I’m not gonna lie to you: I like Starship Troopers, the movie, and pretty much always have. I know many of you don’t. For those of you, I’m going to share my five secrets to enjoying Starship Troopers, the film, here in 2012.

1. Separate the movie from the novel. Here’s how I do it: I think to myself, wow, there’s a terrific novel named Starship Troopers, written by Robert Heinlein, and there’s a unrelated movie called Starship Troopers, written by Ed Neumier and directed by Paul Verhoeven! What a coincidence! There you go. It’s just that easy.

And you say, but—and I say, look, here’s a simple rule. When should you expect Hollywood to make a faithful film adaption of a science fiction novel? Answer: Never. Speaking from my two decades of experience as a professional film critic and observer of the industry, I can tell you that Hollywood does not option books to make movies exactly like the books. They option books to (variously, and among other things) take advantage of existing title/author awareness, to be a hedge against failure—i.e., this basic idea should work as a movie because it’s already worked as a novel—and to strip mine the work for story elements that align with the film makers’ notion of what gets butts into theater seats.

I know many of you want to register a complaint at this point, regarding what film makers should do. Your complaint is noted and as an author of a science fiction novel currently optioned for a film, I am not unsympathetic. I am not talking about what film makers should do, I’m talking about what they actually do. You want to live in a world where film makers take books you love and cherish them and make them into exactly the film version you’ve always imagined in the theater of your brain. You’d probably also like to live in a world where donuts strengthen your abs and make your hair shiny and glossy. And maybe one day donuts will do that. They don’t now.

(Also submitted for your consideration: Authors and their reputations may still benefit even if film versions of their work have almost nothing to do with the originals. See: Philip K. Dick.)

2. Realize you’re watching a Paul Verhoeven film. This is what I wrote about Paul Verhoeven in 1997, when I first reviewed Starship Troopers:

Paul Verhoeven is a director who can give you everything you want in a movie, as long as you want too much of it. This isn’t a criticism of Verhoeven. It’s just a fact. Paul Verhoeven makes movies like tuberculosis patients make fever dreams: vivid, disjointed, with all the human emotions pumped up so far that they bleed into each other like a swirl. A lot of people confuse it for camp, but Verhoeven isn’t out there, winking to the audience. He’s as serious as a heart attack.

It was true then; it’s true now. Verhoeven’s visual and aesthetic sense is narcotic. It’s not intended to be realistic, it’s intended to arouse, in all the various senses of the word.

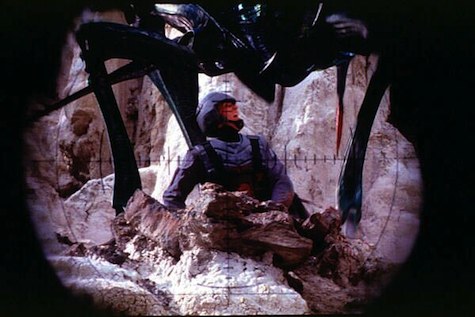

Starship Troopers certainly does that. Whatever else it is, it’s an arousing film: It features a young, hot cast clearly selected more for their visual appeal than their acting chops, lets you linger on their beauty and youth and then tosses those pretty young things into the abattoir, and it’s no surprise that slaughter is also arousing. Verhoeven, being Verhoeven, is perfectly happy to have the same neural pathways that you used to gaze on naked young bodies in a group shower send along the images of those bodies being chopped into steaks by 12-foot-high semi-intelligent bugs. He wants you to have the cognitive dissonance of being as turned on by their destruction as you were by their youthful hotness, whether you consciously register it as cognitive dissonance or not.

3. Recognize the film is a product of its time. The film came out in 1997, the era of Friends and Melrose Place and Beverly Hill 90210. It’s also the pre-bubble Internet 1.0, in which you could be 25 and a stock option millionaire and also be under the impression that you had somehow earned that luck, rather than just being in the right place at the right time. It was a great time to be young and clueless in America.

At this point it’s worth knowing that Paul Verhoeven’s childhood took place in the middle of World War II. His home (in The Hague, Netherlands) was near a German missile base, which was repeatedly bombed by the allies. So at a young age Verhoeven got to see more than his fair share of war-related death, violence and destruction. This fact (along with his own sardonic nature) clearly found its way into his film work.

Now, imagine you’re a director who spent his youth ducking bombs, and you’re dropped into the easy, heedless prosperity of the American 1990s. You’re making a film about young people going to war, aimed at an audience of young people who are under the impression (as young people so often are) that the way things are now is the way they will always be. What are you going to tell them?

You’re going to tell them what Starship Troopers tells its characters (and its audience): Kid, you have absolutely no idea how bad it can get. They didn’t. We didn’t.

4. Notice the film resonates today. In 1997, we hadn’t had 9/11, two middle east wars that have gone on for a decade with their concomitant death and mutilation among a generation of soldiers and citizens, an era of government encroachment of civil liberties excused because “we’re at war,” a grinding economic downturn and a “for us or against us” sensibility that spilled out of foreign relations and into our domestic political discourse (Clinton’s impeachment in the 90s looks almost quaint these days).

(This is not an attempt to finger-point at George Bush or Republicans, incidentally. I strongly believe that if Al Gore had been in office on 9/11 we still would have gone to war in Afghanistan and young American men and women would still have died; our economy would still have suffered a shock; the nation’s political discourse would still likely have become strident and possibly toxic; we’d still have confronted questions of where and when liberties take a back seat to security. You would still have to take off your shoes to get on an airplane. The differences there would have been in degree, not kind, and would have in any event been substantial enough for what we’re talking about here.)

I’m not going to make an argument that Starship Troopers is in any way a realistic look at what war is, either in our time or in its own. Anyone with even the slightest of inkling about military strategy or tactics looks at the thing and throws their hands up in despair (followed quickly by biologists, once they get a load of the bugs spewing missiles into orbital space via their sphincters). Beyond that, it’s a commercial science fiction action film, in which what would be realistic is going to take a back seat to what is going to be awesome to watch while you’re shoveling popcorn down your gullet.

What I am going to argue, however, is that as a war fable—a dark science fictional fairy tale where young people are thrown into a crucible and only some of them make it out alive—it’s reasonably effective. It’s more effective today than in 1997 because as a nation we know (or at the very least have been reminded once more) what happens when we decide to go to war, and as a result we chuck young people into the grinder. The previously-amusing “Do You Want To Know More?” interstitials are no less amusing after a decade of clicking through the Internet to get one’s news, but they do seem rather less hyperbolic. The men and women being chopped up by the enemy take on a slightly different meaning when some 21-year-olds who went to war came home in coffins and others walk around with prosthetics that are awesome and state of the art, but still not their original flesh and bone. The funhouse mirror of Starship Troopers has gotten a little less warped over time.

Of course, neither Verhoeven nor his screenwriter Neumier could have known any of this would happen; the film isn’t prophetic and it would be foolish to suggest it was. Verhoeven doesn’t get credit for being a Cassandra. What it had, however, was an awareness of what war actually does, grounded in Verhoeven’s own experiences. Verhoeven amped it up, for his own personal aesthetic purposes and because at the end of the day his movie needed to make money if he was going to get his next job (his next job was Hollow Man, unfortunately). But it’s there. After the decade we’ve had, it looks smarter, and slightly less over-the-top, than it did when it was made.

(As extra credit, watch Verhoeven’s Dutch-language films about World War II: Soldier of Orange and Black Book. They are excellent, and also illuminating regarding who Verhoeven is as a director.)

5. Ignore the fact that the direct-to-video sequels exist. Because, wow. They’re awful. And not directed by Verhoeven. While you’re at it, you’re allowed to be skeptical about the reported intended remake of the film, currently scheduled for 2014. It’s no more likely to be based on the original novel as Verhoeven’s film was, and if the directorial succession of the upcoming Total Recall remake (to be directed by Len Wiseman, of the competent but joyless Underworld films) is any indication, the narcotic fever dream that is Verhoeven’s directorial aesthetic will be replaced by one that’s probably going to be a lot less interesting to watch.

John Scalzi‘s first published novel Old Man’s War was a finalist for the Hugo Award, took first place in the Tor.com Best of the Decade Reader’s Poll, and won him 2006’s John W. Campbell Award for Best New Writer; since then, he has published six more novels. Your Hate Mail Will Be Graded: A Decade of Whatever, 1998-2008, a collection of essays from his popular weblog The Whatever, won the Hugo for Best Related Work in 2009. He is currently serving as president of the Science Fiction Writers of America.