Welcome back to Reading the Weird, in which we get girl cooties all over weird fiction, cosmic horror, and Lovecraftiana—from its historical roots through its most recent branches.

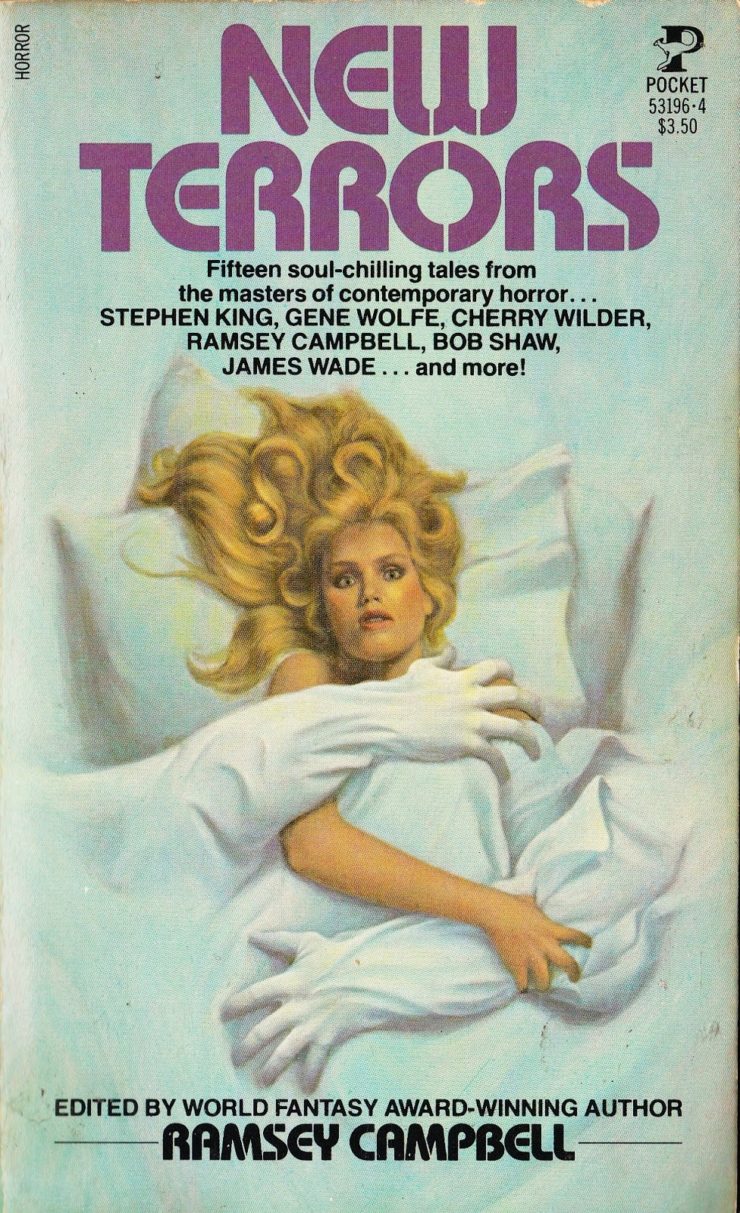

This week, we’re reading Robert Aickman’s “The Stains,” first published in Ramsey Campbell’s 1980 New Terrors anthology. Spoilers ahead.

“For these moments, it had been as if he still belonged to the human race, to the mass of mankind.”

Stephen Hooper has lost his wife Elizabeth to a long illness. On leave from the civil service, he visits his brother Harewood, a rural parish minister and “modestly famous” authority on lichens. To avoid jumpy, domineering sister-in-law Harriet, Stephen roams the neighboring moorlands. His favorite path leads to Burton’s Clough, an isolated little valley.

One day he sees a girl in the hollow. With her grey-green eyes and auburn hair, she seems “part of nature.” She’s collecting lichenous rocks for her father, but knows nothing of Harewood. No, she says, and her father’s no lichen authority. The girl, Nell, agrees to guide Stephen to a nearby spring the next afternoon.

Next day, to Stephen’s jest about her “magic” spring, Nell replies it’s merely very clear and deep. Hiking there, Stephen learns her father is a “cold mortal” who can’t read, for he has no eyes–but has other ways of knowing than books.

Stephen delights in the lustrous pool, imagining it as the source of all Britain’s rivers, pre-pollution. Above it, he sees one of the ruined stone houses that dot the moors. Though Nell claims it’s been unoccupied for centuries, they find modern furniture and upstairs a handsomely carved bed. Stephen hints at living on the moors, and Nell suggests they stay here for the duration of his leave. Stephen considers logistics, then asks what happens if he falls in love with Nell?

Then, Nell replies, he wouldn’t have to return to London.

Stephen asks: would she visit him every day? Perhaps not. If Nell’s father learns about Stephen, he’ll keep her home. He has frightening powers.

Regardless, Stephen returns upstairs with Nell. There her naked perfection ravishes him–but there’s a grey-blue blotch above her right breast, both disturbing and appealing. Nell’s wild plunge into lovemaking renders Stephen breathless–she’s like a maenad, a raving follower of Bacchus; or an oread, nymph of the mountains. She’s “more wonderful than the dream of death.” She can’t possibly exist.

Stephen says tomorrow they’ll settle in together. Nell hesitates. Her father may interfere, because he can read minds. But Stephen’s determined. They’ll stay on the moor, then go to London. As they leave, Stephen notices lichens and moss coating the house inside and out.

Back at the rectory, Harriet’s been taken to hospital, prognosis grim. Though he should stay with Harewood, Stephen’s compelled to return to Nell. That night he notices a new blotch over his bed. He dreams of Nell giving him water from a blemished chalice and wakes strangely thirsty.

Buy the Book

Night of the Mannequins

For the next fortnight, Stephen and Nell share an intense idyll, punctuated by Nell’s baths, sunk in the spring’s pellucid water. To supplement Stephen’s provisions, she gathers wild foods. Her blemish shrinks, even as the house growths burgeon.

Leave over, Stephen takes Nell to the London flat he shared with Elizabeth. Waiting there is a book obviously meant for Harewood: Lichen, Moss, and Wrack. Usage and Abusage in Peace and War. In the guest bedroom, marks “like huge inhuman faces” have appeared on the walls.

At Stephen’s office, his senior remarks he looks “a bit peaked.” Before their usual swim, a colleague points out a mark on Stephen’s back, “the sort of thing you occasionally see on trees.” Stephen avoids examining the “thing.” Back home he notices growths in the sitting room like the tendrils of a Portuguese man-o’-war. Sex takes his mind off unpleasant “secondary matters.” Nell somehow continues to forage. The flat continues to deteriorate. Never mind, as soon as Stephen finalizes his retirement, they’ll return to the moors.

At the moor house, “secondary matters” include accelerated lichen growth, the disappearance of Nell’s mark, and the appearance on Stephen’s hands of “horrid subfusc smears.” Sex that night is “nonpareil,” until Stephen hears the music Elizabeth preferred for lovemaking and sees her ghostly portrait on the wall. Outside there’s persistent animal snuffling. Nell curls up sobbing; Stephen intuits the snuffler is her father. What now?

They must hide. Downstairs, Nell lifts a stone slab from the floor, revealing a coffer-tight room and the stifling smell of lichen. There’s a ventilation pipe, Nell whispers, but “he” may come through it. Moments later, she reports, “He’s directly above us.” The two have time to exchange declarations of love, and then….

When Stephen’s body is finally found by the spring, “the creatures and forces of the air and of the moor” have left no ordinary skin. Cause of death remains open. During the funeral, Harewood notices unidentifiable lichen on the coffin and in the grave. Later he finds Stephen’s flat a shocking mess. Sadly the book on lichen must be sold to benefit the estate.

What’s Cyclopean: Stephen claims to have reached the “male climacteric,” playing on an obscure term for menopause (women get hot flashes, men get fungal growths). He also searches for a “decisive declivity” on his hike, and there are “uncovenanted blemishes” on the car.

The Degenerate Dutch: Only supporting characters with no speaking role have ethnicities (Stephen’s new post-Elizabeth servant is half-Sudanese, a doctor never consulted is West Bengali, and the girl in the typing area is “coloured”); the more prominent characters remain unmarked (so to speak). Also foreign food, and foreign-ish food made by British folk, is extremely suspicious. Mashed turnip with mixed peppers reflects Harriet’s love of “all things oriental.” Harriet plans rissoles sautéed in ghee, but both Stephen and Harewood apparently find clarified butter deeply intimidating. These people would faint in the produce section of Whole Foods.

The “controversies about South Africa” that Stephen considers “fashionable church preoccupations,” and that Harewood doesn’t care about, refer to apartheid.

Weirdbuilding: Lichen is, after all, merely the result of a mutualistic relationship between algae and fungi. The mushrooms are out to get us, always.

Libronomicon: Stephen is upset to receive a tome ostensibly meant for his brother: Lichen, Moss, and Wrack. Usage and Abusage in Peace and War. A Military and Medical Abstract. Perhaps it has some bearing on his situation. Stephen also keeps forgetting that Nell is “unaccustomed to book metaphors” and suspects that his own ability to read will fade in her presence—he seems to welcome this, as he welcomes the other simplicities of their life together.

Madness Takes Its Toll: Denial is neither a river in Egypt nor a useful treatment for lichen infestations.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

Aickman talked in his World Fantasy Award speech about having reverence for things one cannot understand. Which I do, but there’s a certain level of not-understanding beyond which a story needs to do something to ensure that my reverence outweighs my frustration. Given that this story won a British Fantasy Award, many people clearly appreciated the things it was doing, and I can see what some of those things are—but my copy is peppered with rather more “???” notes than is my usual wont, and I unfortunately found it less reverence-inducing and more unsatisfying. Maybe it’s just a bad week for my ability to appreciate the irrational.

Part of my dissatisfaction stems from the story’s treatment of its women, who are deeply symbolic but can totally be counted on to cook and do the dishes. Elizabeth is vaguely saintly—I’m not clear how she did the dishes while wasting away, but Stephen certainly doesn’t think of it as his area of competence (perhaps it was the province of the now-departed servant). Nell is a wandering nymph, a sacred innocent who “could not possibly exist” but is supernaturally good at housekeeping. Harriet is neurotic and annoying, the better to contrast with Nell and Elizabeth, vaguely detestable but still leaving a doing-the-dishes-shaped hole in her husband’s life when she suffers a stroke. Improbable innocence should not be a prod to love at first sight, and women are not weird magical incursions into the realities of male life. It’s hard to appreciate the numinousness of it all while wishing for several of the numinous things to get more sharply detailed characterization.

Where the story gets interesting—and I suspect this is what appeals more to other readers—is in the lichen itself. Or rather, Stephen’s response to it: it becomes apparent as the story goes along that he, not Nell, may possibly be the one carrying the contagion. He implies strongly that the lichen problem in his original house predates Elizabeth’s death, and describes her as “disintegrating,” which could be intended poetically only maybe not. He sees Nell’s innocence as “life or death,” and tries to keep from noticing both his own spreading stains and the passage of time, as if he can stop both by denying both. There are suggestions that his life with Elizabeth wasn’t entirely ordinary either—she tended to faint at “the sudden presence of the occult.”

Then again, time’s going strange, so reports of life pre-Nell may not be entirely accurate. Or Nell’s own contagion may not be time-bound.

Some of this is perhaps autobiographical, given that the story came out shortly after Aickman was himself diagnosed with cancer that he refused to have conventionally treated. The power (or lack thereof) of denial, and the fear of the consequences of noticing reality, are the most compelling things here. And it’s not clear what ultimately kills Stephen—is it, in fact, Nell’s terrifying and unseen father? Or is it his own lichen infestation, carried with him into their hideout? Or does Nell’s attempt to run away from her inescapable parent mix in some unknown and deadly way with Stephen’s attempt to run away from reality?

Mortality holds a strange place in the weird, both universal and incomprehensible, crusted with human meaning but the ultimate reminder that the world does not revolve around our existences. Lovecraft’s late stories play with the idea of legacy and immortality at great cost; other writers have shown us terrifying and enticing deaths and avoidances thereof. Stephen’s lichen feels more like a hound of Tindalos, its inevitability and the desperate attempt at denial driving the story more than its actual form. Not to whine about the ultimately triviality of human life, but I would have been happier if his remorseless fate had a little more definition.

Anne’s Commentary

Robert Fordyce Aickman (1914-1981) was a society junkie, it appears. A dedicated conservationist, he co-founded the Inland Waterways Association, which was responsible for the preservation of England’s canal system. He was also the chairman of the London Opera Society and a member of the Society for Psychical Research and the Ghost Club. That’s naming just a few of his affiliations and, by clear inference, his wide-ranging interests. Fortunately for lovers of weird fiction, he still had time to write forty-eight “strange stories,” as he liked to call them.

Are his stories strange? Hell yeah. My own reaction to Aickman is often, “Whoa, what just happened here?” And “Is this really the end of the story?” And, “Robert, you tease, come back! Tell me more! Explanations, please!”

In an essay Aickman wrote after receiving the World Fantasy Award for “Pages from a Young Girl’s Journal,” he addresses my concerns, and those of many other readers presumably:

“I believe in what the Germans term Ehrfurcht: reverence for things one cannot understand. Faust’s error was an aspiration to understand, and therefore master, things which, by God or by nature, are set beyond the human compass. He could only achieve this at the cost of making the achievement pointless. Once again, it is exactly what modern man has done.”

I’ll admit it, sometimes I do get all Faustian, wanting to penetrate the glamorous obscurity of stuff “set beyond the human compass.” But I can also do the Ehrfurcht thing. Ehrfurcht is an interesting word. In addition to “reverence,” it can translate to “respect” and “veneration.” Fine, those words are close relatives. Ehrfurcht, however, can also translate to “fear,” “dread,” “awe.” On first consideration, those two sets of words look like antonyms. On further consideration, aren’t those who revere God often called “God-fearing?” Isn’t “awe” an emotional state so intense it can readily pass from pleasure to pain?

In this blog we’ve often explored the psychological phenomenon of fear coupled with fascination. By now it’s our old friend, and as with actual old friends, we can endure (or even come to embrace) some seeming contradictions. We don’t necessarily have to understand in order to appreciate.

Many years ago I cross-stitched a sampler that echoes Aickman’s credo. Its motto is: “While the Glory of God may exceed our Comprehension/Our Endeavor must be that it does not exceed our Appreciation.” Surrounding these Words of Wisdom are rose bowers and ecstatic bluebirds. How’s that for a mysterious Meeting of Minds? Maybe minus the roses and ecstatic bluebirds, although “The Stains” does feature a lush flora of lichens and mosses and those maybe-kites that (ecstatically?) fly round and round Stephen’s moor house at all hours.

I don’t understand “The Stains.” What exactly is Nell, maenad or oread or some less classical elemental? What is that wonderful, frightening, eyeless, snuffling Father of hers? What about that variably-named Sister? Is Nell a vampire of sorts–Stephen’s intimacy with her leaves him like death warmed up. Is Harriet a vampire of sorts–Harewood gets over his chronic ailments once she’s gone. How about Elizabeth? Her long decline was, unavoidably, a heavy drain on Stephen’s energy and emotions. But what was their relationship like before? Stephen’s idealization of Elizabeth smacks to me of a protest-too-much. He credits her with making civil-service life tolerable; but might it not be she who first tied him to that life? Oh, the mundanity! Whereas Nell is celestial, an impossible creature, more wonderful than the dream of death.

Pause it, Stephen. Are you just waxing Romantic, or do you really find the dream of death wonderful? If the latter, do you mean by wonderful a consummation devoutly to be wished or do you mean that death as a concept is full of wonders?

What about those vegetal elephants-in-the-story, the staining lichens and mosses that pervade everything in Stephen’s vicinity once he connects with Nell? Do Nell and her kin spontaneously generate these growths? Do they infect human associates with a similar contagiousness? Are they to be seen strictly as agents of destruction and decay? Or as agents of transformation?

What’s with Stephen’s conviction that he must change the nature of time to remain in the alternate reality Nell represents? The clock-time of bureaucracy was his master. He finally masters time through perfect union with Nell–Time loses its power.

Without time is there life as mortals know it? Do Nell and her “cold mortal” Father understand mortality as Stephen does? Does the tramp’s discovery of Stephen’s remains mean Stephen’s truly dead? Or has he suffered a moor-change?

I don’t understand “The Stains.” I don’t have to in order to appreciate it. In this late-career story, Aickman is master of his “trademarks,” the (M.R.) Jamesian authority of language and voice; the richness of detail and imagery; the deft sketching of worlds intertwined with our surface reality; the imagination-stirring ambiguity of creatures glimpsed lurking in shadow or flashing by in unbearable light. Does he understand his own tales?

On some level below or above or beyond the niggling rational, I think he does, and I think we can, too.

Next week, we take a break along with much of Tor.com to focus on/be anxious about the election and the cosmic horror potential of current events. Go forth and vote: sometimes ramming Cthulhu makes a difference. We’ll be back in two weeks, whatever reality looks like by then, with Chapter 3 of The Haunting of Hill House.

Ruthanna Emrys is the author of the Innsmouth Legacy series, including Winter Tide and Deep Roots. Her short story collection, Imperfect Commentaries, is now available from Lethe Press. You can find some of her fiction, weird and otherwise, on Tor.com, most recently “The Word of Flesh and Soul.” Ruthanna is online on Twitter and Patreon, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her young adult Mythos novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.