One of the great traditions of science fiction has been the imagining of planets far beyond our own solar system. Authors and filmmakers allowed their imaginations to run wild, bringing us exotic topographies, twin suns, and the occasional terrifying mountain of water. It’s easy to forget that it wasn’t until 1988 that we discovered our first factual exoplanet. We’ve done some serious catching up since then: last month NASA dropped the science that, after a massive Kepler haul of 715 previously unknown planets, we are now aware of 1,771 exoplanets. (at least two of which actually meet our sci-fi expectations.

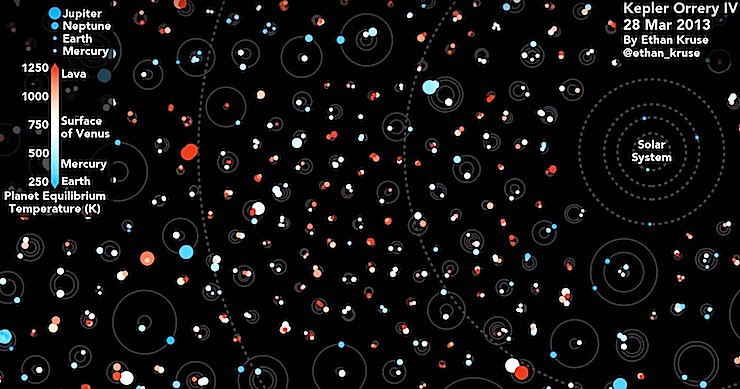

Since most of these planets are too far away to be seen, a helpful animator named astrocubs has created a gorgeous animation to approximate their orbits.

Looks like a bunch of atoms with their electrons all fizzing about. Whoa…What If The Whole Universe Is, Like, One Huge Atom?

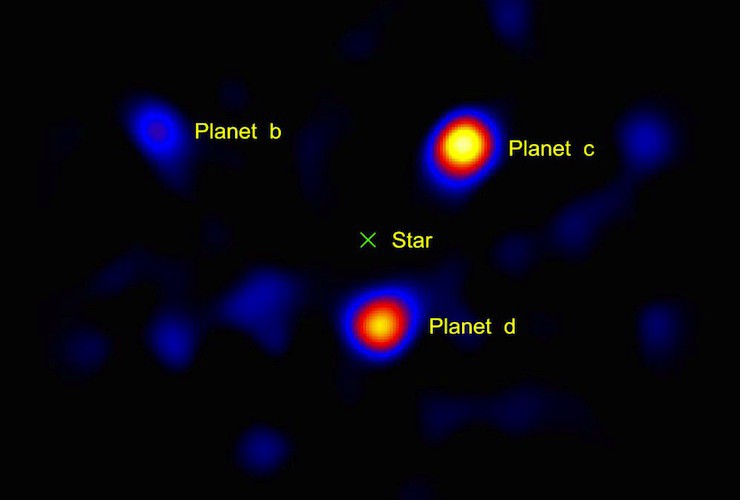

Now, how can we even create an approximation when these planets usually can’t be seen? As this fascinating Smithsonian article discusses, there are four main methods to find an exoplanet you can’t see, using Gravitational Lensing, Radial Velocity, Orbital Brightness, or the Transit Method. Occasionally you get lucky, and the planets are so freaking huge you actually can see them, as is the case with these, shown orbiting the star HR8799 in 2010:

While the animation above isn’t an exact representation of these exoplanets and their movements, it does give us the thrilling sense of just how many worlds are still out there for us to explore.

At least, if any of them want us to.