Well, if you stop to think about it, yes. In the VanderMeers’ Steampunk anthology, Jess Nivins credits Poe as one of the mainstream writers who created “The American cult of the scientist and the lone inventor.” But Poe’s contribution to science fiction is vaster than a lone inventor character; he contributed authenticity and realism, and used his sci fi pieces as thought experiments. He is also among the first to focus upon the wonders of the great Steampunk icon: the balloon/zeppelin.

There is also the fact that Steampunk’s pater familias Jules Verne and H.G. Wells were heavily influenced by Poe. David Standish writes in his Hollow Earth: The Long and Curious History of Imagining Strange Lands, Fantastical Creatures, Advanced Civilizations, and Marvelous Machines Below the Earth’s Surface that “[Jules Verne] read Baudelaire’s translations of Poe in various journals and newspapers…and…Verne responded chiefly to the cleverness, ratiocination, and up-to-date scientific trappings Poe wrapped his strange stories in.”

At the core of many Verne works are Poe prototypes. “Five Weeks in a Balloon” was influenced by “The Balloon Hoax” and “The Unparalleled Adventures of Hans Pfaall”; “The Sphinx of the Snows” is like a sequel to The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket and is dedicated to Poe; Around the World in Eighty Days uses the main concept from “Three Sundays in a Week.”1

Verne’s most popular work, 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, may be the most subtly and heavily Poe-esque in its tone and character. Nemo’s silent suffering, his deprivation of human convenience paired with immaculate taste, and his blatant disdain for society all conjure Hans Pfaall, Roderick Usher, and Monsieur Dupin. Poe is so ubiquitous throughout 20,000 Leagues that at the journey’s end, the dazed Professor Aronnax describes his adventures as “being drawn into that strange region where the foundered imagination of Edgar Poe roamed at will. Like the fabulous Gordon Pym, at every moment I expected to see ‘that veiled human figure, of larger proportions than those of any inhabitant of the earth, thrown across the cataract which defends the approach to the pole.’”

H. G. Wells was heavily influenced by Poe’s mathematical descriptions of machines in such stories as “Maezel’s Chess-Player” and “The Pit and the Pendulum,”2 and acknowledged that “the fundamental principles of construction that underlie such stories as Poe’s ‘Murders in the Rue Morgue’ . . . are precisely those that should guide a scientific writer.”3

While I am by no means arguing that Poe’s Steampunk contribution is vast, his pioneering science fiction stories as well as his resonant influence in Verne and Wells warrants him a bit of steam-cred.

Poe’s Proto-Steampunk Stories

“The Unparalleled Adventure of One Hans Pfaall”

In “Hans Pfaall,” all of Rotterdam is in disorder when a balloon made of dirty newspapers descends to town square and throws a scroll to the mayor. The scroll is Hans Pfaall’s confession, a citizen who, with three companions, disappeared five years ago. While in Rotterdam, he escaped creditors and a nagging wife by reading scientific books, leading him to discover a lighter gas that would propel him to the moon. He murders his creditors and alights to space with three other ruffians, landing finally on the moon. Poe incorporates meticulous scientific detail, such as Pfaall’s expostulations on how to reduce hydrogen, calculations of the distance between earth and moon, and how gravity would affect the balloon’s levity.

In “Hans Pfaall,” all of Rotterdam is in disorder when a balloon made of dirty newspapers descends to town square and throws a scroll to the mayor. The scroll is Hans Pfaall’s confession, a citizen who, with three companions, disappeared five years ago. While in Rotterdam, he escaped creditors and a nagging wife by reading scientific books, leading him to discover a lighter gas that would propel him to the moon. He murders his creditors and alights to space with three other ruffians, landing finally on the moon. Poe incorporates meticulous scientific detail, such as Pfaall’s expostulations on how to reduce hydrogen, calculations of the distance between earth and moon, and how gravity would affect the balloon’s levity.

The moon’s actual distance from the earth was the first thing to be attended to. Now, the mean or average interval between the centres of the two planets is 59.9643 of the earth’s equatorial radii, or only about 237,000 miles. I say the mean or average interval;—but it must be borne in mind, that the form of the moon’s orbit being an ellipse of eccentricity amounting to no less than 0.05484 of the major semi-axis of the ellipse itself, and the earth’s centre being situated in its focus, if I could, in any manner, contrive to meet the moon in its perigee, the above-mentioned distance would be materially diminished. But to say nothing, at present, of this possibility, it was very certain that, at all events, from the 237,000 miles I would have to deduct the radius of the earth, say 4,000, and the radius of the moon, say 1,080, in all 5,080, leaving an actual interval to be traversed, under average circumstances, of 231,920 miles.

“The Balloon Hoax” chronicles a balloon voyage across the Atlantic, completed within 75 hours. Told through dispatches by Monck Mason, he describes atmospheric changes and geographical descriptions. Mason’s dispatches were factually saturated with speculations so accurate that “the first transatlantic balloon voyage, exactly a century later,” writes Poe scholar Harold Beaver in The Science Fiction of Edgar Allan Poe, “recorded almost the same number of hours and many of the incidents in Mr. Monck Mason’s log.”

Like Sir George Cayley’s balloon, his own was an ellipsoid. Its length was thirteen feet six inches—height, six feet eight

inches. It contained about three hundred and twenty cubic feet of gas, which, if pure hydrogen would support twenty-one pounds upon its first inflation, before the gas has time to deteriorate or escape. The weight of the whole machine and apparatus was seventeen pounds—leaving about four pounds to spare. Beneath the centre of the balloon, was a frame of light wood, about nine feet long, and rigged on to the balloon itself with a network in the customary manner. From this framework was suspended a wicker basket or car…. The rudder was a light frame of cane covered with silk, shaped somewhat like a battledoor, and was about three feet long, and at the widest, one foot. Its weight was about two ounces. It could be turned flat, and directed upwards or downwards, as well as to the right or left; and thus enabled the æronaut to transfer the resistance of the air which in an inclined position it must generate in its passage, to any side upon which he might desire to act; thus determining the balloon in the opposite direction.

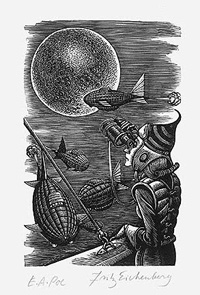

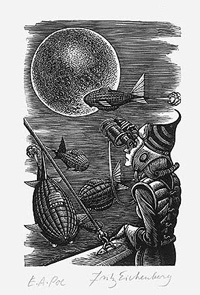

“Mellonta Tauta” may be the most Steampunk among these stories based upon its futuristic world and aesthetic (as the left Fritz Eichenberg’s 1943 illustration shows). It features a female character, Pundita, who writes to a friend about her ballooning cruise on April 1, 2848. Poe wrote this as a satire of not only American politics, but Western tradition, but also used it as a vehicle to espouse a water downed version of his scientific treatise Eureka. Pundita describes the sky as filled with balloon vessels not used for scientific exploration, but simply as a mode of pleasurable transportation.

“Mellonta Tauta” may be the most Steampunk among these stories based upon its futuristic world and aesthetic (as the left Fritz Eichenberg’s 1943 illustration shows). It features a female character, Pundita, who writes to a friend about her ballooning cruise on April 1, 2848. Poe wrote this as a satire of not only American politics, but Western tradition, but also used it as a vehicle to espouse a water downed version of his scientific treatise Eureka. Pundita describes the sky as filled with balloon vessels not used for scientific exploration, but simply as a mode of pleasurable transportation.

Do you remember our flight on the railroad across the Kanadaw continent?—fully three hundred miles the hour—that was travelling. Nothing to be seen, though—nothing to be done but flirt, feast and dance in the magnificent saloons. Do you remember what an odd sensation was experienced when, by chance, we caught a glimpse of external objects while the cars were in full flight? Everything seemed unique—in one mass. For my part, I cannot say but that I preferred the travelling by the slow train of a hundred miles the hour. Here we were permitted to have glass windows—even to have them open—and something like a distinct view of the country was attainable….

1Vines, Lois D. “Edgar Allan Poe: A Writer for the World.” A Companion to Poe Studies. Ed. Eric W. Carlson. Westport: Greenwood Press, 1996. p. 522.

2“‘The Pit and the Pendulum,’ with its diabolical machinery, is akin to the modern mechanistic story. Poe bridged the way for H. G. Wells’s use of mechanistic and scientific themes….” Hart, Richard H. The Supernatural in Edgar Allan Poe. Baltimore: The Edgar Allan Poe Society of Baltimore, 1936, 1999. http://www.eapoe.org/papers/PSBLCTRS/PL19361.HTM.

3 Vines, Lois D. “Edgar Allan Poe: A Writer for the World.” A Companion to Poe Studies. Ed. Eric W. Carlson. Westport: Greenwood Press, 1996. p. 521.

S.J. Chambers is an Independent Poe Scholar whose work has appeared inTor.com, Fantasy, Strange Horizons, The Baltimore Sun Read Street Blog, and Up Against the Wall. She has spent the last decade studying nineteenth century art and literature, and will be utilizing that knowledge as the Archivist for Jeff VanderMeer’s Steampunk Bible, forthcoming from Abrams.