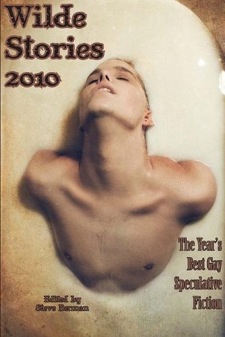

Third in a series of anthologies that have been building steam since their first release in 2008, Wilde Stories 2010 seeks to provide, as it says on the front, “the year’s best gay speculative fiction.” That first collection (2008) was nominated for the Lambda award for science fiction/fantasy/horror and all of the editions have provided hours of fascinating reading material. I enjoy these anthologies for the different perspective on speculative short fiction they provide by casting an eye solely on the best stuff with gay male characters from the previous year. While I’m usually a fan of “queer SFF” as a huge umbrella for any character of queer orientation, it’s also fun and revealing to look at texts limited to one slice of the pie, so to speak.

This year’s table of contents features award-winning authors like Elizabeth Hand, Richard Bowes and Tanith Lee (as Judas Garbah) and a variety of sorts of stories from horror to science fiction. The inclusion of female authors pleases me and is something that Berman himself comments on in his introduction—“Swordspoint happens to be my favorite (gay) novel… The author, Ellen Kushner, not only happens to be a woman, but when the book was released in 1987 she did not identify as queer… as far as I am concerned, the only reason you should look at the author’s names is to find more of their work. Let no prejudice stand in way of a good tale.” I could not agree more. (The gender-exclusion principle, that men cannot write lesbians and women cannot write gay men, is something I’d like to tackle in this space one day. It’s just so… fraught.)

By virtue of the fact that this is an anthology, I’ll review each story separately, quickly, and to the point.

“Strappado” by Laird Barron: Wilde Stories 2010 opens with this story, a horror piece about a man named Kenshi and a disastrous, nearly deadly encounter with a sort of “performance art.” It works on the principle of “I saw that coming” in the sense that you know exactly what’s going to happen within a page or two of the story starting and the discomfort it intends to produce in the reader works through that slow dread. While it is well written and definitely produces a sensation of discomfort and perhaps fear, I dislike that particular narrative trick, and so the story falls on the middle of my enjoyment meter. It is interesting and it does what it wants to do, but it didn’t blow me away.

“Tio Gilberto and the Twenty-Seven Ghosts” by Ben Francisco: This story, on the other hand, I did love. It is a bit of magical realism that tells a story of queer history, intergenerational understandings of what it means to be gay, and the sorrow and fear of the shadow of HIV/AIDS. It’s sad and sweet at the same time. The writer’s voice is also precise, engaging and lovely.

“Lots” by Marc Andreottola: This is one of those odd stream of consciousness stories. I was particularly entranced by the plant with the feathers. It’s a twisty and pleasantly confusing tale set in an alternate future in which something has Gone Very Wrong. It’s also frequently horrific, though I would hesitate to call it a horror story. It might be one; I’m not entirely sure. “Odd” really is the best word.

“I Needs Must Part, the Policeman Said” by Richard Bowes: This is another favorite of mine. It’s a story that plays with hallucination and apparitions, age and death—the way sickness can change a person, at the same time as how being exposed to something otherworldly can change a person. Bowes has a particularly strong voice that lends itself well to the visual experience of the narrative as he builds it in short, snapshot-esque scenes. The hospital and the dream/hallucination/otherworldly bits are equally crisp while the latter still maintain an air of strangeness and inaccessibility.

“Ne Que V’on Desir” by Tanith Lee writing as Judas Garbah: Lee/Garbah’s story invites a sort of flight of fancy, teasing you with wolf imagery and the wolves outside, then with the strange young man Judas has his tumble with. I enjoyed it thoroughly for the clarity of the narrator’s voice—you find yourself drawn into Judas’s speech patterns, which Lee does a marvelous job with. The language is particularly effective in a poetic, dreamy way.

“Barbaric Splendor” by Simon Sheppard: A story within the world of a different story, Sheppard tells of a group of Dutch sailors marooned in Xanadu and their captivity there—and as the endnote suggests, their eventual conversion to the ways of the Khan. It works as a bit of a horror story (the men who are held in the caverns below and the narrow escape from their teeth is particularly creepy), a bit of a fantastical tale. It’s engaging and the voice of the narrator feels fairly authentic.

“Like They Always Been Free” by Georgina Li: Interesting, short sci-fi piece that I had one quibble with—the apostrophes, lord, the apostrophes. The dialect would have felt smoother if it had just been dropped letters. The extra apostrophes everywhere draw attention to the stops in the sound of the speech instead of just letting the dropped sounds flow, which is how a slurred dialect of any kind sounds when it’s being spoken. When a story is depending on voice for its narrative, that voice has to sound just right and flow properly. There’s nothing wrong with the word choice, it’s great—I just want to cull the apostrophes so Kinger’s voice flows on without those odd marked stops.

Let that not convince you that I didn’t enjoy the story, because I still thought it was swift and good-strange.

“Some of Them Fell” by Joel Lane: Another story with an uncertain quality to it—we’re not entirely sure what was going on, but surely something a bit sinister. It’s also focused on a sort of coming of age narrative for the narrator, who moves from discovering desire as a boy and rediscovering the temporary relationship with Adrian again, all guided by the strange circumstances that had tied them together one summer. If I had to pick a tale from this volume that felt the most real, immediate and “true” it would likely be this one—it seems plausible, somehow. It’s also smoothly written and rather pretty.

“Where the Sun Doesn’t Shine” by Rhys Hughes: And of course, there’s always a humor story in your usual anthology—this is Wilde Stories’. A goofy and intentionally ridiculous short about vampires (who have switched over to drinking semen, not blood, and one character notes that the writer has given no reason for this) that is aware of itself on a meta-level and involved plenty of jokes about the writing.

“Death in Amsterdam” by Jameson Currier: A mystery-or-light-horror story with a rather open ending, Currier’s offering is perhaps the least speculative of all the tales—but it’s still engaging. It does feel more like a mystery story to me than anything, despite the end result of the narrator’s investigation being less than ideal. It’s well written and holds its tension throughout the run of the story.

“The Sphinx Next Door” by Tom Cardamone: I would call this urban fantasy—it has that certain feel, and is about a New York with certain other fae things inhabiting it. The narrator is not a particularly sympathetic man, and most of his problems seem to be of his own doing. The story has an odd trajectory that leaves me feeling as if I’ve missed something, or that there should have been a few more pages somewhere—the tension of the sphinx-next-door builds through the story to his eventual meeting with her and its outcome, but I was left wondering after more of a plot. The story didn’t quite satisfy me as a reader; your mileage may vary.

“The Far Shore” by Elizabeth Hand: This is by my reckoning the best story of the anthology—certainly the most dramatic and beautiful. The imagery of the birds and the boy-swan are perfect and so well-detailed that you can see it clearly in your mind’s eye. (I also have a deep personal weakness for birds, and so this story struck me in that way as well.) Hand weaves a tapestry of myth and reality through her so-very-believable narrator, who knows all the fairy tales from his time in ballet but doesn’t quite believe until he must, because he’s fallen into one of them. Fantastic, absolutely fantastic story.

As a whole, Wilde Stories 2010 is a thoroughly satisfying cross-section of genre stories from the past year that all feature gay protagonists—in some of the stories it’s tangential to the plot, and in some it informs the circumstances deeply (such as with “Tio Gilberto and the Twenty-Seven Ghosts”). Even those stories I had mild quibbles with were still enjoyable. It’s a quick read and the only thing I would ask for is a few more stories, because I didn’t quite want it to end.

Of course, there’s always next year.

Lee Mandelo is a multi-fandom geek with a special love for comics and queer literature. She can be found on Twitter and Livejournal.