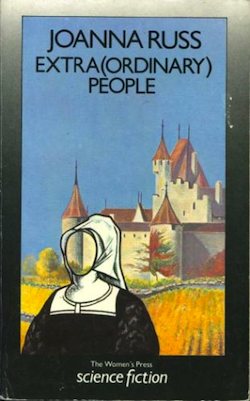

Yesterday we discussed the first half of Extra(ordinary) People, Joanna Russ’s 1984 collection of short fiction. I left off at the end of one of my favorite stories, the very genderqueer tale “The Mystery of the Young Gentleman,” and the potential reading of it as a story, not just about the performativity of gender, but about passing and survival in normative, often dangerous society. Where we continue…:

The frame tale then says that no, the telepathic minority died out without affecting the outside world much at all—but a utopia was established eventually. That leads us to the next story of performativity and gender, “Bodies.”

In contrast, “Bodies” is a different kind of story about the artificial nature of gender binaries in contemporary society, as explored by two people who have been brought back to life in a far-flung utopian future. One was a gay man when he was alive who never managed to have a life as himself; the other was once a woman real-estate broker and writer. The people of the future don’t bring anyone else back after James, the man—it’s too upsetting for them to see the damage that the past’s constructions of identity and norms had wrought. Gender is much more fluid in this future, and so is sexuality; James does not have an easy time adjusting, and neither did the narrator.

“Bodies” is an emotionally complex story about the bonding between James and the narrator, who are both from similar pasts and are therefore incomprehensible in many ways to their communities in the future. James is performing what he believes is expected of him as a gay man; the narrator is trying to make him understand that he can just be what he wants to be, now, here. She does care deeply for him, though she says “this is no love affair.” (113) Instead, they share something more primal: an experience of what it meant to be a woman, or to be a gay man, in our times—not this future, where those things don’t exist in anything resembling the same way, and are not stigmatized in the slightest, not this utopia where the very concept of being beaten on the street will not be understood.

It’s a recursive story that has much more to say about contemporary constructions of gender and sexuality than it does the utopian future, and what it has to say is mostly melancholy and unpleasant. Still, it also leaves room for the hope of change, and the hope that the strictures and the damage may eventually be unwound. It’s a shorter story than those that have come before, by my count, and seems to be doing less also—but what it is doing is intense, and the characters Russ gives us to explore it are neither perfect nor impossibly flawed; they are simply people, damaged and trying to learn who they are in a whole new context of being. It’s all about performance and identity, again, but this time it’s also about the ways in which performance can be integral to identity, not simply something that can be changed or discarded with ease. That provides the counterweight to the utopian futures’ own constructions of being, and shows that they are perhaps not more perfect, just different.

The frame narrative between this story and the next is the child shutting the tutor off, moodily, and turning it back on after some brooding to be told the next tale, “What Did You Do During the Revolution, Grandma?”

“What Did You Do” is one of the strangest of Russ’s stories, unstuck as it is in time and probability, slipping merrily between worlds where probability is less than it is in the narrator’s and then finding out that theirs isn’t perfect either—what’s real, what real is, and what the hell is going on; none of those things are entirely stable, here.

On the surface it’s about the relation of cause and effect and travelling/shifting across worlds with different ratios (which ends up destabilizing the whole damn system). The narrator has just returned from one of these worlds where she was fomenting a revolution dressed up as a (male) arch-demon/faery prince, Issa/Ashmedai, in “Storybook Land” (122), and is telling her lover, the recipient of her letter, all about it. This is a performance of something like theater; the narrator compares it repeatedly to kabuki drama. The characters of Storybook Land are all faintly (or very) preposterous and unreal, so the narrator can do her job with some ease, but eventually Art and Bob (two noblemen) prove a problem. She has to keep them away from a woman they seem intent to rape by pretending to be the only one who can have her. Then she ends up having to have sex with the princess, who is determined to be had by her (in her male persona), and all sorts of bizarre courtly intrigues. Finally, the playacting done and pretty well injured, the narrator gets to come home and finds out that her own world isn’t at the probability center, either. There’s a revolution going, too.

And so it goes. Frankly, “What Did You Do” is great fun to read but is perhaps the most impenetrable of the lot; it’s weird fiction, all right, a bit hallucinatory and filled with narrative flourishes that quite fit the narrator’s style of storytelling in her letter. In the end, it’s not about the revolution at all—just the connection between the lovers, and the letter. The theatrical, comedic performance of (demonic) masculinity just falls away, leaving us with their connection and nothing else important. (The two epigrams, one about war and the other about it too in a different way, present oddly with the story’s end result—being as it is not about the revolution at all, but about two people communicating.)

The frame narrative then begins insisting that it’s the small things that count, “little things, ordinary acts,” and the child doesn’t believe it, so we get the last story, “Everyday Depressions.”

This is the shortest tale in the book, a set of letters from a writer to her cohort and companion Susannah/Susan/etc. about writing a gothic lesbian novel. The two epigrams are both about art/writing: “It’s all science fiction. by Carol Emshwiller” and “Sex Through Paint wall graffito (painted).“

What follows is, to me, one of the most subtly brilliant of Russ’s short stories. The letters, all from the writers’ side, follow the plot development of this hypothetical gothic novel romance between Fanny Goodwood and the Lady Mary of an estate called Bother, or Pemberly (hah!), or a few other appropriate nicknames throughout. (There are familial ties to an “Alice Tiptree” on one woman’s side; that’s the sort of referential play that makes this story go.) It’s a high-drama gothic, and the writers’ deconstruction of it while she builds it (so much metafiction!) is the height of pleasure for me as a reader. The commentary she has to make on the gender roles and the stereotypes of this particular type of fiction, while still playing with the whole concept, is delightful. And of course, it was inspired by the cover of a book that was a gothic was two men on the front, which inspired her to do one with Ladies.

The plot follows the usual paths—a wicked Uncle, a past love that Mary feels guilty over, a worry that their love can’t be, and finally a culmination of joyous union. It’s very dramatic, and very silly, and all together fun to read about, while the writers’ implicit and explicit commentaries are contrarily quite serious. And then we get to the last letter, and the ending.

I have to pause, here, because I’d really just like to quote the entire last two pages of the story, and that’s not on. I will say that it’s perfect, and wise, and is an absolute kicker of an ending for the collection, thematically immense and intense as it has been. This story ties all the rest up, perhaps not neatly but well, with what the narrator—who is likely to be Russ in the way that Esther of On Strike Against God was a bit of Russ—has to say about storytelling, aging, and the world at large.

So, how about just a little, and then the last page of the frame narrative to tie it all together:

“Last week a frosh wombun (wumyn? wymeen?) came up to me while the other twenty-year-olds were chasing Frisbees on the University grass, playing and sporting with their brand-new adult bodies, and said, ‘O Teachur, what will save the world?’ and I said, ‘I don’t know.’

But that is too grim.”

Which is followed, a page later, by the last of the frame narrative of the child and their robot tutor.

“‘All right,’ said the schookid. ‘This is the last time and you’d better tell the truth.’

‘Is that the way the world was saved?‘

The tutor said, ‘What makes you think the world’s ever been saved?’

But that’s too grim.

&c.”

The concluding lines of “Everyday Depressions” are about living life while there is time, and middle-aged tolerance, and finally, “P.S. Nah, I won’t write the silly book. P.P.S. and on.”

So, what’s it all mean? Well, when the narrator tells us/Susannah that she has some profound truths about life, they’re all questions. The meaning is in the living, not in the answering. The world might not have been saved, and might not be saved—what is saving, anyway?—but there are loves, and there are lives. Those lives are built around identities and performances, masks that are real and masks that aren’t—but they’re all lives, and they’re all valuable.

Discussions of performativity often run the risk of sounding dismissive of the gender/sexuality paradigms that are being discussed as performances, if the discussion isn’t careful to qualify that just because they’re performed and not innate doesn’t make them any less real or valuable. “Everyday Depressions” is that clarification about the value of living, if you have the time to do it, and of self in the world at large. It’s also about stories, and the way that stories structure our ideas of identity and performance—which is, really, sort of what Extra(ordinary) People is all about as a whole. It’s a subtle book in many ways, but a profound one in all; as with complex novels like The Two of Them, talking about it can become a confusing mire of analysis and adoration without a clear way to tie things off and escape.

But, that word is the one I’d like to close on: profound. It may take me years to fully engage with Extra(ordinary) People, and thirty more readings, but I’m willing to put the time in. These posts are my reactions where I stand now as a reader of Russ. It’s hardly over; stories are meant to be read and read and read again to understand them truly. After all, the closing lines of the whole thing are, again:

“‘What makes you think the world’s ever been saved?’

But that’s too grim.

&c.”

*

The next book in Russ’s bibliography is a short chapbook of feminist essays on things like work-division, roles, and sexuality: Magic Mommas, Trembling Sisters, Puritans & Perverts (1985).

Lee Mandelo is a writer, critic and occasional editor whose primary fields of interest are speculative fiction and queer literature, especially when the two coincide. Also, comics. She can be found on Twitter or her website.