My experience when reading most articles in The New Yorker is usually one of rapt contradiction. Whether it’s a Susan Orlean essay on the history of mules, a piece about Internet dating, or an undercover exposé of the Michelin Guide, I often get the sense that the writer is sort of squinting sideways at the subject in an effort to render it interesting and intelligently amusing. This isn’t to say the articles aren’t great, just that the erudite tone makes me sometimes think they’re sort of kidding.

To put it another way, I sometimes feel that articles in The New Yorker are written to transform the reader into their mascot, the dandy Eustace Tilley. The prose feels like you’re holding up a smarty-pants monocle to check out a butterfly.

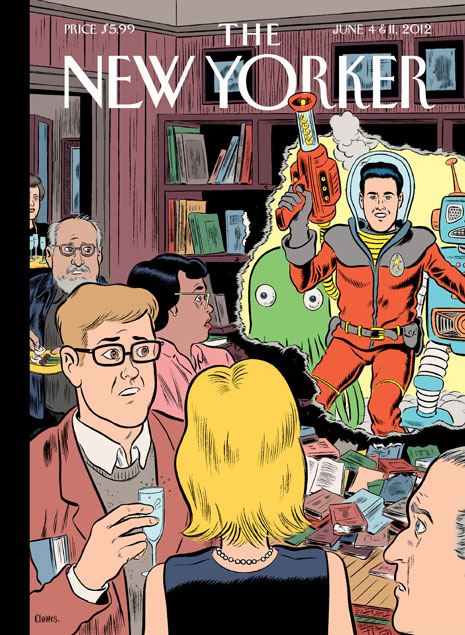

With the debut of The New Yorker’s first ever “Science Fiction Issue” the periodical of serious culture is holding up its monocle to our favorite genre. The results? As the Doctor might say, “Highbrow culture likes science fiction now. Science fiction is cool.” But do they really?

There’s a ton of fiction in the Science Fiction Issue of The New Yorker but, not surprisingly, the pieces that might appeal to more hardcore “Sci-Fi” fans are the non-fiction ones. There’s a beautiful reprint of a 1973 article from Anthony Burgess in which he attempts to explain just what he was thinking when he wrote A Clockwork Orange. This essay has a startling amount of honesty, starting with the revelation that Burgess overheard the phrase “clockwork orange” uttered by a man in a pub and the story came to him from there. He also makes some nice jabs at the importance of writerly thoughts in general declaring the novelist trade “harmless,” and asserting that Shakespeare isn’t really taken seriously as “serious thinker.”

But the contemporary essays commissioned specifically for this issue will make a lot of geeks tear up a little bit. From Margaret Atwood’s essay “The Spider Women” to Karen Russell’s “Quests,” the affirmations of why it’s important to get into fiction, which as Atwood says is “very made up,” are touching and true. Russell’s essay will hit home with the 30-somethings who grew up on reading programs which rewarded young children with free pizza. In “Quests” the author describes the Read It! Program, in which most of her free pizza was won through reading Terry Brooks’s Sword of Shannara series. When mocked for her reading choices, she heartbreakingly describes filling in the names of other mainstream books on the ReadIt! chart instead. But ultimately, Karen Russell declares, “The Elfstones is so much better than Pride and Prejudice” before wishing well the geeky “children of the future.”

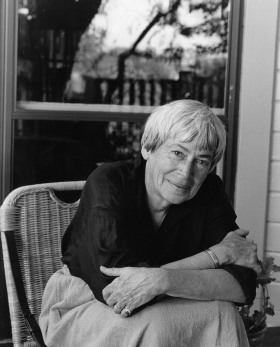

Ursula K. Le Guin turns slightly more serious with a great piece about the so-called “Golden Age” of science fiction, a time in which Playboy accepted one of her stories for publication and then freaked out a little when they found out she was a woman. The eventual byline read, “It is commonly suspected that the writings of U.K. Le Guin are not actually written by U.K Le Guin, but by another person of the same name.” Her observations about some of the conservatism in SFWA’s early days are insightful and fascinating and also serve to remind you just how essential Le Guin is to the community. Meanwhile, China Mieville writes an e-mail back in time to a “young science fiction” fan who seems to be himself. This personal history is a cute way of both confessing his influences and wearing them proudly. It also contains the wonderful phrase “the vertigo of knowing something a protagonist doesn’t.”

Zombie crossover author Colson Whitehead appropriately writes about all the things he learned from B-movies as a child, while William Gibson swoons about the rocket-like design of a bygone Oldsmobile. Ray Bradbury is in there, too.

A perhaps hotter non-fiction piece in this issue all about Community and Doctor Who. As io9 previously pointed out, writer Emily Nussbaum kind of implies the current version of Doctor Who differs from its 20th century forebearer mostly because it’s more literary and concerned with mythological archetypes and character relationships. Though some of this analysis feels a little off and bit reductive to me, it is nice to see Who being written about fondly in The New Yorker. However, the best non-fiction piece in the whole issue is definitely “The Cosmic Menagerie” from Laura Miller, an essay that researches the history of fictional aliens. This article references The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction, and points out the notion of non-terrestrial adaptations are mostly the result of a post-Darwin world.

But what about the science fiction in the science fiction issue? Well, here’s where The New Yorker remains staunchly The New Yorker. All of the short stories are written by awesome people, with special attention to Jennifer Egan’s Twitter-ed story “Black Box.” But none of them are actually science fiction or fantasy writers. Now, I obviously love literary crossover authors who can identify as both, and as Ursula K. Le Guin points out in the “Golden Age” essay, people like Michael Chabon have supposedly helped to destroy the gates separating the genre ghettos. But if this were true, why not have China Mieville write a short story for the science fiction issue? Or Charlie Jane Anders? Or winner of this year’s Best Novel Nebula Award Jo Walton? Or Lev Grossman? Or Paul Park?

Again, it’s not that the fiction in here is bad at all (I particularly love the Jonathan Lethem story about the Internet inside the Internet); it simply doesn’t seem to be doing what it says on the cover. Folks within the genre community are becoming more and more enthusiastic about mainstream literary folks by celebrating the crossover and sharing “regular” literary novels with their geeky friends. One of the aims of a column like this one is to get science fiction readers turned on to books they might not otherwise read. (China Mieville mentions this is a problem in his New Yorker essay.) But the lack of inclusion of an actual honest-to-goodness science fiction (or fantasy!) writer made me feel like we weren’t getting a fair shake.

In the end, when Eustace Tilley holds up his monocle to a rocketship, the analysis is awesome, readable, and makes you feel smarter. But Eustace Tilley can sadly, not build a convincing rocketship. At least not this time.

Ryan Britt is the staff writer for Tor.com.