You’ll have to forgive me for titling this particular reread with a Robot Chicken quote—it seems appropriate, given the polarizing effect Boba Fett’s Expanded Universe resurrection has on Star Wars fandom. Personally (very, very personally, since I’ve adored Fett since I was a kid), I don’t understand why anyone has a problem with it. His death was poorly conceived to make a bad joke during a great big fight sequence. If writers want to resurrect him, they should. They really, really, should.

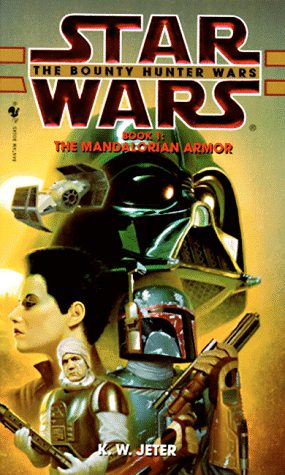

Also, The Bounty Hunter Wars Trilogy by K. W. Jeter were some of my favorite Star Wars books growing up. So I have lots of feelings where Boba Fett is concerned, and tend to gloss over the complaints. You can’t win with Star Wars anyway—fans want to change all sorts of things about the films, but when Fett blows up the Sarlaac in a novel it becomes “fan pandering.” It’s not worth keeping straight.

One aspect that makes this trilogy stand out is the narrative structure; the books are split between the present (set during Return of the Jedi) and the past (between A New Hope and Empire Strikes Back). In the present, Dengar is helping Fett to convalesce after he and his betrothed Manaroo find the bounty hunter’s ravaged body beside what remains of the Pit of Carkoon. There’s a woman from Jabba’s palace who insists on checking in with Dengar on Fett’s progress; she has amnesia and used to be a dancing girl, but she knows that isn’t who she really is. And she knows that Fett can answer all her questions. While all that is going down, Kuat of Kuat, the practical CEO of Kuat Drive Yards (who makes most of the big, pretty ships in the Star Wars universe) is dropping bombs on them and trying to blur Fett out of the picture. Why? Well, you can’t very well find out now, can you?

Most of the fun in the present sections come from getting to learn more about Fett by seeing him at his most vulnerable—how he handles himself when he’s barely capable of standing is part of what makes him compelling. He’s still handing out orders to Dengar, still pole-vaulting his way out of impossible situations, still incapable of calling it quits when he really should just be happy to take a nap and giggle hysterically in his sleep over having survived. And his… I’m going to call it “situational loyalty” to Dengar and Neelah is a staggering quality when it’s set opposite the flashbacks….

The sections set in the past are primarily concerned with a job given to Fett by Prince Xizor, head of the Black Sun—to destroy the Bounty Hunters’ Guild from the inside-out. Xizor’s reasons for this are explained to the Emperor and Vader—what the Empire lacks is specialists. There’s too much homogeny, and so a group of highly-trained bounty hunters could easily be of use to the Imperials, provided that they can wreck their union and skim the best off the top of the bounty barrel. Fett is only too happy to get the assignment; the Bounty Hunters’ Guild has been so many squashed bugs on his windshield, annoying and inconveniencing him, but never posing any actual threat to his business model. He thinks they’re all a bunch of incompetent dingbats (ding-mynocks?). He’s not wrong.

What’s bemusing is how little Fett has to work to bring about the Guild’s timely end. All it really takes is one big, bad job; he gets Bossk, Zuckuss, and an old friend named D’harhan to help him on a team bounty, nabbing a guy from the Shell Hutts. If you’re wondering what Shell Hutts are, well… they are Hutts who realized that they had certain bodily weaknesses and elected to encase themselves in, um, shells. It turns out that their leader, Gheeta, already knew what the hunters were after and has designs on all their lives because Fett stole a very talented architect from him a while back. (Which is just a perfect illustration of how petty Hutts can be; the exact same sort of revenge complex that got Han Solo tacked to a wall for half-a-year or so.) In order to get out alive, Fett has to sacrifice the only person on the mission he cares about at all—D’harhan.

In the meantime, Bossk’s journey from entitled brat son to extra-entitled brat would-be leader is just beginning: when they all get back, he decides it’s time to kill dear old dad Cradossk and effectively splits the Guild in twain with that single action. Just one bad experience with Boba Fett was all it took. Clearly, Fett should make a point of actively irritating other bounty hunters more often. He probably would if more people paid him to do it.

Another figure at the center of this strange tale is the Assembler, Kud’ar Mub’at, a galactic go-between who delivers bounty cargo for a small percentage. Living out in space inhabiting something that resembles a giant web, the Assembler has a life-cycle, in a manner of speaking. As a sentient computer of sorts, it has nodes that do parts of it’s work, the simple bookkeeping and such—eventually one of those nodes inevitably gets too bright for its britches and takes down the head node, thus becoming the next Assembler. Kud’ar Mub’at acts very comfortable in his position for the time being, but that seems likely to change… also no hardship for Fett since Mub’at’s extreme sycophancy and prying questions make business a trial to get through.

The Star Wars galaxy as it appears on film is a place of colors in stark contrasts—the blacks and whites especially. The protagonists are sometimes too good for their own good. What stories like these offer are a chance to wade around in the muck. It really is saying something when you can point to Boba Fett as the most morally aligned individual in your story, but it makes for as much humor as it does drama. Zuckuss, in particular, has the rough job of playing the sensible coward opposite everyone else’s growls and heel-snapping, and you sort of want to hug him for it.

For the record: the plots of these books are stupendously complicated. There are plots within plots beside plots cuddling up to other plots half-a-galaxy away. How they pan out is a discussion for the later books, but the first novel leaves us with lots of intriguing questions, which is exactly what it needs to do. Who is Neelah? What does Xizor really have invested in all this? Why does Kuat of Kuat need Fett killed?

There are little bits here and there that go against Fett’s stories in the Tales of anthologies, but overall, everything plays together nicely. It’s exciting because these books were the place where the overall idea of Fett’s character coalesced in the Expanded Universe. What emerges is something of a lone cowboy archetype; he’s silent, deadly, stuck on his own sense of justice, uncompromising, sarcastic, and possessed of an odd soft spot that peeks out when you least expect it.

It made a three-line character with a cool costume into something of a legend in his own right. For those who wish Fett had stayed in the Sarlaac’s belly, it was never going to play. For those who had been desperate for more tales about that stoic guy in Mandalorian armor… well, I stayed up well past lights-out to find out what was coming next.

Emmet Asher-Perrin really did stay up with the light on forever to figure out what was going to happen poor D’harhan. She has written essays for the newly released Doctor Who and Race and Queers Dig Time Lords. You can bug her on Twitter and read more of her work here and elsewhere.

I haven’t read these, but I kinda want to now, especially hearing about the amnesiac dancing girl(Hi, Mara!!!! I miss you!!!)

Fett’s “resurrection” didn’t bother me; he never actually died (remember that the Sarlac “digests its victims slowly, over the course of a thousand years”). Pre-special editions, the thing didn’t even have jaws, so it was clearly relying on its digestive juices to liquify its prey, like a pitcher-plant.

Given that Fett was wearing full armour (and still had his weapons) when he went in, it seems obvious that he’d be able to survive at least long enough to reach his explosives.

I wish I could remember why I hated these books so much.

As stupid as Fett’s original death was, I believe his return happened around the same time the Emporer was reborn in Dark Empire, so it seemed excessive to bring back two characters thought to be dead.

Yeah, I was into Boba Fett as a teen too, and so where there may be some legitmate stylistic reasons to oppose bringing back Boba Fett (kind of how it REALLY irritates me that they brought back Darth Maul in the Clone Wars) simply because he is a ‘cool character’, at the time I just thought it was awesome (along with the Emperor’s resurrenction in Dark Empire). But I do agree that out of all of the resurrections, Fett’s does at least make some sense without a ton of retconning or needing to provide some kind of backstory/explanation/technology that’s not immediately obvious from the movies – it’s not terribly unreasonable to assume that, with Fett’s technology and weapons, he could escape from the pit.

Anyway, I am SO enjoying these re-reads. I actually don’t remember all the details about what went on in these books, so now I’m kind of wondernig what happens!

Also, I live in Wisconsin so it’s kind of funny to realize that the Empire is in to union busting ;) (Insert Imperial Walker joke here)

It’s been ages since I read these books, but I remember really enjoying them. Now I want to go back and read them again!

Oh these were some of my favorites!! Just reading this made me feel all warm and nostalgic. Thanks Emily.

I also have Fett’s voice from Robot Chicken in my head now…haha, just love that sequence. Thanks for the fun reminder – much enjoyed this article!!

Boba Fett’s voice on Robot Chicken is done by Breckin Meyer, and it’s perfect.

Funny story – when I was in middle school I had a HUGE crush on Breckin Meyer (from Clueless). It was in 8th grade that I got really into Star Wars. A few months later, there was a short blurb about him in Seventeen (yes, I got that magazine, don’t judge!) and how he was this huge Star Wars fanatic and collected action figures – it had a picture of him with his collection. SWOON. The article also made this offhand mention of how he and his friends would make their own or modify them, which I can’t help but wonder is a prediction of his Robot Chicken days.

Anyway….I love the Robot Chicken specials so much, and I love that Breckin Meyer is on them, haha. My husband and I quote them to each other ALL the time. We actually bought the Hallmark Bossk ornament last year because of the Robot Chicken skit, haha. Good manners are their own reward!

Actually, I find it kind of hard to watch the movies with a straight face now :)

If Derek Jeter played baseball like K.W. Jeter writes fiction then the Yankiees never would have won all those World Series in the late 90s! I use that analogy because as Derek Jeter was having his best years with the Yankees, K.W. Jeter was writing some of the worst Star Wars novels I have ever read. In my opinion the mid and late 90s was the golden age of EU Star Wars novels and stories and we were treated to the amazing X-Wing novels, Zahn’s novels, A.C. Crispin’s interesting take on the origin or Han Solo and more…then the Bounty Hunter Wars came out. Talk about a road apple amongst the gems! Awesome concept that could have been so action packed and full of Star Wars adventure and cool. However, the carry through was dry and boring and full of pointless mental introspection and all flashbacky and there was some kind of alient monster thingy POV and…UUUUUUGGGGGGG!

Save yourselves disappointment and mental anguish and read The Tales of the Bounty Hunters if you want Star Wars EU bounty hunter cool and fun. I don’t know what it is about EU writers when Bobba Fett is the POV character but got they write boring boring boring junk with a character who is an action hero!