelazny-ied out. Maybe I’ll feel differently about his inconsistent prose and uncomfortable structural choices if I read all five books in the Corwin cycle, if not all 10 of the Amber series. Then again, maybe it will just be more of the same.

If you’ve read any of this stuff, let me know what you think, because I don’t see much here to compel me to continue any deeper into the realm of Amber.

Tim Callahan usually writes about comics and Mordicai Knode usually writes about games. They both play a lot of Dungeons & Dragons.