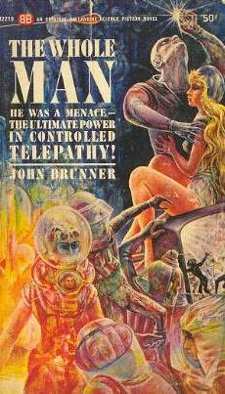

Telepathist (UK title) or The Whole Man (better US title) (1964) was one of the first science fiction books I read, one of the things that defined the edges of the genre for me early on. I’ve always liked it. It was also one of the first adult books I bought—I own the Fontana 1978 reprint (not pictured). Reading it now there are all those echoes of the times I read it before. It’s a strange book. It’s a fix-up, very episodic. All of the sections appeared in magazines before being put together as a book, and the seams show. It’s not as wonderful as I thought it was when I was thirteen, and it’s not as good as Brunner’s best work like Stand on Zanzibar. But it’s still an enjoyable read, and a thoughtful book about a crippled telepath in a near future. It has flashes of genuine brilliance, which were I think what always attracted me to it.

Gerry Howson is born in a time of troubles in a near future Britain to a selfish stupid mother and a dead terrorist father. The stigma of having unmarried parents has vanished so completely that I almost didn’t mention it, but it was real in 1964 and real to Gerry. But more than that, he’s born crippled, he lurches when he walks and never goes through puberty—we later learn that his telepathic organ is taking up room in his brain where people normally have their body image, so he can’t be helped. He is the most powerful telepath ever discovered. The book is his life story from birth to finding fulfillment.

Most science fiction novels are shaped as adventures. This is still the case, and it was even more the case in 1964. Brunner chose to shape this instead as a psychological story. Gerry Howson has an amazing talent that makes him special, but the price of that talent is not only physical discomfort but isolation from society. People recoil from him, he repels them. He’s better than normal, but he can’t ever be normal. Humanity needs him, but it finds him hard to love. The novel is his slow journey to finding a way to share his gifts and have friends.

Where it’s best is in the worldbuilding. This is a future world that didn’t happen, but it’s surprisingly close to the world that did—a world without a Cold War, with U.N. intervention in troubled countries, with economic depressions and terrorist insurgencies. It’s also an impressively international world—Gerry’s British, and white, but we have major characters who are Indian and Israeli, minor characters from other countries, and the telepathist’s centre is in Ulan Bator. This isn’t the generic future of 1964, and it feels grittily real. There isn’t much new technology, but Brunner has thought about what there is, and the uses of “computers” in graphics and for art before there were computers.

Telepathy is used by the peacekeepers, but what we see Gerry using it for is therapy—much like Zelazny’s Dream Master/“He Who Shapes.” (“City of the Tiger,” that section of the novel, appeared first in 1958, and “He Who Shapes” in 1965, so Zelazny may have been influenced by Brunner, or it may just have been a zeitgeist thing.) Gerry goes into the dreams of telepaths who have caught others up in their fantasies and frees them. This is done vividly and effectively, and the strongest images of the book come from these sections.

There’s also a wonderful passage where he befriends a deaf-and-dumb girl—in fact she rescues him—and is literally the first person who can truly communicate with her.

The last section is the weakest, with Gerry finding friends and acceptance among counter-culture students and discovering a way to use his talents to share his imagination as art. It’s emotionally thin and unsatisfying—and even when I was thirteen I wanted to like it more than I did like it. Gerry is more plausible miserable.

But this isn’t the story most people would write—yes, there’s the crippled boy who nobody loves who turns out to be the one with the amazing talent. It’s a good book because it goes on after that, it takes it further, what happens when you have the superhuman talent and you’re still unloveable and unloved and uncomfortable all the time? Where do you get your dreams from? I admire Brunner for trying this end even if he didn’t entirely make it work. You can see him stretching himself, getting less pulpy, becoming the mature writer he would be at the peak of his skills.

Jo Walton is a science fiction and fantasy writer. She’s published two poetry collections and nine novels, most recently Among Others, and if you liked this post you will like it. She reads a lot, and blogs about it here regularly. She comes from Wales but lives in Montreal where the food and books are more varied.