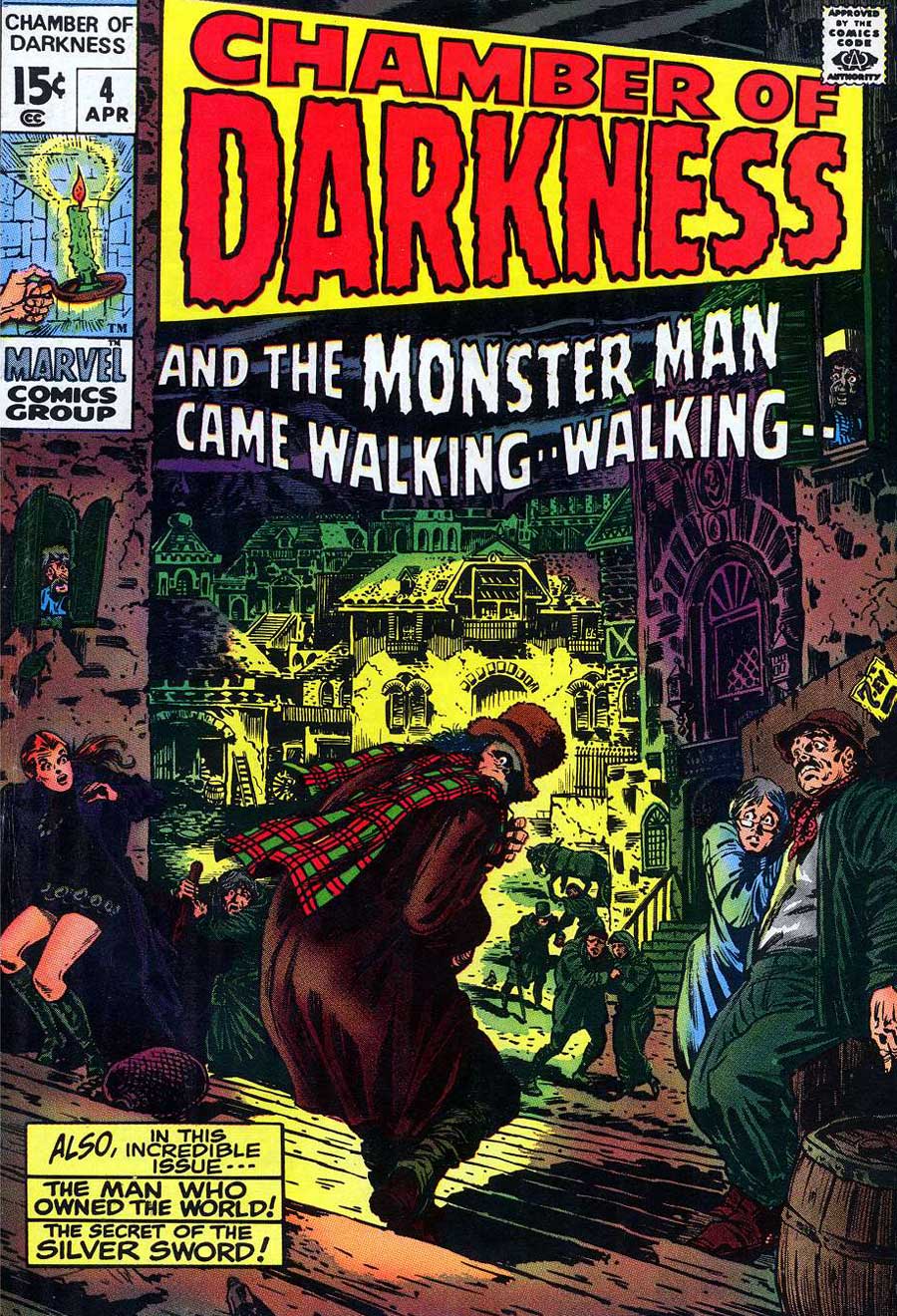

It all began with an unassuming cover, from a Marvel comic called Chamber of Darkness #4, in the spring of 1970. A clash of grim Victoriana and mod fashions, the image on the front of that comic recalled the darker side of Edward Jekyll from Robert Louis Stevenson’s famous novella and featured an ominous caption which read “And the Monster Man Came Walking – Walking – “

But what was more important, perhaps passing unnoticed by the young readers who grabbed that 15-cent issue off the spinner rack at the local corner store, was the small yellow text box in the lower-left hand corner of that cover. “Also, in this incredible issue…” it read, “The Man who Owned the World” and “The Secret of the Silver Sword.”

That last title, odd for a horror comic, is the one that matters. It’s where Conan was born, at least in the pages of Marvel Comics. Readers didn’t realize it at the time. But that’s okay, because neither did the writer or the artist.

As long-time Conan comics writer, and even longer-time comic book historian, Roy Thomas describes in the foreword to volume one of The Barry-Windsor Smith Conan Archives, readers in the late 1960s began bombarding Marvel with letters demanding what they called “sword and sorcery” comics. They wanted four-color versions of J.R.R. Tolkein’s Frodo in Middle-earth. Or Edgar Rice Burrough’s John Carter on Barsoom. Or Robert E. Howard’s Conan in the Hyborian Age. Conan, in particular, was on reader’s minds, as the Lancer series of Conan paperback reprints had hit the shelves in the mid-to-late 1960s, complete with the instantly iconic Frank Frazetta covers.

According to Thomas, who had already established himself as a successful Marvel writer by 1970, Editor-in-Chief Stan Lee was well aware of the reader’s interest in something Conan-like, even if neither he nor Thomas had any experience with the genre. Thomas mentions, in fact, that he had never read more than a few pages of any Robert E. Howard Conan story when Lee asked him to write a memo to Marvel publisher Martin Goodman in an attempt to convince the money-man to license the rights for one of the sword and sorcery characters that was bubbling up in popular culture.

Thomas says that Goodman was persuaded, but wasn’t willing to take much of a financial gamble on an untested genre. At that time, Marvel was a basically a superhero publisher that had evolved out of a monster comic publisher. Guys with swords in some exaggerated fantasy world of the pseudo past was something outside of their realm of experience. But Goodman was willing to offer the tiny sum of $150 per issue to license a character.

Around the same time Thomas was given the green light to pursue a licensed character at a low cost—though in Thomas’s recollection of events, the timeline gets a bit fuzzy—he scripted a short story for Chamber of Darkness #4, for young artist Barry Smith to draw. A story about a muscle bound barbarian king. A story called “The Sword and the Sorcerers” featuring the silver sword alluded to in that tiny yellow box on the cover. Perhaps capturing the anxiety about pursing a Conan-like character for Marvel’s use, Thomas’s story features Starr the Slayer, a clear Conan knock-off, but instead of telling a straightforward tale of barbarian action, the story depicts pulp writer Len Carson, tormented and ultimately killed, by his own fictional creation.

Around the same time Thomas was given the green light to pursue a licensed character at a low cost—though in Thomas’s recollection of events, the timeline gets a bit fuzzy—he scripted a short story for Chamber of Darkness #4, for young artist Barry Smith to draw. A story about a muscle bound barbarian king. A story called “The Sword and the Sorcerers” featuring the silver sword alluded to in that tiny yellow box on the cover. Perhaps capturing the anxiety about pursing a Conan-like character for Marvel’s use, Thomas’s story features Starr the Slayer, a clear Conan knock-off, but instead of telling a straightforward tale of barbarian action, the story depicts pulp writer Len Carson, tormented and ultimately killed, by his own fictional creation.

In reprints of the Starr story, it’s sometimes called a “trial run” for Conan. But it wasn’t. It was a throwaway story, no doubt informed by the background discussions Thomas was having with Lee about the increasing popularity of sword and sorcery characters.

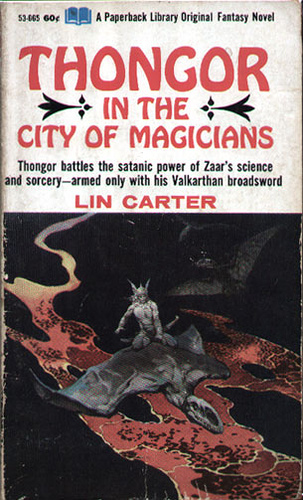

And then there’s this little fact: once Thomas did have approval to pursue a licensed sword and sorcery character, he didn’t approach the Howard estate. He decided to go after Lin Carter instead, and make a play for Thongor.

Thongor is largely forgotten now, but Carter’s creation reached a respectable level of popularity in the 1960s, with six Thongor books released between 1965 and 1970. The barbarian Thongor was a tribute to Howard’s Conan, certainly, and Carter himself was one of the co-editors on the Lancer Conan paperback series, so he was certainly known at the time as an expert on all thing Hyperborian.

As Thomas puts it, “Stan and I had figured that Conan, who after all was in a number of popular paperbacks by now, would undoubtedly be out of our league financially… Lin himself liked comics and liked the idea of Thongor being a Marvel hero.”

As Thomas puts it, “Stan and I had figured that Conan, who after all was in a number of popular paperbacks by now, would undoubtedly be out of our league financially… Lin himself liked comics and liked the idea of Thongor being a Marvel hero.”

But Carter’s agent wanted more than $150 per issue for the then-mighty Thongor of Lemuria. Goodman wouldn’t budge. Negotiations ceased.

With more reader demands rolling in and no sword and sorcery character at Marvel to placate them, other than Starr the Slayer, in his brief, ironic appearance, Thomas took a desperate gamble and sent in a letter to the Howard estate, offering $200 per issue (unauthorized by Goodman) for the use of Conan as a Marvel hero. The Howard estate accepted immediately, to Thomas’s surprise, and he then figured that he had to actually write the comic, not out of any particular love for the character, but because he might owe Marvel some money.

“Now I realized,” says Thomas, “that I had better write at least the first issue or so myself, so that, if Goodman suddenly noticed the difference and wanted his extra $50 back, I could take that sum off my writing fee.” Thus Roy Thomas, who was soon to succeed Stan Lee in the editor-in-chief role, began his career as the longest-running Conan writer of all time, scripting hundreds of issues of barbarian adventures for Marvel.

Yet even with the character licensed and the writer in place, a problem still existed. Who would draw the thing? John Buscema would have been the perfect choice, with his notable disdain for superheroes and his masterful ability to illustrate lush landscapes and hearty heroes. But with $200 per issue going to the Howard estate, Marvel was unwilling to devote one of their highest-paid artists to the project.

Enter Barry Smith (now known as Barry Windsor-Smith) a then 22-year old artist from England who showed up at Marvel comics two years earlier with sample pages that looked like they were drawn by Jack Kirby, or at least someone trying to harness the spirit of Jack Kirby. Smith had been filling in on X-Men and Avengers and doing piecemeal work here and there, but his energetic Kirby-esque page layouts and thick figures would fit Conan the Barbarian just fine. As Smith himself recalled, in a 1998 interview for Comic Book Artist #2, “I believe that Stan wasn’t wholly behind the idea of a Conan comic and, if I recall, he was against putting an important artist on a book that was probably going to tank. Obviously, I was not considered an important artist at that period.”

Smith, now widely considered one of the greatest comic book artists in history, was also the very same artist who had already worked with Thomas on Starr the Slayer the year before. And when it came time to do Conan, Smith gave the Marvel version of Howard’s character a look almost identical to the look sported by Starr in that one issue of Chamber of Darkness, complete with horned helmet and medallion necklace. That’s why Starr the Slayer is labeled, retroactively, a warm-up for Conan, a kind of trial run, even though neither Thomas or Smith knew that at the time.

Smith, now widely considered one of the greatest comic book artists in history, was also the very same artist who had already worked with Thomas on Starr the Slayer the year before. And when it came time to do Conan, Smith gave the Marvel version of Howard’s character a look almost identical to the look sported by Starr in that one issue of Chamber of Darkness, complete with horned helmet and medallion necklace. That’s why Starr the Slayer is labeled, retroactively, a warm-up for Conan, a kind of trial run, even though neither Thomas or Smith knew that at the time.

So when Conan the Barbarian debuted in the fall of 1971, with a cover blurb claiming that it was the character’s “First Time in Comic-Book Form!” the words were technically true, and powerful. That comic book, drawn by Smith and written by quick-Howard-study Thomas, certainly helped spread the Conan gospel to the world. The series, which ran, in one form or another—often with multiple titles coming out monthly—for 26 years at Marvel, defined the sword and sorcery genre in the comic book medium, and led to a rash of imitators, from parodies like Dave Sim’s Cerebus the Aardvark to Sergio Aragones’s Groo the Wanderer to more direct rip-offs like Atlas’s Wulf the Barbarian and DC’s Claw the Unconquered.

A brief postscript: Marvel ended up publishing Thongor comics after all, starting with an appearance in Creatures on the Loose #22 in 1973. The negotiations probably went a bit more smoothly the second time, with a few Conan sales figures thrown in to grease the wheels of bargaining.

Tim Callahan writes about comics for Tor.com, Comic Book Resources, Back Issue magazine, and his own Geniusboy Firemelon blog.