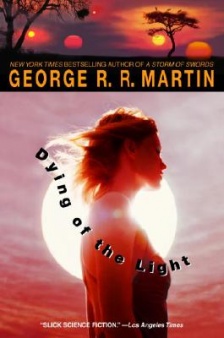

I don’t know when everybody else got into George R.R. Martin, but for me it was when Sandkings won the Hugo in 1980. I immediately bought two collections he had out, Sandkings and Songs of Stars and Shadows and (now subsumed into Dreamsongs) and his first novel Dying of the Light. I still own the scabby old Granada paperback I bought new for one pound twenty-five, with a typically stupid British cover for the period, featuring an irrelevant spaceship. (We didn’t expect much of our covers back then, and it’s just as well. In fact you could exchange this cover-picture with the cover of the same-era copy I own of Delany’s Triton and it wouldn’t make any difference.) I was fifteen when I bought those books, and ever since Martin has been one of my favourite authors. Dying of the Light is a book I have read too often, and yet I still love it, and can still read it. It was perfectly designed for me to adore it when I was fifteen, and I think it helped form my tastes in science fiction.

Dying of the Light is a poetic space opera set in the far future. It’s pretty much entirely set on the planet Worlorn, a wandering planet that has wandered briefly into the orbit of a sun. The nearby civilizations terraformed it and set it up for a ten year Festival as it passed through the light and warmth, and now as it is passing away from there the Festival is over and most of the people have left. The “dying of the light” is literal, and of course it’s metaphorical as well. The whole novel resonates to the Dylan Thomas line from which the title comes.

Dirk t’Larien comes to Worlorn because he’s been sent a message from an old lover, Gwen, who he knew years ago on Avalon. (“You can’t be any more sophisticated than Avalon. Unless you’re from Earth.”) Gwen is there to investigate the way the artificial imported ecology has adapted and merged. Since she left Dirk she has become caught up with the planet and culture of High Kavalaar—she’s in a relationship that’s much more complicated than a marriage. Dirk still might love her. High Kavalaar is very weird. As Worlorn goes into the dark the story plays out in deserted cities and strange wilderness among a handful of people far from their cultures but still entirely mired in them.

As well as this novel, Martin wrote a handful of short stories in this universe, and it feels like a real place, with real long term history and consequences of that history. He’s very good at tossing in tiny details and having them add up to a kaleidoscopic picture. He’s also very good at creating weird but plausible human cultures, and people who come from them and would like to be broadminded but find it a struggle. Worlorn has cities built by fourteen different civilizations—we only see five of the cities and three of the cultures. Yet the illusion of depth and real history is there—largely built by the names. Martin is astonishingly good at names—planet names, personal names, and the way that names define who you are.

Dirk (Didn’t you want to be called Dirk t’Larien? Not even when you were fifteen?) might love Gwen, but he definitely loves Jenny, which is his pet-name for her, or his version of her. Gwen’s highbond is Jaantony Riv Wolf High-Ironjade Vikary, and the parts of that name he chooses to use and not use reflect who he is and how he sees the world. He’s an interesting character, but the most interesting is his teyn, Garse Ironjade Janacek. Jaan is forward-looking and progressive, he’s been educated on Avalon, he’s loved Gwen, he sees beyond the cultural horizons of High Kavalaar. Garse doesn’t care about any of that. He grew up in the culture where men bond deeply to men and women are extra, where the bond between men is symbolised with an arm-ring on the right arm of iron and glowstone, and with women one on the left arm, made of jade and silver. He was quite content in this culture, and the very bonds that fix him to it bind him to Jaan and tear him.

This is a story of love and honour on the edges of the universe. It’s about choices and cultures. There’s duelling, there’s a mad flight through the wilderness, there are spaceships and anti-gravity scoots, there’s betrayal and excitement and lamenting cities singing sad songs as the world slips into endless night. It could easily be too much, but it isn’t—the writing is beautiful, and the characters are complex enough to save it. The book begins with a two page prologue about the planet. This is like beginning with the weather, it’s probably high on the list of things they tell beginning writers not to do. However, I adore it. It’s where we start getting names and history, all in the context of Worlorn, and the planet itself is certainly one of the protagonists. If you haven’t read it, I recommend reading this two page prologue to see if it hooks you.

I do learn things from infinite re-reads of books I know really well, and from writing about them. I just realised as I said that about wanting to be called Dirk t’Larien when I was fifteen that there’s only one woman in this book. Gwen is central, and who Gwen is and what she chooses is central, but nobody would want to be her or identify with her. She’s more than a McGuffin but not much more. Dirk (“You are weak, but nobody has ever called you strong”) has been drifting between worlds, he wants to believe in something, and the book ends with him making an altruistic choice. Any fifteen year old would want to be him, gender irrelevant. Gwen, though she has a job, is entirely defined by her relationships to men. It was a first novel—and how astonishingly good for a first novel—and Martin’s got a lot better at this since. Indeed, for 1977, Gwen was pretty good, and perhaps I shouldn’t complain.

Jo Walton is a science fiction and fantasy writer. She’s published eight novels, most recently Half a Crown and Lifelode, and two poetry collections. She reads a lot, and blogs about it here regularly. She comes from Wales but lives in Montreal where the food and books are more varied.