Northanger Abbey is hilarious. It’s the story of a girl who wants to be the heroine of a Gothic novel, but who finds herself instead in a peaceful domestic novel. Throughout the book, the narrator addresses the reader directly in dry little asides. Catherine Morland is naive and foolish and very young, and while I can’t help laughing at her I also can’t help recognising my own young silly self in her—don’t we all secretly want to find ourselves in the books we’re reading? Or anyway, don’t we when we’re seventeen? Catherine is determind to think the best of everyone, unless they’re clearly a villain, capable of murdering their wife or shutting her up in an attic for years. She’s frequently mortified, but Austen deals gently with her, and she ends up in perfect felicity. This is not a book it’s possible to take entirely seriously, but it’s gentle and charming and exceedingly funny.

No one who had ever seen Catherine Morland in her infancy would have supposed her born to be an heroine. Her situation in life, the character of her father and mother, her own person and disposition, were all equally against her. Her father was a clergyman, without being neglected, or poor, and a very respectable man, though his name was Richard—and he had never been handsome. He had a considerable independence besides two good livings—and he was not in the least addicted to locking up his daughters. Her mother was a woman of useful plain sense, with a good temper, and, what is more remarkable, with a good constitution. She had three sons before Catherine was born; and instead of dying in bringing the latter into the world, as anybody might expect, she still lived on—lived to have six children more—to see them growing up around her, and to enjoy excellent health herself.

That’s the beginning, and if you like this, you will like the rest of it, because it’s all like that.

The world seems to be divided into people who love Austen and people who have been put off her by the classic label. I had to read Pride and Prejudice in school and it put me off her for decades. I came to Austen in my thirties, largely because of the Georgian Legacy Festivals we used to have in Lancaster. I started reading Austen as background for what was actually an awesome combination of theatre, microtheatre, and live roleplaying. (Gosh those were fun. I miss them.) I think this was a good way to come at them, as light reading and for their time, because there’s nothing more offputting that books being marked worthy. Austen’s a ton of fun.

It’s very easy for us reading Austen to read it as costume drama and forget that this was reality when she was writing. It’s particularly easy for us as science fiction readers, because we’re used to reading constructed worlds, and Austen can easily feel like a particularly well done fantasy world. There’s also this thing that she was so incredibly influential that we see her in the shadow of her imitators—her innovations, like her costumes, look cosy because we’re looking at them through the wrong end of a telescope.

There’s also the temptation to complain because she chose to write within a very narrow frame of class—neither the high aristocracy nor the ordinary working people attracted her attention. She was interested in writing about the class to which she herself belonged, though she went outside it occasionally—the scenes in Portsmouth in Mansfield Park for instance. The thing it’s easy to miss here, again because of the telescope and the shadow effect, is that very few people had written novels set in this class before this. More than that, very few people had written domestic novels, novels of women’s concerns. Before Austen, there weren’t many novels set largely indoors.

It’s also easy for us to read her books as romance novels, forgetting that Austen was pretty much inventing the genre of romance novels as she went along, and by Emma she had pretty much got tired of doing them. If she’d lived longer she’d probably have invented more genres. I was going to joke that she’d have got to SF before retirement age, but seriously genre as such wasn’t what she was interested in. She was interested in ways of telling stories, ways that hadn’t been tried before.

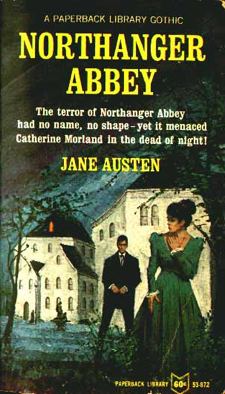

You can see this quite clearly in Northanger Abbey, which was the first book she wrote, although because of a typical irritating publisher delay it wasn’t published until later. She’d written a number of early brief attempts at stories, but the first book length thing she completed was this cool funny examination of how reading influences your life. Catherine reads Gothics, which were immensely popular, and she wants to be in one and she persistently imagines that she is. Her imagination shapes the world into one kind of story, and the world pushes back with a different kind of story. She is a heroine, as are we all, just not the kind of heroine she thinks she is. Catherine doesn’t get a gothic hero, she gets the kind and teasing Henry Tilney, she doesn’t get a mysterious document bur rather a laundry list. What her reading shapes isn’t the world but her own character.

And SPOILER when she does have the chance to be a Gothic heroine, when she is cast out penniless from the abbey, she copes with it in a practical and sensible manner and doesn’t even notice.

This isn’t my favourite Austen novel, that would be Persuasion where everyone is grown up. However, it’s a lovely book to re-read on a day when you have a cold and it’s snowing.

Jo Walton is a science fiction and fantasy writer. She’s published two poetry collections and eight novels, most recently Lifelode. She has a ninth novel coming out in January, Among Others, and if you liked this post you will like it. She reads a lot, and blogs about it here regularly. She comes from Wales but lives in Montreal where the food and books are more varied.

I started reading Austen by way of Jonathan Strange and Mister Norrell. That novel’s language was so wonderful I just had to have more, so I started reading Pride and Prejudice and ended up reading all of Austen’s novels.

That’s one good thing about pastiches or novels influenced by other authors – they sometimes make us read things we’d never had read otherwise. A series of novels about a detective in Tzarist Russia got me to read Crime and Punishment, and I actually enjoyed it!

my first exposure was when someone lent my wife a pride and prejudice dvd a couple of years ago … and now we’ve watched all the movies and read all the books and really enjoyed them. i was kind of hesitant at first – thinking they’d be mushy – but it wasn’t the case, and the characters are so well drawn … complex, interesting, and laugh out loud funny … there’s a lot of great insight into what makes them/us tick.

Jo – you are too funny. You keep hitting all my non-genre favorites (Austen and O’Brien in particular). Now you have me thinking about the common threads that tie them together.

But if you start blogging Carl Hiassen’s hilarious south Florida crime novels (my favorite is Skinny Dip – about a husband who tosses his wife overboard on a cruise, forgetting how strong a swimmer she was in college, and having her come back and start playing mind games with him) or Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes books, or David Sedaris nonfiction works, I’ll know you’ve somehow accessed my computer. Rob

This review is timely because I just finished reading Northhanger Abbey. This was the first time I ever read any Austen. Previoysly my only exposure to Austen was through the movies, otherwise I had succeded in avaoding them. My wife has read all of them and loved the movies and made me read this one. It was a rather good read.

Northhanger has always been one of my favorites, but most other Austen readers I know refer to it as her worst, and I’m never sure why. I think it requires a certain amount of knowledge about the gothic romances Catherine is always reading, or maybe it’s just that she is, as you say, very silly, as opposed to many of Austen’s other heroines, who are very clever. But with that in mind, I feel as though the narrator’s tone is such pure Austen, and it’s a book everyone should try out.

I read a fair amount of Austen in my teen years & then in college while studying English Lit, but I only read Northhanger a couple years ago. Knowing what she was spoofing made the experience hilarious. It’s not her most polished work, but it’s one of her most fun ones.

Thank you, Jo, for your continuing insights into my favorite authors, not only sf but recently including Patrick O’Brian and now Jane Austin. Austin has such a clear-eyed perception of people that she hardly seems dated, and like you I have also been puzzled that more people don’t see that she was inventing a whole new literature that only seems familiar or formulaic in hindsight.

The spoof of the gothic — one type of sf/fantasy — in Northanger Abbey makes it especially appropriate to consider here on Tor.com. But I am interested to hear that Persuasion is your favorite. Persuasion is almost my favorite, too, only very slightly behind Pride & Prejudice. I’ve written in the comments on the O”Brian posts that his books seems like books Austin could have written had she been able to go to sea with the Navy as most of her brothers did. After you finish the O’Brian books, would you consider giving us your take on the “naval officers ashore” in Persuasion?

How embarrassing. “Austen,” not “Austin,” of course.

I also came to Austen late because of being told in high school that Pride and Prejudice was very serious literature and I had to take it seriously and not laugh at all, and being bored out of my skull by it.

When I came back to it after watching a lot of Monty Python, I realized it’s supposed to be funny. The sense of humor comes from the same place. Why does no one tell students that Austen is funny?

Persuasion is also my favorite. I thought the recent spate of Austen + supernatural mashups would implode recursively if someone tried to do a supernatural version of Northanger Abbey…

I read Northanger Abbey a couple of years ago, after having read not only Pride and Prejudice and Emma (and there’s definitely something to be said for discovering Austen in one’s 30’s) but also The Castle of Otranto (the ur-Gothic novel), so I was kind of primed to get into this one. As funny as the genre-subversion was, for me the most striking scene was the one with the young man trying to impress Catherine by bragging about the speed of his carriage, and though Catherine suffers through it politely it’s clear she could not be less interested. It never occurred to me that such dialogues might have taken place before the invention of the internal combustion engine. Guess there’s nothing new under the sun, at least when it comes to human foibles.

Persuasion, eh? Thanks for the suggestion, and I’m moving it higher on my “must-read” list right away!