Akira Kurosawa, Japan’s preeminent film director, has influenced just about every genre of film making in the west, especially westerns and action films in general (though some of Kurosawa best movies, I believe, are slower and more personal, such as Ikiru and Dodes-Kaden). Everyone from Sergio Leone to George Lucas to John Lassiter has drawn on his work.

Naturally, Kurosawa had his own influences as well. A voracious reader, he loved Georges Simenon. Stray Dog began as a novel, Kurosawa’s attempt at a Maigret-style detective story. Kurosawa felt his story didn’t succeed as homage to Maigret. I don’t know Simenon’s work well enough to compare, but I find the film (which Kurosawa adapted from his own unpublished novel) succeeded wonderfully on a number of other levels.

Stray Dog takes place in a summer heat wave during the American occupation. Though there is not a single Caucasian face in the film as far as I could tell, the Americanization of Japan is everywhere in Stray Dog and it fits awkwardly, like someone else’s shoes.

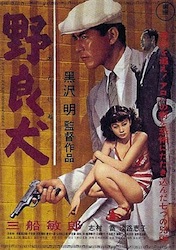

It is the story of Murakami (the always powerful Toshiro Mifune, hot from the success of Roshomon the year before) a young former soldier turned homicide detective whose police-issue pistol is stolen and used to commit crimes. Murakami searches frantically throughout the underside of Tokyo for his missing gun.

It is the story of Murakami (the always powerful Toshiro Mifune, hot from the success of Roshomon the year before) a young former soldier turned homicide detective whose police-issue pistol is stolen and used to commit crimes. Murakami searches frantically throughout the underside of Tokyo for his missing gun.

The first time I saw Stray Dog I thought that Murakami was making a bit too much of the problem. But then, I have always lived in a society where all manner of guns are pretty commonplace. A policeman in Los Angeles losing a gun would be a significant concern, and I’m sure an investigation and disciplinary action would follow. But Murakami goes further than I believe modern police would go, putting everything on the line to get the gun back.

Throughout the film, Murakami is the quintessence of single-minded determination and responsibility, contrasted constantly with a jaded, beaten-down and often ambivalent society. Much of the film involves a sweaty, intense Murakami and, later, Sato (a more calm and seasoned detective, played Kurosawa regular Takashi Shimura) running all over the joint looking for the missing piece. Okay, I am seriously simplifying things, here. The film’s success as a detective thriller doesn’t come from having a hugely complicated plot, though. It works because it communicates—through the power of the actors and a mix of stock footage and gorgeous shadowy cinematography—the compulsion to find something terribly elusive.

The general citizenry in post-war Tokyo didn’t have easy access to handguns. And crime was rampant. The war impoverished the entire country. A gun in the hands of a criminal is always serious, but all the more so when the populace is desperate.

But there is more to it than the criminal element. In understanding Murakami’s obsession with finding the gun, I think we have to look at the martial history of Japan, and in so doing we see what I believe Stray Dog is really about.

Japan’s relationship with the west vacillated between long periods of isolation and shorter periods of openness and trade after which they’d slam the door shut all over again. The Portuguese brought Christianity and guns in the 16th century, and those guns played a major role toward the end of the Warring States period due to pro-gun, pro-Christian warlord Oda Nobunaga. And after that, the Portugeuse got the boot once more, and western things were shunned. Christianity was persecuted and driven underground. Guns remained but were rare.

Under the Meiji Restoration of the mid-19th century, Japan became very pro-Europe and pro-industrialization until the new industry caused a swelling of military power and aggression, especially against China and Russia. This aggression soured relations with the west, escalating ultimately into the attack on Pearl Harbor.

In Kurosawa’s samurai films, there is an unmistakable contrast between the sword and the gun. The sword is art, finesse, martial beauty and brutality at once. The gun is a sleazy expedient, favored by criminals. It’s cheating, basically, and has no place in the samurai ethic.

Imagine if Stray Dog had been set in 1549 instead. Imagine if Mifune had played a samurai who had lost his sword. It would seem perfectly right and reasonable for him to spare no effort in finding it. But a gun is not a sword. Not in the west and certainly not in Japan. In Stray Dog the gun is vitally important to Murakami. I think that part of what drives Murakami so crazy is that he is treating this nasty American piece of non-Bushido as if it were a sword. But Murakami is a soldier from a failed war, not a samurai. And Japan itself is just as lost as the gun, its sense of military power and glory destroyed, its culture buried in an avalanche of American occupation.

Imagine if Stray Dog had been set in 1549 instead. Imagine if Mifune had played a samurai who had lost his sword. It would seem perfectly right and reasonable for him to spare no effort in finding it. But a gun is not a sword. Not in the west and certainly not in Japan. In Stray Dog the gun is vitally important to Murakami. I think that part of what drives Murakami so crazy is that he is treating this nasty American piece of non-Bushido as if it were a sword. But Murakami is a soldier from a failed war, not a samurai. And Japan itself is just as lost as the gun, its sense of military power and glory destroyed, its culture buried in an avalanche of American occupation.

The title covers it all. The stray dog, hungry, dangerous and lost, is the gun, the cop and the culture all at once.

Jason Henninger works for a Buddhist publication in Santa Monica, CA and is happy to be writing for Tor.com again. It has been a while!