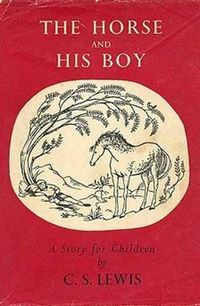

Alone among the Narnia books, The Horse and His Boy is not about children from our world who stumble into a magical land of adventure as its saviors, although some of those children make cameo appearances as adults. Rather, it is the tale of two children from that world seeking to escape the constraints of their societies and find freedom in the north.

And as you might be guessing, it is not without its problematic elements.

The book begins when Shasta, a young boy living far south of Narnia, makes two important discoveries: one, his father is not really his father, and two, Bree, the horse currently overnighting in the stables can talk. Putting these two facts together, the horse and his boy decide to flee to Narnia and the north. Along the way, they meet a young girl, Aravis, who just happens to be riding another talking horse, Hwin, because lions just happen to be chasing all of them. Things do just happen in tales of this sort. The four all agree to travel together to the north for safety, but some bad luck—or great fortune—along the way just happens to let them find about some treachery towards Narnia and its neighbor, Archenland, that they might, might, be able to stop in time, if they can force themselves to travel quickly enough and stop thinking about water all the time. Three earlier characters—Susan, Lucy and Edmund—make cameo appearances as grown-ups.

As you might be gathering, The Horse and His Boy relies just a little too much on coincidence. (Which Lewis somewhat airily explains away by saying that Aslan is behind most of this. Of course.) But for all that, this is one of the more neatly plotted of the Narnia books, with a tightly wrapped up conclusion and a prophecy that actually makes sense, marked by a few distinct elements.

The first is the setting, which, for the most part, is not in Narnia, but in Calormen, a vaguely Islamic-style empire, loosely (very loosely) based on the Ottoman and Persian Empires. (I said, loosely.) For a series of books emphasizing Christian theology and symbolism, this sudden choice of background feels a bit, well, odd.

Most of this discussion belongs more properly to The Last Battle, where the Calormenes take on a considerably more sinister, problematic and, I fear, religious role. Here, aside from the occasional plot to murder their sons, a penchant for underage wives, and an embrace of slavery, the Calormenes are not described as inherently evil. Indeed, a few seem like very decent people, and one, of course, is the heroine of the book. This is actually a refreshing change; in other Narnia books, those who denied or simply didn’t like Aslan were instantly marked as evil.

At the same time, I find it somewhat distasteful that the young, dark skinned Muslim girl had to flee to the kindly, courtly lands of the white people in order to find freedom, because only her Calormene family and friend would urge her to enter a horrific marriage with a man many times her senior, just because he was rich. These sorts of marriages of young women to wealthy older men happened in white, Christian cultures as well, and the scholarly Lewis knew this quite well. And it is also somewhat odd to hear the constant cries of Freedom! Freedom! Narnia and the north! given that both Narnia and Archenland are monarchies believing in the divine right of kings. (Not to mention all of those giants, mentioned in a sidenote here, who are, we are to understand, not exactly engaging in democratic practices.) Yes, this is a work of its age, and the very welcome that Aravis receives in the north, despite her background, speaks well for Lewis’s comparative tolerance. But this element is still there, and will be revisited later.

The second element is Aravis, the next in the series of really cool girls. Aravis is a trained storyteller, a tomboy, and quite capable of doing whatever she needs to do to get what she wants. She is, hands down, the most ruthless protagonist the series has seen so far, and she is the first to receive a direct, physical punishment from Aslan in return. And yet, she is sympathetic: the marriage she wants to escape is truly hideous (the glimpse we get of her prospective bridegroom actually makes it seem worse); bad enough for her to consider suicide. (If this seems extreme, she is probably about twelve, if that, and her prospective bridegroom is at least 60, if not older.)

She is cool in other ways as well: she knows how to use weapons and armor, and finds parties and gossip and the like all too boring. She has her distinct faults: that ruthlessness, and her pride (which Shasta finds very silly). But, as Lewis says, she is as true as steel.

And, despite her outright rejection of her society’s gender roles (they aren’t excited about her learning weaponry, either) she is the only one of the five girl protagonists in the entire series to get married. (Caspian does get married, off screen and between books, to a girl who has only a few lines of expository dialogue.) To be fair, if we are to believe Lewis’s timeline, at least two of these other girls never really had a chance, and we cannot be sure if a third married or not. But since Lewis elsewhere embraced very traditional gender roles in the books, making a point of the differences between girls and boys, having only the tomboy marry, whether an accidental or purposeful artistic choice, seems… odd. On the other hand, it shows that Lewis, who was, after all, to marry a career-minded woman (this book is dedicated to her two sons) did not believe that marriage was a woman’s only destiny.

Sidenote: The alienation of Susan that I’ve mentioned before makes a reappearance here. Colin calls her a more “ordinary grown-up lady,” comparing her to the sympathetic Lucy, “who’s as good as a man, or at any rate as good as a boy.” Susan’s inability to see beyond appearances nearly dooms Narnia and Archenland to conquest and slavery. And, she is unable to save herself from an unwanted marriage, instead needing to rely on her courtiers, brother, sister and pretty much the entire country of Archenland for help. This would be less bad if it did not occur in the same book where the comparatively powerless Aravis coolly saves herself from an equally unwanted marriage.

If you’re reading along for the first time, get worried for Susan. Very worried.

This is also the book where Lewis tackles the issue of fairness head on, when when Shasta, after what most dispassionate observers would consider a rather unfair series of events (a childhood spent in slavery, a horrific trek across a desert to save a country he knows nothing about, getting chased by lions, and getting lost in foggy mountains) spends some time complaining to a Voice. The Voice, which turns out, of course, to be Aslan, explains calmly enough that all of this bad luck is no such thing, but, instead, has been part of a nice divine plan. Well. It comforts Shasta, at least.

I’d be remiss if I left this book without mentioning the most delightful part: the two Talking Horses, pompous Bree and quiet Hwin. Bree provides the book’s humor; Hwin provides the soul, and much of the practical planning, in another quiet instance of this book’s girl power. If you like horses, talking or not, you will probably like this book.

Mari Ness spent some time looking hopefully at horses after reading this book, but never found any who would talk to her. She lives in central Florida.

Freedom in most societies means that the people in charge step on your neck lightly most of the time.

And no, i’m not just talking about dictatorships.

Thank you for the write up. It is a marvelous coincidence that I am currently making my way through Narnia – for the first time since I was young – and I was just about to start this book (I’ve chosen to read them in Narnia chronological order rather than publishing order).

I find your comment about monarchies to be odd. It’s perfectly possible for the King to be just and fair and to let his people see to their own affairs for the most part—in other words, there’s no inherent contradiction between monarchy and liberty. (Nor is there any guarantee that democracy equals liberty, but since there are no democracies in Narnia that doesn’t have much relevance to the story.) The Narnia we see is one in which the kings and queens don’t seem to do much other than ride horses and wear pretty clothes, and the humans and animals of Narnia seem to be happy and free in every important sense.

As for Susan, I’ve always been a little mind-boggled that Susan not only grew up but married in Narnia, and then somehow went back to being a young, single, and presumably virginal adolescent when the Pevensies returned through the wardrobe.

the Calormenes are not described as inherently evil

I always liked that about this book, and always felt kind of betrayed in The Last Battle when they turn out to be evil after all. (Among other betrayals in TLB, that is.) The scenes in the city of Calormene felt far more fantastical than anything else in the books, except for some of the later bits of Dawn Treader.

Unrelatedly, “Does it ever get caught on a hook halfway?” may be the most delightfully impertinent line in all of children’s literature.

The trope of the beautiful, brave, intelligent Muslim woman who chooses Christianity and marriage to the hero is a constant in medieval French literature, which is what Lewis’ dayjob was. They usually appear in epics, and Charlemagne is their godfather more often than not. Epic Christian women were rather wet in comparison.

I remember the Calormene scenes differently, bearing in mind that I haven’t read them in probably a decade. Wasn’t there a scene in a souk where Shasta saw the Northerners for the first time, and was struck by their free, proud demeanor–which, he thinks, isn’t at all like the sniveling Calormenes he’s used to. I hope I’m wrong, but ISTM that similar remarks happen throughout the books.

This is actually my favorite book from the whole Narnia series. It’s much more interesting than the other books and has almost no Christian metaphors, except at the very end when the action moves to Narnia. If it weren’t for that bit, the book could completely be a stand-alone novel, it’s so different from the rest of the series.

I don’t think the Calormenes are shown as inherently evil even in TLB. One of the invading army is shown as noble and loves Aslan as soon as he knows him.

I always found Lewis’s portrait of the (idealized) Narnian/Archenland model for monarchy memorable. They may be kings by divine right, but they aren’t absolute monarchs. “The King’s under the law, for it’s the law that makes him a king. … For this is what it means to be a King: to be first in every desperate attack and last in every desperate retreat, and when there’s hunger in the land (as must be now and then in bad years) to wear finer clothes and laugh louder over a scantier meal than any man in your land.”

My confidence in the ability of hereditary monarchy to actually produce such paragons reliably is nonexistent. But it’s an enviable model for rulership if you can get it, and it’s a striking contrast to the power fantasy most kids (most people) bring to the idea of being a king (or, these days, a princess).

I like this book very much for many of the reasons that the post describes. All four main characters — the two children and the two horses — are terrific, the story is exciting, and the worldbuilding is interesting. But I think we must acknowledge frankly the problematic and all-but-racist treatment of the Calormenes. The book’s point of view is quite clear: Dark-skinned Southern (Islamic) people are at least sneaky, insincere and cruel, if not always evil; light-skinned Northern people are honest, forthright, handsome, and fair.

I also do not see how The Last Battle is worse on this score: Lewis goes out of his way in that book to show an honest, forthright, handsome and fair Calormene soldier. The other Calormenes adhere to stereotype, but its only by reading A Horse and His Boy that we know what the stereotype is.

Man, do all my favorite childhood books have racist elements?

This was always my favorite of the books. Because Shasta was fun and interesting, yes, but mainly because Aravis was awesome and clever. I was always jealous of Shasta getting to marry her in the end. ;)

Susan definitely seemed a wet noodle in comparison.

The horses are my favourite: Hwin’s puncturing of Bree’s false pride is lovely.

This was always my favourite of the series, mostly because of the two main female characters: Aravis was so competent and Hwin so sensible that they outshone Shasta and Bree.

Since I found The Last Battle a dreadful let-down, and never wanted to re-read it, my view of the Calormenes depends very much on this book. I think that, as a people who don’t follow Aslan, it’s fairer to compare their treatment to that of the Telmarines in the previous books, rather than to that of the Old Narnians and Archenlanders. I don’t think the Tisroc and Rabadash come out any worse than Miraz and his henchmen.

Two things that really struck me when I was a child were the way that Lewis praises the Calormene storytelling tradition, and the wonderful food. Maybe his asides about how no one actually wants to read school essays, while everyone wanted to hear a good storyteller, were from bitter expereince as a college tutor. Certainly, the exotic food would have particular resonance in 1950s Britain, coming after a decade of food rationing.

The other thing that struck me , even then, was the level of inconsistency: where Mr. Tumnus in The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe has books with titles like Is Man A Myth?, it turns out here that there is a country with a human population within a few hours’ travel. The whole big deal about the Sons of Adam and Daughters of Eve is rather undermined.

jaspax@3: As for Susan, I’ve always been a little mind-boggled that Susan not only grew up but married in Narnia

But she didn’t marry anyone.

Azara@12 While of course the real answer is that Lewis hadn’t thought of Archenland when he wrote LWW, there’s at least a possible handwave: According to The Magician’s Nephew, Frank and Helen’s sons married nymphs, and their daughters wood-gods and river-gods. If that’s the founding population of Archenland, maybe they don’t qualify as Sons of Adam and Daughters of Eve anymore for the purposes of the prophecy.

Of course that still leaves the question of where the Calormenes came from, and why none of them could do it. (As of Prince Caspian, we might have thought that they hadn’t yet shown up during the Pevensie reign, but of course this book establishes that they were there.)

@HelenS, but I thought she did? Shows how well I remember, I guess.

I too wondered why a being as powerful as Aslan could not have found a less abusive foster parent for a baby to fall into the hands of.

Also why a name could not have been found that wasn’t obviously stolen from American geography (a friend of mine thought Shasta was named after a soft-drink brand.)

His not being enthusiastic about kingship was an interesting revelation for a then-not-questioning-enough reader. But I repeat that just as in “Dawn Treader” I distrust this whole destiny/divine right thing if it screws up a person’s life.

Was rather squicked at the detail of Aslan ripping up Aravis’ back, even given the reason for doing so. Still don’t know how I feel about that one. There might have been a more constructive way to make it up to the whipped maid.

I’d say that this was my least favorite of the series, perhaps just from the setting [not a desert person.] But I did appreciate Aravis, and felt that her marrying the boy when grown was somehow a copout [but I’m not a marrying person either.] Seems to me that they should learn how to not be fighting all the time in the first place. A Hwin/Bree match would have seemed more suitable.

I have to agree with Farah Mendlesohn @11 – the two horses are what really made the story.

I never had any problem with the idea that Aslan was the one chasing both Hwin and Bree so that they might have a chance together at reaching their freedom. Of course, it did help at the time that I bought into the mythology.

CS Lewis was of course writing from a long tradition of presenting Islam and Muslims as pagans of the worst sort – in one of his religious books he speaks approvingly of the Crusades. Anyone who knows what the Crusaders actually did, doesn’t do that.

And like I say, it’s one of my three favourites Narnia books because it’s got nearly all of the elements of a good story, and it does them well.

@mrburack – Point taken.

@jdubb – You’re welcome!

@jaspax – Lewis had also extensively studied medieval chronicles and literature, as well as its surrounding history (it helps to know about the Peasants Revolt of 1381 before tackling Piers Plowman, for instance) and was well aware that peasants and nobles frequently rebelled against kings claiming to rule by divine right. In some (not all) of these rebellions, the rebels argued that the king was also restricting various individual freedoms (often religious), or that particular king had no political authority over that part of land and no authority to restrict certain freedoms (also, often religious). I need to add that applying contemporary terms to medieval rebellions is…problematic, since medieval rebellions were generally speaking about different things than, say, the recent Cairo protestors. Nonetheless, Lewis knew enough about resentment of kings — and even featured a bad king and a rebellion – to know that saying “freedom” in the context of a divine monarchy can be just as problematic.

Mind you, @Mrburack’s point is well taken, and certainly individual freedoms can exist in a monarchy, and democracy does not guarantee individual freedoms, particularly for members of marginal groups – and Lewis is absolutely talking about two members of marginal groups here, Shasta, who starts as a slave, and Aravis, facing a child marriage. But I still find, especially in a quasi-medieval context, the statement odd.

@jazzfish – Oh, we’ll be talking about that when we reach The Last Battle. A lot.

@TexAnne – No, you’re right – that does appear in this book, but, and it’s a debatable but, in my opinion Lewis also shows that not all Calormenes are like that – the various Calormene warriors and nobility, for instance, seem to be pretty proud folks. Shasta mostly seems to be comparing the servants – the Calormene servants are slaves, who can be beaten for very little reason at all (like Aravis’ slave, who does nothing wrong and gets lashed for it); the Narnian servants aren’t slaves and aren’t getting whipped.

@dova113 It’s always been one of my favorites, too.

@MadLogician – Well, I’ll be discussing that more in The Last Battle, but I do think they are portrayed far more negatively – with the one exception – in that book.

@Michael S Shifer – To be fair, I expect that some of that came from the British Royal Family; the Duke of Gloucester served in the Army and was slightly wounded by a bomb; the Duke of Kent was killed while on a mission that Wikipedia has some excited speculation about (don’t ask me). And of course George VI and his wife famously stayed in London even as the city was getting bombed. So Lewis definitely had real life examples of royals entering battle before him.

In general I completely agree with your comments about hereditary monarchy :)

@wsean – Not all of the Oz books had racist elements! Just, um, some of them! We’ll just see what happens when I start tackling the next set of books…

@farah Mendlesohn – I love Hwin’s, “Well, the important thing is to get there, right?”

@Azara – I found that myth punctured right in Wardrobe when all of those kings and princes started showing up to woo Susan – I mean, yes, I appreciate the fanwanking that maybe they weren’t actual Sons/Daughters of Adam/Eve since they’d all married river gods and so on, but, um, still. Here….yeah. I see no reason for Narnia to be so freaked out by humans when there’s a huge city that takes a full day to walk through filled with humans just a couple days away. One good reason not to read the books in publication order.

@HelenS and @jaspax – Susan is courted by a lot of men, but for whatever reason – never stated in the text – she never marries. When I was a kid I thought this was because she always knew at some level that she’d have to go back to England, and her spouse wouldn’t be able to follow here. I wonder now if part of her reluctance to leave Narnia on that first trip is because she did meet someone – and if part of her attitude on her second trip comes from those memories. But that’s fanwanking and not in the text.

@Angiportus – I think I’m ok with Shasta and Aravis marrying in part because she’s so cool, and in part because it’s only the second time any protagonist marries in the series – and the first time happens offscreen. I think I might have a problem if Lewis was pairing off more people, but, Shasta and Aravis took a long trip together, understand each other (even if she is from a considerably wealthier background) and have much of the same beliefs in honor and so on. So it works for me.

And, well, although Bree and Hwin took that same trip, Bree, even after his humiliation, still seemed too fundamentally proud for Hwin – plus, I can’t see him agreeing to marry anyone who saw him at his worst. So I’m ok with the two of them deciding to marry other horses.

I didn’t think Aslan was trying to make things up to the maid – I don’t know that anyone did try to make things up to the maid. I think he was trying to show Aravis that, hey, a whipping is not a casual thing, it HURTS, so think a little before you create a situation where a slave might get whipped. It was a nice sign that someone was thinking about the slaves.

@gorbag – I’ll have a lot more to say about Lewis’ attitudes towards Muslims later.

Thank you so much for doing this series; it’s been really interesting so far. I’d never noticed that Lewis didn’t really write fleshed-out and interesting girl characters until after he met his wife. I don’t know that I knew the publishing order of the books, though–I have a numbered set starting with The Magician’s Nephew and ending with The Last Battle. I can’t remember what order I first read them in anymore, however.

The Horse and His Boy is one of my favorites of the series, and has been for a long time. I, too, like the pragmatic Hwin and the skilled Aravis, and I think it’s fun to see Susan, Edmund, and Lucy as adults. Although they use “thee” and “thou,” don’t they? I’ve always thought it a bit odd that the Pevensies start using the informal 2nd person when they wouldn’t have been raised using it. I guess they picked it up from their courtiers?

Re: the sudden appearance of an empire full of humans when there weren’t any in The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe, I’ve always just assumed that the White Witch somehow prevented anyone from entering or leaving Narnia. So there was no way for the animals et al to escape from the White Witch and no way for the humans in Archenland, Calormene, etc., to enter Narnia. I could be completely wrong, though.

This is one of my favourites, aside from the Magician’s Nephew. I’m sure that I didn’t really think about all the issues when I read it for the first time re Calormen although I did think it odd that they are so close to Narnia, and also that it was a bit odd Susan thinking about marriage given that she does go back as a child. I wonder what would have happened if she had married? Why didn’t Peter think about marrying being the High King and all? Unfortunately the series doesn’t really hold up to any scrutiny re chronology / geography / consistency which is a great shame – needs a bit of ret conning I think.

There is a history of slave traders taking people from the West Country and Ireland even in the 1600s for sale in the Ottoman Empire so Shasta (why would he be named after an American place? Where is that?) fits in with that. I don’t see the whole thing being arranged by Aslan, just that he gives Shasta that little bit of aid throughout – the knight getting to the shore, helping Shasta and Bree escape – but Shasta has to move the whole plot; it isn’t pre-determined. Aravis was one of my favourites – I didn’t really notice consciously the lack of strong girl roles but it was certainly great to encounter one who was a bit more kick arse.

Lots of fantasy authors mine the atlas for interesting names. Caspian and Shasta are both geographic features (I still remember my great shock of wonder at discovering that there was a real Caspian Sea on the globe) and there is a Mount Shasta in California (after which a brand of soda is, or was, named).

The hundred years’ winter would have cut them off from Calormen and even Archenland, I thought.

These sorts of marriages of young women to wealthy older men happened in white, Christian cultures as well, and the scholarly Lewis knew this quite well.[/i]

But sometimes, a story is just a story. Narnia is not[/i] Western Christian Europe, even though it may be modelled on it. So in Narnia, children aren’t married off to older wealthy men. It’s fine to analyse the meaning behind stories, and it’s interesting (I like it), but sometimes you just have to suspend disbelief and realise that while there may be similarities, there are differences too, and Aravis running away to Narnia to avoid her marriage because such things don’t happen there is consistant with how Narnia is.

I didn’t say Aslan was trying to compensate the maid–I was saying he bloody well ought to have done so. She doesn’t even get to see what Aravis went thru.

@21. ClairedeT – yes, after I’d had a few more years of reading other authors of widely differing skills and had gained some distance from CS Lewis, I began to see that he had left far too many gaps and holes in his world/s and had endeavoured to fill them with various adhockery itsabitsas. It made re-reading him too difficult for a long while, and now I don’t even have a complete set.

Disappointing.

Ahh this book. It’s definitely my least-read of the Narnia series(not like I’ve read the others a ton..I’ve probably read most of the Narnia books 3-4 times. Pretty sure I’ve only read this one twice!) For some reason, it just doesn’t have the feel of a Narnia book to me…I think I was disappointed the first time I read it, just because Eustace and Jill are pretty much my favorite characters, so I loved Silver Chair so so much. And then this book. I suppose I really need to read it again, but the taste of the first read is always in my memory, so I just never can summon up the will to read it…thanks for your thoughts on it, Mari, so I could remember what actually happened in it!

And as to the comments on Narnia in LWW…I always just assumed that the spell placed upon the land kept them isolated from the rest of the world…and that knowledge of the rest of the world had disappeared, pretty much. Of course, 100 years is a pretty short time for that. I would definitely agree that Lewis did a lot of ret-conning and changing his own mythology…but ah well. He didn’t have the foresight to do what Tolkien did and build a mythology over years and years before creating a masterpiece…

And for me, I consider Narnia to be semi-Christian-based so I’m not surprised by the heavy use of Christian themes and beliefs. So Mari, when you mentioned your distaste(hope I’m not being too strong here, but think this is correct) for the idea of a “divine plan”, I simply take this for granted as part of a pseudo-Christian work. It doesn’t glare out at me…of course, being the fact that I am Christian probably doesn’t hurt either!! I guess what I’m trying to say in my long-windedness here, is that many of the religious overtones that are so grating to some seem very natural to me.

@yenny – The recent Narnia sets that I’ve seen in the U.S. have the books in internal chronological, not publication order. I think this ruins the impact of Wardrobe, not to mention focusing the inconsistencies between this book, Wardrobe and Magician’s Nephew, but others disagree – and Magician’s Nephew is definitely an amusing place to start, so, internal chronological order isn’t bad.

My set is from the 1970s and numbers the books in publication order.

I can definitely see the White Witch slamming down the borders, and other people saying, yeah, well, you know, we used to take those summer trips to Narnia for hunting and fishing but then it just got too cold so we gave up ;)

@ClairedeT – I figure that Peter was too busy fighting giants to worry about marriage :) And when he returned to England, well – he never met another girl his age who had been to Narnia (Jill is still distinctly underage in the last book and Polly is of course far older.) Same goes for Edmund.

Fanwanking aside, my guess is that Lewis didn’t get into romances/marriages for his child protagonists for the same reason L. Frank Baum didn’t in his Oz books – they both figured that kids wanted to read about adventures, not romances. That was true about me, certainly, although I don’t know about other kids.

@euphbass – I guess my issue here is that the only culture that we see forcing child marriages is the upper class Calormen culture – even Shasta from the poor fishing village finds this shocking, which gives a sense of “only dark skinned people do this” sense. I do think in this book it’s mitigated by the positive portrayal of other Calormene characters, but it’s still there.

@Sonofthunder – I’m not sure that “distaste” is the correct word here. More “inadequate.” Lewis drops a telling comment that Shasta is used to “hard knocks.” In other words, he hasn’t just been a slave, he’s been beaten – even the unsympathetic Tarkaan lord thinks that Shasta’s owner/father has treated Shasta terribly, which says something. I think Shasta is right; he has had bad luck. Even if this turned out to be good news for Archenland, and eventually Shasta, in the end, I don’t question that his early life was unfortunate, and Aslan’s explanation of “I do not call you unfortunate” because this was all part of a divine plan feels inadequate to me, although it certainly fits in with the book of Job.

Mari@@@@@ 27, thanks for explaining further; think I understand better now what you were getting at!

And as to the publication order of the books…I think I’ve mentioned this previously, but it also grieves me to know that people are reading them starting with Magician’s Nephew! I was talking to a friend from Germany the other day and she was talking about reading them aloud with her boyfriend(lovely idea!!) and they started with Magician’s Nephew, because that’s the order they came in(Yes, I asked!!). Apparently there are German sets that come that way as well. To my chagrin.

This a landmark book in my life. It changed my life forever. My father gave me a copy when I thirteen and at that instant I was hooked on reading and fantasy literature. I also decided to be a writer. I wanted to write a book like this one.

Twenty nine years later I am still reading and writing. Whatever flaws this book has, it helped make me who I am.

Thanks Dad!

Like it or not, some Muslim countries (I’m thinking of Saudi Arabia) are theocracies, have little sympathy for individual freedom, and the aristocracy do have slaves (even today), or at least servants whom they can abuse with impunity. It’s not racist to point out that they suck.

Food for thought. The Calormenes have always struck me not neccesarily as so much of a quasi Islamic society as an evolved Babylon. For one thing one of the first things that leapt out at me when rereading this was all of the references of this or that garden. It’s probably stretching it to link these references to the Hanging Gardens of Babylon, but for whatever reason that’s the first thing that comes to mind, though i suppose the illustrations of Tashban help. So, i suppose does the discription of the Tarkhaans who in a way seems to be more of a throwback in appearances to Chaldean cultures. On a more thematic level setting up Calormene up as the “New Babylon” makes sense when you take into account their role in the Last Battle. The analogy isn’t perfect of course. I can see where people are

coming from on the connections to Islamic culture, the biggest hangup for me on the paralel is, of course, Tash himself. Between the multiple arms and vulture’s head he himself seems to be rooted in some of the darker aspects of Hinduism.

Bits that I love:

Bree’s constant worries- “But what if Talking Horses don’t roll in the grass, wiggle their ears, etc.’ and Hwin’s response- ‘Well, I’ll do it anyway.’

The whole scene between Aravis and Lasraleen.

Corin’s joy at not having to be King. Plus the story about his boxing the Talking Bear who had gone back to Wild Bear habits. Corin climbed up to its lair….and boxed it without a timekeeper for thirty-three rounds.

@gorbag: In which of his book is Lewis approving of the Crusades?

It’s just a story that’s make believe. He borrowed from his own mental models to create this world. Don’t make it into something more than what it is–a fairy tale for children.

Just to be clear, the author doesn’t say that Aravis is Muslim. The Calormenes appear to believe in many gods with the main one being Tash.

Meaning that Aravis is as far from a Muslim as it is possible to be. They are fiercely monotheistic.

@12 and others. It has never bothered me that Tumnus and others did not know of humans during the White Witch’s reign. Presumably the country was isolated in cold (referenced in the horse and his boy by the Tisroc), there was very little trade, contacts with the greater Narnian world would have been few and far between, and ignorance of the outside world would have been great. Much like many oppressive dictatorships today. Once the Pevensies became kings and queens, naturally trade, exploration, and relations with other countries occurred again.