I rode into Asheville, North Carolina, for all the wrong reasons, from the wrong direction, on a borrowed bike, with no weapons, ready to work for the vamps again.

Now that’s an opening sentence. Setting, tone, character, genre—it’s all here. Southern United States, character with big issues, signals of cool in bike and weapons, and aha! Must be urban fantasy. Whoever it is is working for the vamps, which as we all know, genre fans, means vampires.

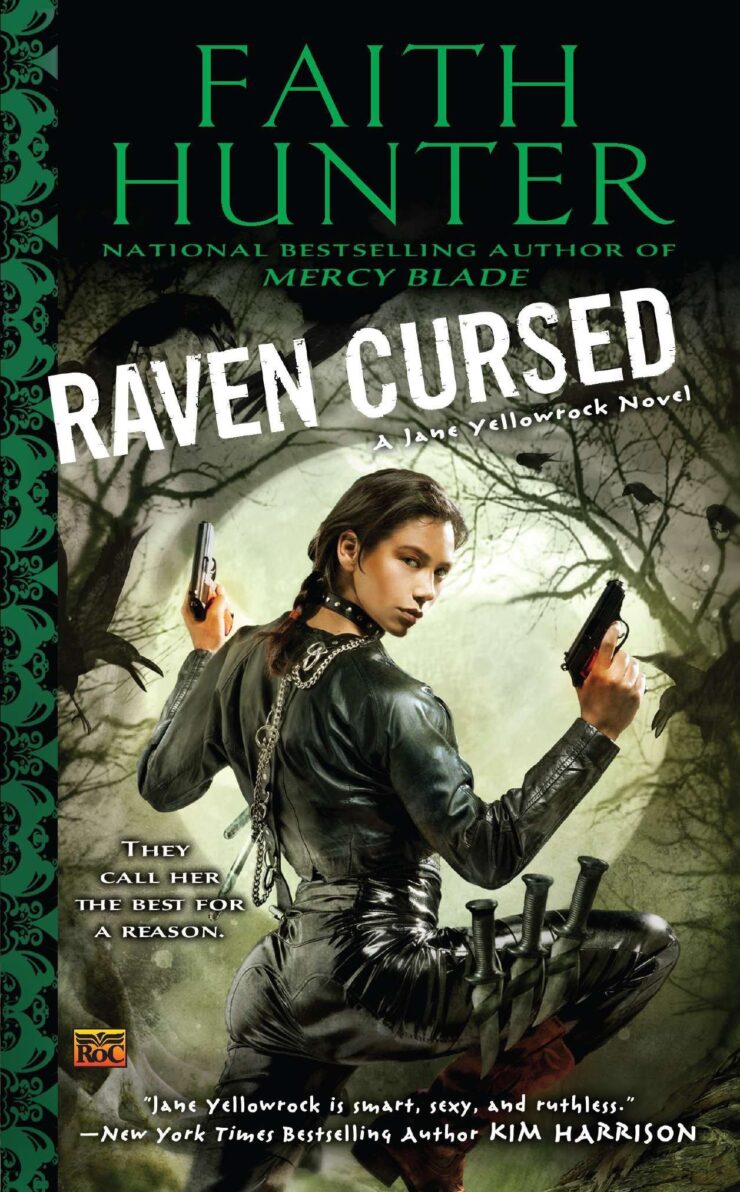

Faith Hunter knows how to pull a reader in. Her Jane Yellowrock series has been hugely popular for the past decade and more, and it’s earned its popularity. It hits the notes it needs to hit. Like all good genre fiction, it knows its tropes, it uses them well, and it puts its own spin on them.

Jane’s world is urban-fantasy classic. It does its vampires Anne Rice-style: They’ve always been with us, they’re drop-dead gorgeous, and Jane has a close personal relationship with a powerful vampire based in New Orleans. This world’s werewolves are dependent on the moon, they run in packs, and they’re vicious killers. There are other organized groups of shapeshifters, notably the black wereleopards of Africa. There are covens of witches everywhere; witches are, like vamps and weres, something other than human, though there can be human siblings in witch lineages.

And there’s Jane, who is a skinwalker. Jane is Cherokee, born before the Trail of Tears, with a story to explain how she’s still a young woman in the twenty-first century. Her brand of shifter needs genetic material from an animal in order to shift into that animal: skin, teeth, bone. DNA is the key here; according to the rules of Hunter’s world, shifters have always been aware of the snake inside the skin, the double helix.

In a further nod to contemporary science, a shifter has to make up mass if she shifts to a larger animal, and shed it if she shifts to a smaller one. It’s most efficient and least costly to the shifter if she defaults to animals that are roughly her own human size. Which for Jane means, for the most part, a mountain lion.

So far that’s fairly standard. But there’s a twist to Jane’s shifter identity. She shares body and mind with a second, independent consciousness, which she calls Beast. Beast was bound to her by black magic, and they’re bound for life. Jane still needs cougar DNA to shift into that form, but as long as she has even a tooth handy, she can shift at will.

There are rules and restrictions, and one great advantage. She shifts most easily around the full moon. Once she shifts, she’s confined to animal form until sunrise the next day. When Beast is dominant, she’s all cat, though Jane can influence her behavior. If Jane is wounded, she can use the shift to heal herself. She pays a price in pain, but it keeps her alive and functioning long after she might otherwise be dead.

It’s an intricate, complex world she lives in, and Hunter has expanded it, so far, to fifteen novels and numerous shorter pieces. I dipped into volume four, in which Jane contends with a crisis among the vampires, werewolves on a revenge-killing spree, and a witch gone seriously bad. Demon-compact-level bad.

What makes it stand out for me is its extensive network of female friendships. As a commenter noted on a previous post, adventure novels with Strong Female Characters—Mercy Thompson, for example—have a habit of defaulting to Smurfette Syndrome. There’s one Strong Female Character, and her friends and allies are male. Female characters are there to be rescued, or they’re villains or rivals, or they’re crowd extras. They aren’t part of the protagonist’s friend network.

Jane has female friends and chosen family, and they’re very dear to her. In Raven Cursed, she’s cut off from them by a combination of her own actions and the various crises that swirl around them, and it hurts her deeply. Her best friend is a witch; the witch’s family are Jane’s chosen family, and they have a freewheeling, sometimes contentious, loving and supportive relationship with one another. When one of them goes bad, it shakes the whole family to its heart.

They’re not Jane’s only friends, either. She’s actively sought out by a human member of the vampire clan, who honestly wants to be her friend. Jane is willing to entertain the notion, though she’s ambivalent. She started as a vampire hunter; she may be working for them now, but she’s not terribly fond of them. Still, female friendship is important to her, and she values it wherever she finds it.

That includes the female who lives inside her. Beast is all cat, but she’s comfortable with her human symbiote. She accepts their connection; she doesn’t challenge its existence, nor does Jane spend her life suppressing her animal instincts.

The one thing that may start to wear on the reader after a while is the way Jane avoids revealing what she is. A very few people know that she’s a skinwalker; quite a few more mutter portentously at intervals, “What are you, anyway?” It’s a big deal if someone figures out that the big kitty who saved them from the big bad is Jane. Since there’s never any question about who the vampires or the witches or the werewolves or the wereleopards are, I’m not sure why it’s so essential that nobody know about Jane.

But that’s a quibble. Jane and her Beast and her friends and allies, especially her female friends, are a grand cast of memorable characters. Their interpersonal dramas are as compelling as the magical and supernatural ones—sometimes more so. Jane, like a cat, is not exactly monogamous, and she moves among a delectable assortment of actual and potential mates and partners. It’s great fun.

Judith Tarr is a lifelong horse person. She supports her habit by writing works of fantasy and science fiction as well as historical novels, many of which have been published as ebooks. She’s written a primer for writers who want to write about horses: Writing Horses: The Fine Art of Getting It Right. She lives near Tucson, Arizona with a herd of Lipizzans, a clowder of cats, and a blue-eyed dog.