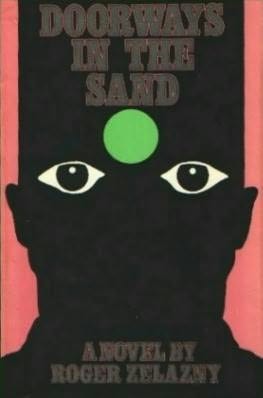

Roger Zelazny was a demented genius who could squeeze words until they sang. I first read Doorways in the Sand when I was thirteen years old. It blew my head off. I’ve read it a couple of times since then, but it isn’t in my frequent rotation, like Isle of the Dead and This Immortal. Like those books, it has a typical Zelazny first-person smartass protagonist, like them it has aliens and shiny SFnal ideas, but unlike them it is written in an experimental way, where almost every chapter starts in the middle and then goes back to get you up to speed just in time for a new chapter and a new reverse-cliffhanger lurch. I didn’t like this when I was thirteen, though I thought it was clever, and I don’t like it now. It seems like grandstanding, and it gets in the way of my enjoyment of the story. It isn’t possible to read the book without spending a lot of time thinking “Huh? How did that happen?” and waiting to find out. It makes it easy to identify with a protagonist who doesn’t know what’s going on either, but it’s irritating. However, the Zelazny I really like is getting too familiar for me to read, so it’s time to turn to the less favourite and therefore still readable.

The too-clever story shaping aside, there’s a lot here to like. There’s the way Zelazny invented this awesome system of education whereby you can take courses in whatever you like, and learn about absolutely everything without ever graduating and getting a degree. He explains it was invented by a Harvard professor called Eliot, in typical science fiction as-you-know-Bob explanation. I was astounded when I found out (too late) that it was real. Fred Cassidy has been a full time student for thirteen years without graduating. He has a hobby of climbing on buildings, which he dignifies with the name acrophilia. He knows quite a lot about a vast range of subjects. By the terms of his uncle’s will, Fred gets a comfortable monthly income until he graduates, so Fred has bent the rules and stayed in school. Meanwhile, we’ve discovered aliens and are part of an alien cultural exchange ring—the Mona Lisa and the Crown Jewels have left Earth in exchange for a very odd machine that reverses stereoisomers and the mysterious Star Stone. The Star Stone goes missing and lots of people and aliens seem to think Fred’s got it. Fred thinks he hasn’t.

Things get weird from there on, but Fred wisecracks his way unflappably through the plot from crisis to crisis, climbing on things from time to time for recreation or escape. It’s a future without technology or social mores having changed much from the mid-seventies when this was written (published 1976) but apart from the way everyone (even the aliens) smokes cigarettes all the time, you almost don’t notice. There’s an alien that disguises itself as a wombat, and another than looks like a Venus flytrap, after all.

In some ways this is like a very simple adventure story. In other ways, it’s like a story of humanity glimpsing the complexities of a galactic civilization. What it’s really like is the stereoisomer of both of those stories, the inverse inside-out twisted version of them. The whole twisted-chapter thing is a meditation on the stereoisomer theme. It really is very clever, and fortunately, very beautiful.

Sunflash, some splash. Darkle. Stardance.

Phaeton’s solid gold cadillac crashed where there was no ear to hear, lay burning, flickered, went out. Like me.

At least, when I woke again it was night and I was a wreck.

Lying there, bound with rawhide straps, spread-eagle, sand and gravel for pillow as well as mattress, dust in my mouth, nose, ears and eyes, dined upon by vermin, thirsty, bruised, hungry and shaking, I reflected on the words of my onetime advisor Doctor Merimee: “You are a living example of the absurdity of things.”

Needless to say his speciality was the novel, French, mid-Twentieth century.

Since this is the beginning of a chapter, you have as much context as any reader for why Fred is tied up, and he doesn’t get around to telling you for pages and pages. If this is going to drive you mad, don’t read this book. If you can bear it, then you have the pretty words and the promise of aliens and a machine with a moebius conveyer belt running through it and the taste of bourbon and fries when you’ve been reversed by the machine. Nobody, but nobody else, could juxtapose all the things in those five little paragraphs and make it all work.

Zelazny could certainly be very odd, and this is a minor work, and not where I’d recommend starting. (That would be with his short stories, presently being reissued in gorgeous editions by NESFA.) But it’s short—I read it in about an hour and a half—and it’s got the inimitable Zelazny voice which will keep singing in my mind when all the details and the irritation have sunk back into oblivion.

There is a man. He is climbing in the dusky daysend air, climbing the high Tower of Cheslerei in a place called Ardel beside a sea with a name he cannot quite pronounce as yet. The sea is as dark as the juice of grapes, bubbling a Chianti and chirascuro fermentation of the light of distant stars and the bent rays of Canis Vibesper, its own primary, now but slightly beneath the horizon, rousing another continent, pursued by the breezes that depart the inland fields to weave their courses among the interconnected balconies, towers, walls and walkways of the city, bearing the smells of the warm land towards its older, colder, companion.

Yup, that’s definitely one of the ways science fiction can make you long to be there. Nobody ever did it better.

Jo Walton is a science fiction and fantasy writer. She’s published eight novels, most recently Half a Crown and Lifelode, and two poetry collections. She reads a lot, and blogs about it here regularly. She comes from Wales but lives in Montreal where the food and books are more varied.

The NESFA Collected Zelazny is a stunning project.

Wow. Haven’t read this since I was 13 or so and all I really remember is the main character’s special way of avoiding graduation.

Re Zelazny short stories, I always loved A Rose for Ecclesiates – one of my top five sci-fi favorites of all time and a great way to see what the fuss is about with him. Re novels, my favorite was This Immortal but, of course, the first Amber series is near and dear. (Second one, while interesting, not so much.)

And, yes, everybody smokes in the Zelazy-verse. Akin to the pipesmokers in WoT.

Rob

I know this is minor Zelazny, but it’s nevertheless one of my favorites. I read it when I was at Carleton College (taking all sorts of courses, only some related to my major), because Carleton had a subscription to Analog, so I could check out (as in remove, not merely look at) the issues from the library, at least back to the 1960, possibly earlier.

Except that that Doorways in the Sand was published over three issues, and the third issue was missing. I wailed and gnashed my teeth, then asked the nice librarian for help. She pointed out that as a student at the college, I had access to a document request system. I duly filled out the forms, and a couple of weeks later, a smelly Xerox (the old type, before plain paper came in) arrived of the third installment. I don’t remember if I had any homework I should have done instead, but I’m quite sure that if I did, it didn’t get done until I finished reading.

I haven’t reread it in several years, but when I do, it always has the extra resonance of my own college time overlaid with the college of the actual novel.

This is my favorite Zelazny, but it’s been so long since I read it that I don’t remember why. I’ll have to re-read it soon, then!

I still remember when he died. I used to go to the book store and the first place I’d look in the Sci-Fi section was the Zs, hoping for a new Zelazny. I don’t do that anymore. So sad.

I remember this book distinctly. The whole Bide-A-Wee scandal thing still resonates in my brain and comes to the forefront whenever I read about someone freezing themselves in hopes of being revived in the future.

Going to school forever. Would be happy to do that, especially if I could switch schools every few years. An endless source of co-eds, too. Boy, I’d be a dirty old student.

“It’s a future without technology or social mores having changed much from the mid-seventies when this was written (published 1976) but apart from the way everyone (even the aliens) smokes cigarettes all the time, you almost don’t notice”.

I seriously noticed the plus-royaliste-que-le-Roi Australian, even then. The issue wasn’t his position on the monarchist-republican spectrum but his very un-British (and un-Australian) intensity about it.

I’m so happy NESFA is publising six volume collected Zelazny. I have the first four and am looking forward to the rest.

almuric@5 have you read the new Zelazny novel that came out January 27th this year, The Dead Man’s Brother? Not SF, but the narrator is a smart-ass, and I was pleased to read it.

P.M.Lawrence: I assumed that the Australian fanaticism about the Crown Jewels was something futuristic… and about on the same level of reality as an alien disguised as a wombat. Because, well, yes. I have been to see the Crown Jewels, in the Tower of London, they’re very nice, and in the circumstances in the book my only problem would be that I couldn’t give them to aliens fast enough.

What I meant by “don’t notice” was things like the lack of computers and cell phones and technological advances generally — sometimes futures written in the sixties and seventies look noticeably quaint because they don’t have them.

The last time I reread Doorways a few years ago, I was struck by the consistently light and cheerful tone. SF with no angst at all isn’t very common.

IRRC, The Shadow of the Torturer has the same “throw incoherent events at the reader, explain it in the next chapter” structure, and is more annoying with it because Wolfe’s style so challenging that I’m apt to wonder if I missed something rather than it not being included.

Nancy: You’re right, it isn’t. The bit I quote there about being tied up is a good example — normally, being tied up in the desert would warrant at least a little angst.

And you’re also right about the Wolfe, which is why despite recognising them as brilliant I cannot like them — I can’t get into a reading trance because they expect me to work too hard. I’ve only read it once. I’m not saying you always have to write a story the Red Queen’s way, but it does help comprehension, and if you’re doing something else you’d better be a genius like Wolfe and Zelazny.

I read this just before going to college, and I couldn’t wait to get there and climb all over the roofs at night. Which I did. I remember that and wombats.

Chiming in with another recommendation for the NESFA publishing the Collected Stories of Roger Zelazny having read the first two volumes. The volumes are beautifully put together and reading the Zelazny stories this way showcases the brilliance of his writing.

It took me a short while to really get used to the chapter structure in Doorways when I first read it, but not too long, really, given that the same in media res then flashback trick Zelazny used in each chapter of Doorways was used in large for Lord of Light, where the entire story is told in one large lump that way: Begin with Sam’s resurrection, then flash back to his life, then finally proceed forward to the end.

Ray: I found it less distracting in LoL because it was only done once. It was the repetition of starting each chapter with the middle that gave me reader’s whiplash.