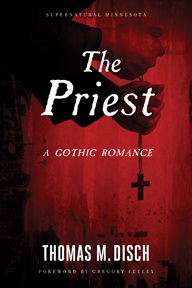

Thomas M. Disch was born in Iowa, but both sides of his family were originally from Minnesota, and he moved back there when he was an adolescent. Although he only lived in the Twin Cities area for a few years, the state left an impression on him, and between 1984 and 1999 he veered away from the science fiction for which he had become best known to write four dark fantasy novels which have become collectively known as the “Supernatural Minnesota” sequence. The University of Minnesota Press recently republished the entire quartet, and Beatrice.com’s Ron Hogan has set out to revisit each novel in turn, starting with The Businessman, The M.D., and continuing onwards.

The Priest: A Gothic Romance (1994) opens, like The Businessman, with a confused woman in a cemetery—quite possibly the exact same cemetery, since you’ll find the graves of the massacred Sheehy family here (although the date of their death has been erroneously pushed back to the late 1970s). Margaret Bryce isn’t a ghost, however. Her anxiety is entirely natural, brought on by a case of Alzheimer’s so severe that she fails to recognize her son, Father Pat Bryce, when he comes looking for her. She does remember one major detail, though, even if Father Pat doesn’t believe it: Her late husband was not his father.

That revelation does have a dramatic payoff much later, but it’s actually the least of Father Pat’s concerns, because his long history as a pedophile has finally caught up with him. He’s being blackmailed by somebody with evidence of his involvement with a fourteen-year-old boy who committed suicide after their liaison ended. “We don’t want your money,” though, his tormentor explains. “We want your soul.” Which is how Father Pat finds himself at a tattoo parlor on the northern outskirts of St. Paul, having the iconic Weekly World News photograph of Satan’s face in a oil well fire tattooed on his chest.

His blackmailer is a member of the Receptivists, whose beliefs are based on A Prolegomenon to Receptivist Science, an account by the science fiction writer A.D. Boscage of his abduction by aliens and his “transmentation” into the life of a medieval mason working on a Gothic cathedral in France. “Boscage had a fertile imagination as a SF writer,” the priest’s twin brother, Peter, explains, “and when he went around the bend, he continued to have a fertile imagination.” During their conversation, Peter also makes the explicit connection between Boscage’s story and Philip K. Dick, though he is willing to give Dick some credit for sincerely believing in the experiences described in Valis and subsequent novels (as well as the soon-to-be-published Exegesis). This roughly coincides with Disch’s own opinion; in The Dreams Are Stuff Is Made Of, he elaborates on how “Dick might have become the L. Ron Hubbard of the 1980s,” but had the “intellectual integrity” not to go down that path. (A brief description of Receptivist “debriefing” rituals reads like Scientology audits with a heavy overlay of Whitley Streiber’s UFO ideology.)

It isn’t too surprising, then, at least not to the reader, that Father Pat should himself be cast back through the centuries into the body of Silvanus de Roquefort, the bishop of Boscage’s cathedral—and, more chillingly, that Silvanus should awaken in a 20th century which he first believes to be hell, but later decides is “the realm of the anti-Christ,” where, as a sinner who has already been damned, he has very few restraints.

But we need to backtrack here: It turns out that one of Father Bryce’s other victims was Bing Anker, the one happy survivor of The Businessman, and he arrives at St. Bernadine’s to confront the priest, in the confessional, about the abuse. Disch also brings back Bing’s friend (and occasional lover), Father Mabbley, to serve as one of the few essentially decent priests in the bunch. At the time The Priest appeared, sexual abuse by priests was no longer a matter of whispered rumors; the Church was coming under heavy, open fire and Disch, who had been raised Catholic and had attempted to kill himself as a teenager in despondency over being gay, held nothing back. “You don’t think it’s an accident, do you, that every diocese in the country is having a scandal with pedophile priests?” Mabbley argues with a friend from seminarian days, who happens to be a high-ranking official in Father Bryce’s diocese. “We are the culture in which they breed, like excited bacteria.”

Disch carefully distinguishes between the gay priests (who, Mabbley estimates, number between 40-50% of the clergy) and the pedophiles—Father Pat keenly resents the disapproval of “lavender priests” who regard him “and those who shared his fleshly needs as diseased members fit only for amputation.” But it is the very hypocritical silence with which the Church camouflages its homosexual members that allowed the pedophiles to flourish unchecked. Yes, Father Pat had been caught once and sent to a clinic for rehabilitation—all that did, however, was make him more effective at not getting caught when he came back to Minnesota.

There is another monstrosity in this church, however, this one connected to the other great controversy of ’90s Catholicism: the increasingly heated debate over abortion. With the help of two overzealous parishioners, Father Cogling, St. Bernadine’s other priest, has used a remote, semi-abandoned shrine 200 miles north of the Twin Cities to house a “retreat” for pregnant teenage girls which is for all intents and purposes a prison where they can be held and prevented from having abortions. “The Shrine—with its enornmous ferrconcrete dome… and its immense subterranean comples of crypts, chapels, catacombs, and nuclear contingency command centers—was arguably the most imposing nonmilitary monument of the Cold War era,” Disch writes, after investing the site with a deliberate mish-mosh of fervently Catholic history. (There is a contemplative order called the Servants of the Blessed Sacrament, there was a historical figure named Konrad Martin, Bishop of Paderborn, and there was a massacre of the Jewish residents of Deggendorf in 1337 after rumors spread that a consecrated eucharist host had been stolen. None of these three things, in fact, has anything to do with the others.)

This is the place to which Father Cogling sends Father Pat to hide from the authorities after a particularly unsavory bit of business, unaware of course that his colleague’s body is currently occupied by an increasingly depraved Silvanus. As Gregory Feeley observes in his introduction to this new edition, it is the perfect setting for a Gothic melodrama, and the way in which all the novel’s plotlines converge here is a masterful bit of narrative design.

I want to discuss one more aspect of The Priest, but I should warn you: Doing so gives away the greatest of the novel’s secrets. While Father Pat languishes in medieval France, he encounters Boscage. (The clue that there’s another time-displaced person on the scene, the whistling of the opening three notes of “Yesterday,” can also be found in Tim Powers’s 1983 novel The Anubis Gates.) Eventually, another visitor from the future arrives, and he uses the opportunity provided by the Inquisition to torture Father Pat for his pedophile activities all over again. It seems like a lot of chips are falling into place…but Disch tears away all the supernatural elements in the final chapters. There was no time traveler, there is no tattoo, and there was never even a blackmailer: All Father Pat’s torments after learning about the suicide of one of his victims (and possibly some of the more lurid activities in which they engaged) are part of a paranoid fantasy stemming from frequent alcoholic blackouts. Father Pat believed he was Silvanus just like, as Mabbley explains in the penultimate chapter, Norman Bates thought he was his mother.

There is a consequence to this twist, though: It takes us out of the realm of the supernatural; with that in mind, it’s worth noting Bing shows no signs of the familiarity with ghosts he acquired in The Businessman. That bothered me at first; upon further reflection, I considered that The M.D. also had some casual overlap to the first “supernatural Minnesota” novel, but that there is no such overlap between The M.D. and The Priest. Nor could there be; Father Pat’s descent into madness takes place at a time when the dystopian future William Michaels was supposed to have set in motion would have been well on its way to fruition. Unlike Stephen King’s Castle Rock, where a chain of events is meticulously arranged over multiple stories to fit a consistent timeline, it seems Thomas Disch’s Minnesota, particularly the Twin Cities neighborhood of Willowville and the more remote Leech Lake, is more like Michael Moorcock’s Cornelius Quartet: a basic framework of people and places upon which the author can elaborate in any direction the story requires. Ironically, even after the supernatural aspects of the story have been stripped away, The Priest remains arguably the sharpest, and certainly the most suspenseful, iteration upon that template.

Ron Hogan is the founding curator of Beatrice.com, one of the earliest websites dedicated to discussing books and writers. He is the author of The Stewardess Is Flying the Plane! and Getting Right with Tao, a modern rendition of the Tao Te Ching. Lately, he’s been reviewing science fiction and fantasy for Shelf Awareness.