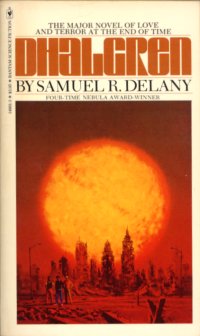

I went to New York this weekend, down on Friday, home on Sunday, to see the play Bellona, Destroyer of Cities, an adaptation of Samuel Delany’s Dhalgren (1975). I am planning to review the play, but first I want to talk about the book, which I re-read on the train on Friday.

Dhalgren is a really weird book. The weirdest thing is that it was a bestselling cult classic. Now I love Delany, but I find it the most impenetrable and the second least likeable of his books. I tried to read it several times as a teenager and couldn’t understand it. I finally made it all the way through, and I’m pretty sure I’ve read it all the way through twice before, very much on the principle of “maybe I’m old enough for it now.” Well, maybe I am old enough for it now, because I didn’t have any trouble reading it this time. I think Delany has written much better books, but even minor Delany is worth the time. But if one Delany book had to be a bestselling classic, why this one?

There’s an American city, called Bellona, in which an unspecified disaster has happened. The disaster, which has included riots and fire, lack of electricity and infrastructure, is still intermittently going on. The disaster may have caused something very weird to happen with time, because sometimes burned buildings are back the way they were and sometimes they aren’t, and the whole thing may be a loop. Time definitely isn’t working right in Bellona. The outside world is, we’re assured, getting on fine, but nobody knows what year it is and nobody is coming in to do anything about Bellona. Dhalgren isn’t a cosy catastrophe—or actually maybe it is, maybe it would be from the point of view of Roger Calkins, who we never see. Dhalgren, like Nova, uses myth to underline science fiction, and perhaps vice versa. The myths it’s using are some of them classical—Jason and Oedipus are both in there—and some of them modern, the kind of myth people may really believe, like “black men want to rape white women” and “women like being raped”. Dhalgren is about sex and violence, but it isn’t titillating about either of them, which makes one realise how much writing about both of those subjects is.

When talking about Dhalgren, it’s very tempting to talk about it as if it made sense. It deliberately doesn’t make sense—or rather it makes sense on a paragraph to paragraph level all the way through but not really on a wider scale. It’s a lot more like a poem than a novel, it’s allusive and hyper-specific. The beginning and the end are weird and experimental, the middle (probably 80% by volume) seems a lot more normal. The protagonist doesn’t remember his name, and even though he spends a lot of the book in a culture where people make up their own names (“Dragon Lady” “Nightmare” “Tarzan”) he never makes up a name for himself but takes one he is given—a name, and maybe an identity. The name is Kid, or the Kid, or Kidd, and everybody consistently sees him as younger than he is (he says he’s twenty-eight) and in the city a notebook comes to him and a pen with the notebook the gift of poetry. Is “kid poet” a role the city wants somebody to play? It’s certainly possible.

I remembered all the details about Kid’s poetry. I could have told you last week that the notebook has right-hand pages written on so he writes his poems on the left-hand ones, and they get published in a collection called Brass Orchids, and he’s accused of finding the poems too, and lacerated by a review. However, I had completely forgotten the whole thing with the Richards family, George, June, the elevator shaft—that was all like new to me. It’s all very vivid and very specific. So are the long rants about art from Newboy the poet and the balancing ones about the world and the moon from Kamp the astronaut. So is the stuff about his threesome, which I had remembered, and about the Scorpion nest which I mostly hadn’t.

The Scorpions are interesting. They’re like Hell’s Angels, or, as my friend Alter put it, like a Thieves’ Guild, only much more realistic than the kinds of Thieves Guilds you see in fantasy novels. In any other novel in 1973, the Scorpions would be the villains. They’re thugs, they’re into sex and violence, they beat people up, they loot and vandalize, they wear hologram projections of heraldic animals and underneath that black leather and chains. They also sort of protect people and sort of keep the peace, when they’re not the ones creating the mayhem. Delany doesn’t see them as villains, he makes you sees them as people, as different from each other, with different motivations. Being a Scorpion is a full time thing for some people, for others it’s something they do for a while. They’re destructive, not creative—but the people in the commune, the people with Projects they’re always trying to get somewhere with, don’t get anywhere either.

The thing is that in Bellona civilization has been taken away, and Delany’s looking at what that really means. Civilization isn’t electricity—it’s money, it’s having a job, it’s progress, and in Bellona those things are useless illusions. Anyone can have anything they want, and most people want very little. Calkins wants a big house and a houseparty and distinguished guests and celebrities and a newspaper and a monastery and a gay bar, and that’s why he’s the most powerful and enigmatic figure—we hear him but we don’t see him. Jack the deserter can’t believe he can have anything, and so he’s down and out, begging for a drink in a bar where the drinks are free. The commune—well, John and Milly anyway—want to organize projects but they went somebody else to carry them out, and that doesn’t work. The Richards family, and the people living in the store, are pretending that everything is normal white middle class America, they are living in denial. They are the people who would be ordinary people in the real world, and in most novels, and in Bellona they are the weirdest of all.

Which brings me to the interesting things Delany’s doing with race here. We’re told that the remaining people in Bellona are 60% black. There are a lot of black characters, and everyone, black or white, we get told what colour they are. There are only two Asians, one possibly “Eurasian”, which was a fine term in 1973. Kid’s mother is Native American, or Indian, as people said then. Most SF kind of ignores race as if it has gone away and skin color in the future is merely aesthetic, or else it focuses on it. What Delany does here is to have a group of people in a near future America where there is racism and there is tension and sometimes it matters and sometimes it doesn’t. Maybe this is one of the reasons I understood it better, because I understand US-style racism a lot better now. There are one and future race riots, there’s a black part of town where everything is worst, there’s the educated activist Fenster and the rapist George Harrison, after whom they name the second moon when it rises over Bellona who mirror each other. There’s a scene where a drunk gay white psychopomp claims he has a black soul and Fenster vividly denies him the right to it. Race, specifically the race relations between black and white in the US, is one of the iconic issues of the book, along with sex, violence, art, memory, civilization and love.

Most books written in 1973 have been overtaken by technology, but Dhalgren holds up really well on that. Clearly cell phones wouldn’t work in Bellona, and the internet wouldn’t any more than TV or radio. Computers aren’t mentioned because there isn’t any electricity. The near-future oooh tech of the chain of prism, mirror and lens, and the portable hologram projectors that work the Scorpion images and Lanya’s party dress, remain pleasantly near future oooh tech. If it wasn’t for Tak showing off his amazing futuristic machine that cooks with microwaves, it could almost have been written yesterday.

Dhalgren is a book long on images and short on explanations. One of the things about it that it isn’t possible to convey is how very specific it all is. Bellona’s light doesn’t vary except when the astonishingly large sun comes up, or the two moons, but the texture and weight of every moment, both physical and emotional, comes over with almost hypnotic clarity. You may not be able to say for sure what order events happened in, cause and effect may be hazy and time might loop, you certainly can’t say why a lot of things happened or what was going on in the larger scale, but it’s all incredibly vivid. We never get any answers about what’s really going on or why, and we never find out Kid’s real name. It’s very much a case of travelling hopefully—but it doesn’t feel unfinished or incomplete or unsatisfying.

For the review of the play, see next rock.

Jo Walton is a science fiction and fantasy writer. She’s published eight novels, most recently Half a Crown and Lifelode, and two poetry collections. She reads a lot, and blogs about it here regularly. She comes from Wales but lives in Montreal where the food and books are more varied.