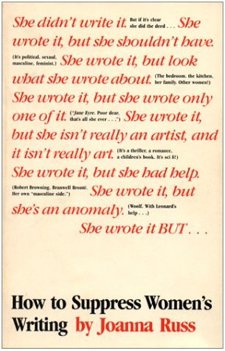

The cover of How to Suppress Women’s Writing by Joanna Russ is an eye-catcher. The lines of red text are a hard hook: “She didn’t write it. She wrote it but she shouldn’t have. She wrote it, but look what she wrote about. She wrote it, but she only wrote one of it. She wrote it, but she isn’t really an artist and it isn’t really art. She wrote it, but she had help. She wrote it, but she’s an anomaly. She wrote it BUT…”

The text that follows delineates the progression of marginalization and suppression as it works through each of these issues—as she says in the prologue, “What follows is not intended as a history. Rather it’s a sketch of an analytic tool: patterns in the suppression of women’s writing.”

Most readers are familiar with Joanna Russ’s famous work in science fiction, but she was also a critic and an academic. Of course, those things all go together, much like being a feminist and a speculative writer. This particular book opens with an SF prologue about the alien creatures know as Glotologs and their judgment of what makes art, who can make art, and how to cut out certain groups from the making of art. (They come up from time to time as a useful allegory in the rest of the book, too.)

The best part of this book is how concise and well-exampled each section of the argument is. Scholarly work has a tendency to be unnecessarily long and dense for no virtue other than a page count, but that’s no problem here. Russ cuts through the bullshit to use each word as effectively as it can be used and never lets herself stray from the outline of her analysis—in short, she brings the skills of a fiction writer to her academic work, and the result is an excellent text.

Its length and its readability make it possibly the most useful text on women and writing I’ve encountered in the past few years, because anyone can pick it up and engage with the content. There’s no threshold for the readership. She explains each of her examples so that even if a reader has no knowledge of the texts or writers being referenced, they will still understand the point. Plus, the examples are all hard-hitting and effective. Russ doesn’t pull her punches in her deconstruction of what has been done to the writing of women over the years—she wants it to be as clear as day that, even if it was done in ignorance or good intention, the disrespect and belittling of women’s art can’t be allowed to continue unremarked.

She also discusses briefly the way these same methods have been used on the writing/art of people of color, immigrants, the working class, et cetera. While her focus is on women, she recognizes that they are hardly the only group to be excluded and marginalized by the dominant power structure. In the afterword Russ admits her own unintentional bigotry regarding writers of color and her confrontation of it, a “sudden access of light, that soundless blow, which changes forever one’s map of the world.” The rest of the afterword is filled with quotes and writing by women of color. I find it heartening that Russ could openly admit that she was wrong and that she had behaved exactly as the people she was criticizing throughout her book, because everyone makes mistakes, and everyone can change. The acknowledgment of privilege is a necessary thing.

Which is why I think that How to Suppress Women’s Writing is a valuable text. If I were teaching a class on fiction of any stripe, I would use this book. For women who have spent their whole academic life reading anthologies where other female writers are included only as a pittance and with the “qualifications” Russ lays out (and that applies to the SFF world as heartily as it does every other genre). For men who, despite best intentions, might not have understood how pervasive and constant the suppression of a woman’s art can be.

It would be especially handy to give to a few people who insist that there’s no such thing as sexism in the writing world, genre or otherwise. It might make a nice point.

Russ never loses her cool or becomes accusatory in the text, though some of the examples might make the reader angry enough that they have to put the book down for a moment (me included). It’s engaging, witty and well-reasoned without ever plunging over the edge into “hopelessly academic.”

I recommend picking it up if you get the chance. It’s an older book, but the arguments in it are still valid today—though that isn’t actually a good thing. We have made so many steps forward, but we’re still not quite there, and reading books like this one can help.

Lee Mandelo is a multi-fandom geek with a special love for comics and queer literature. She can be found on Twitter and Livejournal.