Tourists is a fantasy novel that perfectly captures the experience of being in a foreign country where you only sort-of speak the language and everything is strange. It made me think how astonishing it is that most people thrust into fantasy worlds cope so well and without any of this feeling of only half-getting what is going on and missing the significant subtext. Of course, in Tourists, some of what’s going on is magic, but only some of it. A lot of it has to do with Amaz’s history and current affairs. Also, Amaz is much more genuinely strange than most fantasylands.

Amaz is a fantasy country, but it’s somewhere you can fly to from the US. The American Parmenter family do that, crossing into a fantasy land by plane rather than through a magic door. They immediately recognise that it’s strange, but just how strange it is creeps up on all of them separately. The father, Mitchell, finds his colleague at the university is more interested in finding the magic sword described in his manuscript than in working on the manuscript. The mother, Claire, gets into taxis which magically take her where she wants to go, not where she asked to go. The younger daughter, Casey, goes to find her pen-pal and finds he is a guide to the magic. The older daughter, Angie, retreats into a fantasyworld of her own, one she is making up and writing about in notebooks, but which turns out to have a connection to the real Amaz. They’re an ordinary American dysfunctional family thrust into a situation they have no idea how to cope with.

If this was just a book about the Parmenters, it would be much more ordinary. It also contains the beautiful sections set in Twenty-Fifth November Street. These are like fairy-tales about a street of junk shops where strange and magical things happen. They are full of unexplained magical occurrences—a woman with tattooed palms leaves the tattoos on the back of her lover, a man with one ear who didn’t dream as a child and lost his ear to creatures in a nightmare—that the inhabitants take for granted. The stories are linked by the quest for the magic sword and by Rafiz, Casey’s penpal, who moves between the threads of the story. If it was just a book about Rafiz and Twenty-Fifth November street it would be magical realism (and deeply lacking in plot) as it is the two parts of the story dance together and make something new.

Amaz isn’t anywhere in particular—it isn’t even pinned down as to continent, and the customs and history of its people aren’t those of any real place or culture, or recognisably those of any specific place. It has telephones and taxis and planes and radio—it was published in 1994, so the absence of computers and internet isn’t surprising. I suppose as a fantastic country on Earth you could call it Ruritanian. What Goldstein really does well is making it work as a foreign culture tourists can’t quite get hold of from outside, where they don’t understand the issues, where they’re thrown because people will talk happily in English one day and ask why you haven’t learned their language the next. None of the tourists are really getting it but they keep trying to one up each other with how authentic they are. She makes Amaz work as authentically foreign, and she makes it work in its foreignness, she captures that experience so well, the culture itself is made up, the ways in which it is foreign are universal. I expect everyone has had the experience of being in a foreign country and finding the things that are the same as strange as the things that are utterly different, because of the different context, and of finding something that seems the same on the surface but which turns out not to be. Goldstein takes those universal moments and runs them through the novel.

For the people of Amaz, it’s business as usual. If your wife turns into a bird, that’s a pity; if you find a magic sword that’s nice. The very architecture and layout of the city are reflecting a struggle, and they take that for granted. One side uses jagged script and the other rounded script, and the struggle is reflected in the graffiti. Like a lot of things it’s clear to them even if it’s invisible to tourists. Goldstein invites the reader to consider both points of view, and the book is much richer for that.

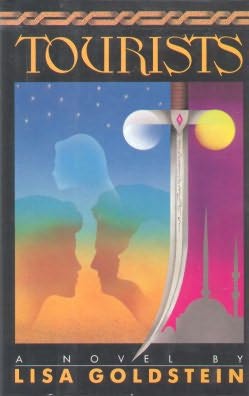

Finally, since I complain about awful covers, I’d like to say that as far as I’m concerned the Orb edition of Tourists has a perfect cover, and perfect use of fonts too.

By which I meant this cover which is unfortunately too small to use for the post.

I don’t often go on about books as physical objects, but Tourists is a book where I’m very glad I have the edition I do.

After I’d dropped out of college as a teen I read this book while staying in a hostel and had to copy out quotes from it into my journal because they were so perfect.

I found it a very reassuring book to read while feeling dislocated.

I love all of Lisa Goldstein’s work that I’ve read and had never heard of this novel. Thank you.

(Also the other Lisa, Lisa Tuttle.)

CliftonR: I also love Tuttle.

most people thrust into fantasy worlds cope so well and without any of this feeling of only half-getting what is going on and missing the significant subtext

Excellent point and one that totally makes me want to read this book (Goldstein’s various books have been on my vague “yeah, sometime” list for years), but it’s tricky, of course. Pamela Dean’s Secret Country trilogy, the first two? books are arguably very little *but* our POV characters missing the significant subtext, or at least not having any idea what’s going on, and if I hadn’t had all three (of your copies!) to hand and hadn’t cared about the characters, I might’ve stopped reading out of sheer bafflement.

You can also get a related effect, people thrust into fantasy who initially deny the validity of the experience–perfectly understandable and indeed likely realistic, but too much of that and we all know what we end up with . . .

Cool that you show the cover you do, even if it’s not to your liking. I did this for the original publication when I was fairly new to the business. It is very much of its time. Late 80’s.

I happen to find the original airbrush artwork in a drawer recently when I was cleaning out my studio.

If you are interested in some of my new work, you can visit:

lonkirschner.com

All the best,

Lon