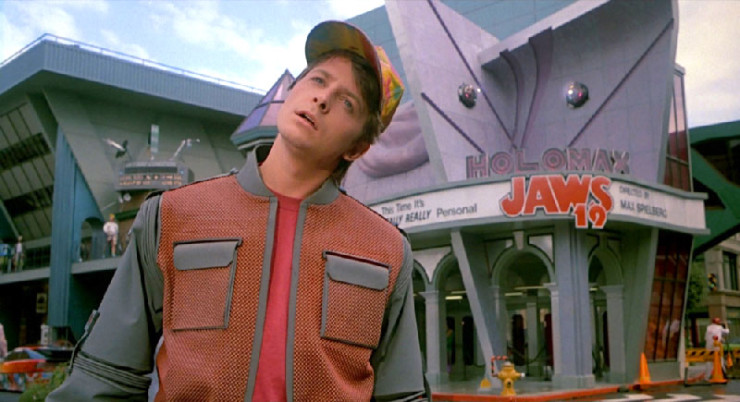

The giant, computer-generated, holographic shark looms out from over the theater marquee advertising Jaws 19. It bears down on an unsuspecting Marty McFly, the teenage visitor from 1985, recently transported via DeLorean time machine to the FAR FUTURE! of 2015 Hill Valley, CA. Too late, Marty realizes that he has been targeted. Turning to behold the monster, he screams and cowers, only to discover the cavernous maw dissipating just before it swallows him whole. Once the illusion has vanished, he gathers his wits, and mutters dismissively: “Shark still looks fake.”

The gag, from early in Back to the Future Part II (1989), is clearly director Robert Zemeckis’ gentle dig at Steven Spielberg, whose Amblin production company produced Part II (as well as its 1985 predecessor, and the eventual Back to the Future Part III the following year), and whose travails with the notoriously malfunctioning Bruce the Shark on the original Jaws (1975) have been well-documented. But it’s also something more: A slap at the film industry’s seemingly insatiable hunger to milk a hit unto exhaustion, in this case by taking the water-bound thriller helmed by Spielberg—which had become the poster child for the phenomenon known as sequelitis—and conjecture that by the time we were well into the 21st century, the franchise would have been releasing a new chapter approximately every two years.

Zemeckis doesn’t end the critique there, though. It extends into the whole first act of Part II. When we last saw Marty McFly (Michael J. Fox), and his girlfriend Jennifer (Claudia Wells) in the original Back to the Future (1985), they were being whisked thirty years hence by Doc Brown (Christopher Lloyd) in order to save their yet-to-be-born progeny from some dire-but-undefined fate. It apparently wasn’t Zemeckis’ and co-writer Bob Gale’s intent for that tag to be the launching point for a follow-up film, but any audience member of the time who had grown accustomed to how Hollywood was cranking out sequels—essentially by taking the same plot, amplifying some of the more popular bits, throwing in a few twists, and shoveling it out into theaters—could easily walk away from that finale anticipating what would come next: Another chapter, mirroring the beats of the original film, but taking place in… THE FUTURE!!!!! (Okay, I’ll stop.)

But four years had passed between parts one and two, and in the interim, Zemeckis had helmed another massive hit, one even more technically advanced while being unbeholden to any previously released movie: Who Framed Roger Rabbit. By the time the director got back to pondering the further adventures of Doc and Marty, it seems he and Gale were not eager to just throw a handful of robots into the Recyclotron and call it a day. Instead, Zemeckis would rely on his talent for leveraging filmic techniques and special effects to create something that doubled down on BTTF’s time-travel concepts while also deconstructing the whole notion of the commercial sequel. (Note: I tried reaching out to both Zemeckis and Gale to better understand how they arrived at what would become Part II. Zemeckis’ rep said he was not available; Gale’s rep did not respond.)

That seeming reluctance to just future-date a regurgitation of the first film may explain how act one of Back to the Future Part II wound up the way it did. To be delicate about it, the 2015 section is… not good. The pacing feels off, the characters are painfully broad, the hoverboard chase sequence is poorly staged. Crispin Glover, the original George McFly, is ubiquitous by his absence (no, hanging his stand-in upside down is not an adequate substitute), and Jennifer for some reason is shunted to the side, despite the fact that actress Elizabeth Shue, replacing Wells, handles the few moments she is given better than most of the rest of the cast. It’s as if Zemeckis and Gale were rushing to clear the table they had inadvertently set in ’85, just so they could get to one, pivotal moment, when an aged and embittered Biff Tannen (Thomas F. Wilson) absconds into the past with a sports almanac. Whether or not Zemeckis’ intent was to expose the hollowness at the heart of most sequels, act one is an unsatisfying sequence that, mercifully, is over quickly enough.

Things get onto a firmer footing once Marty and Doc (and Jennifer. Almost forgot about her. Hi, Jennifer!) get back to 1985. Well… firmer footing with the exception of the way that Marty discovers that the “present” he’s returned to is neither the one he left at the end of the first movie, nor the less-desirable one he was enduring at that film’s beginning. On paper, having him barge in on an African American family living in what used to be his home may have looked like the fastest and funniest route to getting a point across; on-screen, it does not play well—especially given the father’s hyperbolic, baseball bat-flailing reaction to Marty’s intrusion. What little saving grace there is comes in something the father cries as Marty flees, something that likely eluded the attention of most audiences amidst all the chaos: “You tell that realty company that I ain’t selling. We ain’t going to be terrorized.” From the director whose Who Framed Roger Rabbit was all about systemic racism—particularly in how underprivileged communities are sacrificed on the altar of commercial interests—it’s a pretty clear sign that, while Zemeckis may have miscalculated whether the comic impact in this sequence was worth the uncomfortable imagery, his empathies are in the right place.

Clear of that ill-advised moment (which is followed by a much better scene featuring James Tolkan’s Principal Strickland done up in full Rambo/Mad Max regalia—and probably enjoying this dystopia more than anyone should), Zemeckis finally shows his hand, not only carrying forward his treatise on sequels, but also providing a different kind of time-travel story, one that looks into his own future.

In the second act, set in a third iteration of 1985 Hill Valley, Marty has to contend with what his hometown has become once Old Biff has delivered the sports almanac to the Young Biff of 1955. Turns out the teen lunkhead has taken full advantage of the book, gambling himself into an ungodly fortune that allows him to become a titan of (environmentally calamitous) industry, while also taking the opportunity to kill George McFly, marry a surgically enhanced Lorraine McFly (Lea Thompson), turn the quiet, unassuming Hill Valley into a garish, Vegas-like hellhole, and exile this timeline’s Marty to a school in Switzerland. Zemeckis plays this sequence for all the nightmare fuel it can provide, but if you watch closely, you might realize that there’s something distinctive in the specific way the horror show plays out.

It would be noted that two films hence, after Back to the Future Part III (which was filmed back-to-back with Part II) and Death Becomes Her (1992), Zemeckis’ choice of subject matter would undergo a profound evolution. With the release of Forrest Gump (1994), he would abandon broad comedy for something more modulated. Instead of snarky heroes, Gump’s protagonist—in a marked departure from the original novel—would be a sweet innocent, set at odds with the cold, harsh society the rest of us must contend with. The word “Capraesque” would frequently be applied to the film, referencing director Frank Capra, who, in such films as Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939) and Meet John Doe (1941), also presented portraits of simple, honest souls pitted against the cynicism of those around him.

But no one remarking on Zemeckis’ embrace of a legendary director should have been surprised—it was already there in Back to the Future Part II, whose second act leans heavily on the Capra playbook, and on one film in particular: It’s a Wonderful Life (1946). In that title’s best-remembered sequence (so much so that it became a staple—maybe the better word would be “hackneyed”—TV plot device), the guardian angel Clarence (Henry Travers) gives beleaguered and suicidal banker George Bailey (James Stewart) a glimpse of what the world would have been like had the earnest businessman never been born.

Capra does not spare the audience anything in this unrelentingly dark vision, laying out an unyielding string of death and disaster, all because Bailey was not around to intervene. The climax of the sequence has George taking a tour of the little town formerly known as Bedford Falls, NY—now redubbed Pottersville in honor of the ruthless robber baron who has taken control—and discovering what a lurid mess it has become. And while four decades of technical achievement have changed the way an urban disaster area can be portrayed on-screen, BTTF2’s overall impact as Marty discovers the depths to which Hill Valley has descended is pretty much the same, as is Zemeckis’ willingness to take the audience deeper and deeper into an unrelenting nightmare, climaxing with Marty collapsing in tears over his father’s grave.

In another nod to Capra, Zemeckis gives Marty his own guardian angel, in the person of Doc Brown. Except instead of divine intervention, the Doc brings scientific explanation, with a mapping out of how Biff’s meddling has split Marty and Doc (and Jennifer—we love you, Jennifer!) off from their original timelines into this accursed one. And with that, and a little bit of chase sequence action to keep things lively, Zemeckis steers the film into its final, and trickiest act (and I can’t be the first to think that this final part should be called Back to Back to the Future).

If the first act appears to be Zemeckis giving the stink-eye to the whole just-do-it-all-again-with-variations concept of sequels, act three has him going, “Okay, you want the same thing? We’ll give you the same thing… literally.” The film’s last and longest segment is a virtual replication of Back to the Future’s finale, with a new story intricately woven within. So as part one’s Marty continues his mission as extra-terrestrial matchmaker, Part II’s Marty struggles to retrieve the almanac from part one’s Biff, all while avoiding an alteration of the original film’s events or experiencing a paradox-triggering encounter with his other self.

Buy the Book

Emergent Properties

There’s an awesome grace to the way Zemeckis manages this, editing in footage from the original film, carefully staging re-enactments, and throwing in lots of elegantly deployed motion-control for when two iterations of the same character share the screen. (Plus, to carry forward the Who Framed Roger Rabbit influence, both the Mt. Hollywood Tunnel and the voice of Roger himself, Charles Fleischer, have guest appearances.) The outcome is to pull a kind of double-fake on the commercial concept of the sequel, giving the audience, and the execs, exactly what they want, but not really, unfolding the story to reveal another one operating beyond.

And for a column I created to examine how the stories SF films tell help us examine ourselves and our universe, Back to the Future Part II becomes an outlier, of note for what it says about the nature of storytelling itself. A narrative can focus in on one event, but how many others may be playing out, unseen, at the same time? Artists from Tom Stoppard to M. Night Shyamalan to the team-up of Ron Moore and René Echevarria for DS9’s “Trials and Tribble-ations” have experimented with ways to pull the curtain back, revealing to an audience details that they didn’t originally perceive, but that influence and deepen understanding once discovered.

In Zemeckis’ case, the trick gets pulled off on a technical level with skillfully deployed staging, editing, and special effects, and on a conceptual level by taking the analogy of time as a river and finding ways to let the various streams of a narrative flow and intertwine into each other. The scenario that results is both balletic in its complexity and dynamic in its action. If the characters of the original Back to the Future are shaken out of their complacency about the way things are, the viewers of Part II are roused by the notion that one shouldn’t just accept what’s being splashed across the screen as the be-all and end-all of a tale. In breaking himself free of the curse of sequels, Zemeckis also liberates an audience from a bent toward passive consumption. There are stories beyond the stories, Back to the Future Part II suggests, and maybe it’s not a bad thing if people go forward on their own to imagine what those tales might be.

* * *

Hm, I might have to start a new series, In Praise of Fan-Fic. Someday. For now, I’m on the glide path into Back to the Future Part III, and after the difficulties I confronted in deconstructing Part II—it’s essentially three completely different films folded into one—I’m looking forward tackling a more straightforward narrative, one where Marty McFly finds himself contending with the challenges of 19th century Hill Valley. But what did you think of Part II? Do you feel it came together more neatly than I perceived? Were there lessons to be learned beyond a meta-take on sequelitis? You’re invited to add your thoughts to the comment section below. Just keep it sweet, beet—you don’t have the luxury of going back to fix any unfavorable timelines you forge.

Dan Persons has been knocking about the genre media beat for, oh, a good handful of years, now. He’s presently house critic for the radio show Hour of the Wolf on WBAI 99.5FM in New York, and previously was editor of Cinefantastique and Animefantastique, as well as producer of news updates for The Monster Channel. He is also founder of Anime Philadelphia, a program to encourage theatrical screenings of Japanese animation. And you should taste his One Alarm Chili! Wow!