In this bi-weekly series reviewing classic science fiction and fantasy books, Alan Brown looks at the front lines and frontiers of the field; books about soldiers and spacers, scientists and engineers, explorers and adventurers. Stories full of what Shakespeare used to refer to as “alarums and excursions”: battles, chases, clashes, and the stuff of excitement.

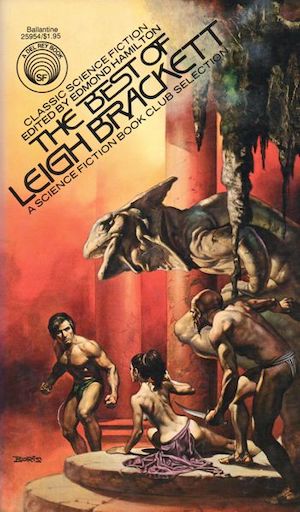

I have long been a fan of Leigh Brackett, but rarely found her books on the shelves of bookstores. Every time I found one of her stories, usually in an anthology, I said to myself, “I need to keep my eye out for more of this.” In recent years, I’ve ordered a few of her books over the internet. And just a few weeks ago, at my local used bookstore, I found a treasure that had long eluded me: the Del Rey Books anthology The Best of Leigh Brackett, edited by her husband, Edmond Hamilton. And what a joy it was to read. It contains a lot of classic planetary romance stories, along with strong samples of her other science fiction for good measure.

There is a certain thrill in searching the shelves of a good bookstore—perhaps it is an atavistic impulse, rooted in human genes, echoing the thrill of a hunter/gatherer when food is discovered. And I felt that thrill a few weeks ago when I walked into my favorite used bookstore, Fantasy Zone Comics and Used Books, and Julie said, “We just got something I think you’ll want to see.” And there among the boxes of newly acquired books, I found a treasure: seven books by Leigh Brackett, three I had read and lost track of, and four that were new to me. Keep your eyes open in the coming months, as I plan to visit these works from time to time, paying well-deserved homage to a pioneer of the field who does not get enough credit these days.

About the Author

Leigh Brackett (1915-1978) was a noted science fiction writer and screenwriter, perhaps best known today for her work on the script for Star Wars: The Empire Strikes Back. I’ve reviewed Brackett’s work before—the omnibus edition Eric John Stark: Outlaw of Mars, the novel The Sword of Rhiannon, the novelette “Lorelei of the Red Mist” in the collection, Three Times Infinity, and the short story “Citadel of Lost Ships” in the collection, Swords Against Tomorrow—and you can find more biographical information in those reviews.

Like many authors whose careers started in the early 20th century, you can find a number of her stories and novels on Project Gutenberg, including some of the tales featured in this anthology.

One Person’s Cliché Is Another Person’s Archetype

The writers of planetary romance often had their work looked down upon by critics. Their characters were accused of being clichéd, their plots of being derivative, and their settings were frequently shared with other authors. But while some elements were common from tale to tale, the readers also expected them to present new and exciting marvels, mysterious creatures, scientific wizardry, and epic struggles.

The pulp authors had to create these grand tales within tight word count constraints. They were not afforded the luxuries of fine artists or painters, able to take their time and painstakingly fill their works with grand vistas and precise details. Instead, they were like skillful sketch artists, bringing their vision to life with a few broad strokes. They had to create their worlds using familiar tropes and character types, allowing readers to fill in the detail using their imaginations. They also used archetypes and images from folk stories and mythology, which could be quickly conveyed to a reader familiar with those old tales. And sometimes, of course, a sketch can have power and energy a more deliberately painted work might lack.

Brackett’s work uses these tools of the pulp trade. While there are surprises and variations, a great deal of her planetary romance work follows familiar templates; the protagonist being called to a mission, facing strange creatures and mysterious cities, with some sort of evil villain—often from a dying race—at the center of things. Unlike the young characters of a standard “hero’s journey,” Brackett almost uniformly uses protagonists who are older, experienced, and often world-weary or beaten down by life. And while the adventures are brutal, and the protagonists suffer grievously throughout, Brackett’s tales frequently end on an optimistic note. There is often love found along the way, riches attained, and even the hardest of protagonists seem to possess a streak of nobility. I have also long noticed that Leigh Brackett was prone to using Gaelic names for characters and places, and that some of her stories echo Scottish and Celtic mythology. In her afterward to this collection, I found her referring to the fact that she was “half Scots and inclined to ca’ canny” (caution or carefulness). Her pride in that heritage comes out in her work.

One feature of this collection I enjoyed was that it offers an opportunity reading some of Brackett’s non-planetary romance work. We get a few tales set on our own world, and we see Brackett adapting these settings to her plots and characters as easily as she used those of planetary romance. The characters here are less like heroic archetypes, and resemble people we might meet in our own lives. The prosaic details that root the stories in the real world sometimes date them, as the culture has evolved in the past decades, but the stories still ring true.

The Best of Leigh Brackett

One of the best features of the book is the lovely introduction by Brackett’s husband, Edmund Hamilton, as well as the afterword by the author herself. Fans are given some insight into the working styles of these two very different authors, and their obvious love and admiration for each other. And Hamilton offers readers some interesting information on how he selected the specific tales for the volume.

The first tale, “The Jewel of Bas,” is a story rooted firmly in the planetary romance tradition. It follows the adventures of the harpist bard Ciaran and his wife Mouse. They venture onto the Forbidden Plains and find that legends of the immortal Bas, his servant androids, and the beastlike Kalds who serve him—legends Ciaran had long sung about—are true. They are captured and put to work along with other humans building a huge device with an inscrutable purpose. This story is rooted in Celtic myth, but also mentions lost Atlantis and evokes the myth of Orpheus and Eurydice. It puts the two protagonists in a brutal and seemingly impossible situation that they must somehow escape, using their strength, determination, and the power of music.

“The Vanishing Venusians” follows a colony of Earth colonists whose village was destroyed, and who now wander the seas of Venus, searching for a home. They find an island, and three men climb the cliffs around it in order to explore: the old and bitter Harker, the young married man McLaren, and a black man, Sim. Sim sings old spirituals about the Golden City and the promised land, tying their quest to biblical themes. In underground passages, they are attacked by plant-like aquatic creatures, and Sim becomes the first to fall, sacrificing himself to help the others, a Christ-like image. They then find the plateau inhabited by a kind of flower people, initially attractive, but ultimately dangerous. They find a way to pit the two strange races against each other, and Harker also sacrifices himself. In the savage wilderness of Venus, the rule is kill or be killed, and the price of salvation for some is genocide for others.

“The Veil of Astellar” is set in space, but has the feel of a planetary romance. A hard and bitter man meets a young woman who reminds him of an old love, and he tells her his name is J. Goat, thinking to himself that the J stands for Judas. Both will be traveling on the spaceship Queen of Jupiter, through a region referred to as the Veil of Astellar, where ships have been disappearing. The man, who was on a previous vessel, lost generations ago, is one of those who leads these ships to their doom at the hands of malevolent aliens. In return, he has gained an incredibly long and privileged life. But when he learns that the girl he left behind had been pregnant, and the young woman he just met is family, he begins to regret that bargain…

In “The Moon that Vanished,” we meet Captain David Heath in a drug den, a bitter and defeated man. But he has customers who want to charter his sailing ship so he can lead them to the Moonfire, the remains of a small moon that had long ago fallen, which can allegedly grant people incredible powers. Heath had found and touched the Moonfire once before, and the experience left him broken, destroyed like Icarus for his hubris. The Moonfire is guarded by the fanatical priests known as the Children of the Moon. Heath’s customers are an ambitious man and a beautiful woman who controls a savage flying dragon. The sea journey to the Moonfire is vividly described, and full of adventure and close escapes. And when the destination is reached, there is a surreal journey into the heart of the Moonfire—a journey that will change David Heath forever.

One of the longest and best tales in this collection, an adventure starring Brackett’s recurring character Eric John Stark, is “Enchantress of Venus.” This story has a lot of mythical overtones, evoking Orpheus in the underworld (but without the music), and the Harrowing of Hell (but without the divinity). The tale takes place in the same area of Venus as “Lorelei of the Red Mist,” in the Red Sea of thick breathable gasses encompassed by the Mountains of the White Cloud. The warrior Stark is searching for a friend who disappeared from a town on the shores of the sea. In his own headstrong fashion, he follows his friend’s path, only to be captured himself. Stark is enslaved in a ruined city submerged in the red mists, locked in a collar that will kill him if he attempts escape. A twisted and evil family is searching for an ancient secret they think will give them the power to rule the entire planet. That the unstoppable warrior will ultimately win out is not a surprise, but the twisty path to getting there makes for a dark but enjoyable tale.

“The Woman from Altair” is my favorite tale in the collection, a story that is different in tone and structure from the others. Instead of planetary romance, it is a murder mystery set on Earth. The oldest brother of a spacefaring family has been injured, and cannot take up the family business. But he can manage it from Earth, and greets his younger brother returning from Altair with a shipload of trade goods, who introduces an alien woman as his new wife. A reporter ingratiates herself with the older brother, and at first appears to be using him to get her story. But then animals begin to violently attack their owners, and soon there is a death. The identity of the murderer is not the mystery; instead, it is the “how” and “why” that keep us guessing. No one in the story turns out to be who they initially seem to be, and the way the narrative unfolds is fascinating. The story serves as a good indication of why director Howard Hawks selected Brackett to co-write the screenplay for The Big Sleep.

“The Last Days of Shandakor” follows the adventures of John Ross, an archaeologist on Mars desperately trying to make a name for himself. He pays a man to take him to the lost city of Shandakor, and while it first appears to be inhabited, he finds the city has become a necropolis, filled only with ghosts of the past, and ruled by an evil creature from a lost race. Ross escapes joining the dead and achieves fame and fortune, but ends up feeling that he’s lost far more than he gained.

The setting of “Shannach—The Last” is the planet Mercury, which in the days of planetary romance was thought to be tidally locked with the sun, possessing a thin inhabitable twilight belt between the light and dark sides. A prospector, Trevor, searching for invaluable jewels called sunstones, crashes and just barely finds his way to a lush and previously unknown valley, controlled by human troops and flying lizards who wear sunstones on their foreheads. He falls among other humans who have escaped from the troops, and learns that the sunstone wearers are under the telepathic control of an ancient being called Shannach, the last of his race. Trevor falls under the control of Shannach himself, but fights free and makes a desperate escape across the airless peaks in a makeshift spacesuit. By the end of the story, while the lonely Shannach has done cruel things, I felt a bit of pity for the creature.

A spacefaring uncle returns from Mars in “The Tweener” with a gift for his niece and nephew. It is an indigenous animal he thinks will be a good pet (a practice common when explorers visited the far corners of the Earth, this would be unthinkable today, with all the protocols in place to prevent contamination, outbreaks of invasive species, etc.). His brother begins to have doubts about the gift, and wonders about the effect the pet is having on the children. At one point, I thought the story was going in the same direction as “Mimsy Were the Borogoves,” an older tale by another married writing team, Henry Kuttner and C. L. Moore. But the story moves in its own way, and ends on an uncomfortable note that would be perfect for an episode of The Twilight Zone.

“The Queer Ones” is another story set on Earth, where a local newspaperman and doctor in a mountainous backwoods region have discovered a child who is clearly not a normal human. They initially believe that he is some sort of mutation. But then the people looking into the situation begin to die in mysterious circumstances, and the newspaperman discovers the truth is even stranger than he thought. The story is filled with mystery, and leaves the reader wondering how much other strangeness might be hidden away in the nooks and crannies of our world.

Final Thoughts

Leigh Brackett had a long and interesting career, split between the world of pulp science fiction (which she loved), and the world of Hollywood (which paid well, when it paid). She was a master of pulp science fiction and wrote a lot of it—not because it was the best she could do, but because she enjoyed it. Her heroes were compelling, the settings exotic and cleverly crafted, and the challenges they faced seemingly insurmountable. I have felt a lot of different things in the course of reading her work, but I have never been bored.

And now, as always, it’s your turn to chime in: Have you encountered any of the tales in this anthology, and if so, what are your thoughts? Are you, like me, a fan of planetary romance? Are there other tales of adventure that you would also recommend? I look forward to hearing from you in the comments.

Alan Brown has been a science fiction fan for over five decades, especially fiction that deals with science, military matters, exploration and adventure.