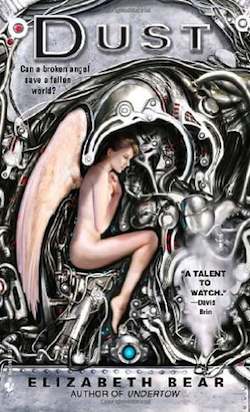

In February, the final book of Elizabeth Bear’s Jacob’s Ladder trilogy was released, completing an ideologically ambitious narrative that explores several familiar SFnal concepts with a fresh and vibrant focus. The three novels—Dust, Chill, and Grail—revolve around the titular Jacob’s Ladder, a generation ship that, as of the opening of Dust, is stranded orbiting a pair of stars which are approaching a catastrophic reaction.

There’s quite a bit more going on in these books than just space opera on a generation ship, though; if anything, they’re deconstructive of the genre itself. Over the course of the trilogy, Bear works in politicking, bioengineering, transhumanism, religion, duty, family, love, trauma and a hefty set of thematic arguments relating to all of those things—plus, what growing up is about. Also, there’s a varied, beautiful spectrum of queer characters and relationships of all types.

Like I said, they’re ambitious.

Spoilers below.

For the purpose of this post—as part of the Queering SFF series—I’m going to have to narrow down my exploration of these books a little, or this could turn into a dissertation. I will at least mention that there’s a whole lot more going on in these books than what I have the room to discuss here, including some of those aforementioned heavy themes, like the treatment of religion/faith in Grail, or the ethics of bioengineering and transhumanism over the entire series. Each of those themes alone is worth an essay.

But on to this discussion, in this particular post.

As has been said by Bear in interviews before (such as this podcast), the original titles of the books were Pinion, Sanction, and Cleave—all words with contradictory meanings, able to be two things at once. (I do sort of wonder who in a marketing department I could yell at for the title-changes, because when considering the thematic arc of the novels and what they seem to have to say, I couldn’t have asked for better and more meaningful titles than those.) I’d like to mention this first, to get the resonances of those words out there in the air while discussing the books themselves, words that are many things at once.

Though the science and the tech are impressive and vividly written, the characters are the driving force in the Jacob’s Ladder books: the Conn family, a tangled and fractured bloodline of rulers and warriors, form the bulk of both protagonists and antagonists, though by the final book the cast has expanded to include the natives of the planet Fortune. There are also the angels, sentient AIs with their own desires and needs, and other characters outside the Conn family, like Mallory the necromancer.

The complex interpersonal relationships include those of family and romance, often both, as the Conns—freed from genetic issues by their sybmionts—intermarried frequently. The role of gender—or lack of a role, as the case may be—in these romances is something I deeply enjoyed; the social definition of gender in the Jacob’s Ladder is a fluid and multi-potential thing, not limited to a simple male/female binary.

Mallory, in particular, is a character whose gender performance is wonderfully written—I don’t see many genderqueer characters in fiction, but Mallory fits. Bear avoids using gendered pronouns for Mallory whenever possible, also, which requires deft writing. During a liaison with Rien in Dust, as they’re negotiating the possibilities of sex between them, Mallory has a good line:

“I don’t like men,” Rien said, though she could not look away for a second from Mallory’s eyes—blacker in the half-light than Rien remembered them from the sun—under the witchy mahogany frizz of bangs.

“How fortunate for me that I’m not one,” Mallory answered, and kissed Rien again. (101)

There is also the ungendered character Head, whose pronoun is “hir,” and characters like Perceval herself, eventual Captain of the Jacob’s Ladder, who is asexual and identifies as a woman. Her falling in love with Rien, and Rien in return with her, is the source of much of the terror, sorrow and joy of these books. Their negotiations, also, are well-handled; as Perceval says when she asks Rien to marry her, “Oh, sex. So take a lover. Don’t be ridiculous. Who wants to marry a martyr?” (332) The ending of Dust is even more heartwrenching because of this discovery of love, as it ends with Rien sacrificing herself so that Perceval can become Captain and integrate the world, saving them all.

However, for those worried about the “lesbian love must sacrifice itself” thing, don’t be. Through Chill and Grail, Perceval fights to find a way to keep her love for Rien alive through memory, and finally, at the end of Grail, they’re reunited when the citizens of the Jacob’s Ladder transcend their biology into beings more like the angels. It’s one of the few unambiguously happy endings in Bear’s books, and the journey to get there makes it all the more emotionally fulfilling.

Additionally, by the time of Grail, Tristen—Perceval’s uncle, one of the oldest living Conns—and Mallory have fallen in together, and their relationship leads to some of the best and most emotional ending lines I’ve read in some while: “We are all we have. And we are so small, and the night is so large.” (330)

The Jacob’s Ladder books are queer in a fully realized, satisfying way; there’s nothing remarkable about the relationships the characters develop or how they identify in the context of the world. It’s normal. This is the best thing, for me, reading science fiction; the possibility that eventually we may live in a world where the gender binary has broken down and relationships are judged on emotion and not bodies. The inclusion of asexuality and genderqueer characters put this series high on my recommended reading list, too, as those particular identities show up somewhat rarely. The fluid simplicity of identity and sexuality in the Jacob’s Ladder books is so very satisfying.

Of course, that’s only one part of the thematic structure of the trilogy—overall, the books are most concerned with growing up, with the journey to becoming an adult, regardless of how old a person actually is. The backdrop for all of the personal journeys of the characters is the literal journey of the Jacob’s Ladder, from a devastated and decrepit earth in the 22nd century (if I remember correctly), to being stranded around a dying pair of stars by sabotage, to the great sacrifice required to propel the ship underway again, to the final destination and the last step of their journey: Fortune, and what happens there when Ariane Conn and Dorcas, a member of an extremist sect, fight to control the destiny of those who have been part of the Jacob’s Ladder. There are explosions, swordfights, and intrigues of all kinds; treachery and betrayal, exacerbated by the seemingly un-killable nature of someone imbued with a symbiont and enough time to make backup plans.

The Jacob’s Ladder trilogy is made of books built on big ideas and big concepts—the nature of what it is to be human, of what it is to love, to sacrifice, and to be a good person despite all pressures in other directions. Aside from all of the deep and thematic bits of its story, though, it’s also a ridiculously beautiful set of books. The epigrams in each are food for thought for days and weeks, the dialogue is crisp and often complex in its nature, hiding as much as it reveals, and the descriptions of the vibrant, lush world are enough to steal a reader’s breath. Bear has wrought a fine trilogy with the Jacob’s Ladder books, and within them a world that treats gender and sexuality nonchalantly, as a background feature that simply doesn’t matter to the characters themselves—because it’s only natural.

I heartily recommend picking these up, whether for their queer content, or simply because of how good they are as SF books, or both. The writing is gorgeous and the action is breath-taking; the big ideas are crunchy food for thought and the characters will stick with you long after you’ve finished reading. Two thumbs up from me for the Jacob’s Ladder trilogy.

Lee Mandelo is a multi-fandom geek with a special love for comics and queer literature. She can be found on Twitter and Livejournal.