Season 5, Episodes 6 and 7: “Christmas Carol”/“Emily”

Original Airdates: December 7 and December 14, 1997.

Was there ever a character so abused by her writers as Dana Scully? In tribute to the character’s fortitude, the Internet used to call her Saint Scully—overlooking, of course, the fact that saints tend to be dead. Scully’s not dead, but Scully does suffer, over and over, as though the show’s writers believe that the character couldn’t exist without depression dogging her heels. Just a handful of episodes after she survives cancer, along come “Christmas Carol” and “Emily,” a bleak pair with angst in mind.

“Christmas Carol” is a rare all-Scully episode, an episode in which Mulder appears only briefly. She’s gone home for the holidays, where home is the naval base where her brother Bill and his very pregnant wife live. In the Scully family setting, our Scully becomes Dana, the troubled daughter and distant sister. No one discusses the cancer directly, but they all look at her under hooded eyes, walk around her carefully as she stares into space. Except it’s not cancer that’s haunting Scully, but loss. Loss of her sister, Melissa, and loss of her own ability to conceive a child.

Because right! Remember in “Memento Mori,” when Mulder found out that Scully was barren and then slipped some of her ova into his pocket, and then remember how he didn’t say anything to her? Well someone said something, at some point, because she knows, and in tears she admits at much to her mother. “I just never realized how much I wanted it until I couldn’t have it,” she says, a line that is as tragic as it is troubling, coming as it does after her sister-in-law’s enthusiastic speech about her own pregnancy: “I can’t help but think that life before now was somehow less!”

Although it’s easy to criticize this juxtaposition—are we seriously going to hinge a plot on Scully needing a child to feel more complete, like as a woman?—I think it’s important to give the writers credit, here. The X-Files is a show about what it is we do to make up for what’s missing, and what’s missing is what drives these episodes. Scully’s twin mournings (for Melissa, for her potential-motherhood) are reminiscent of Mulder’s (for Samantha, for his childhood), and her grief proves as powerful as his. Melissa, in fact, acts as the episode’s catalyst—Scully receives a phone call from someone who sounds just like her, and a trace on the call leads to a crime scene, a local woman who has committed suicide.

Spooked by the call, Scully acts more like Mulder than herself, pushing at the edges of the case until she’s gathered enough evidence to suspect that the suicide might in fact be a murder. It’s a lot of fun to see Scully in single-investigator mode, working with a local cop and overriding a dubious medical examiner. Gillian Anderson does great work here, her voice low and insistent as she convinces these men that her theories are valid, and they are, and there was a murder, and there’s something else, too: the deceased woman’s daughter, Emily, whose DNA seems to match Melissa’s.

The fact that Scully even bothers to have the results of Melissa’s DNA test sent to her is one of the episode’s finest strokes. Although she at first refuses to involve Mulder in her hunch—she calls him, once, but hangs up without speaking—she now knows better than to dismiss something unexplainable, like those mysterious phone calls, like the funny feeling she gets when she sees Emily standing in the hallway, like the dreams she’s having, the fuzzy-edged ones about her childhood and her sister and mortality.

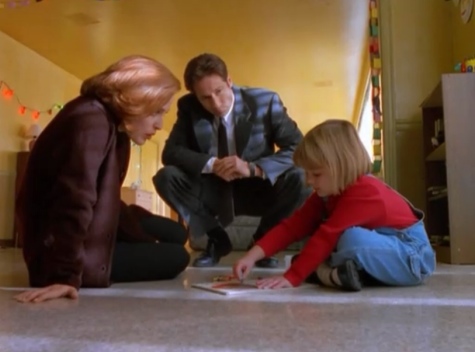

Like Mulder, Scully finds that no one believes her. Her mother and brother dismiss her theories about Melissa running off to have a secret baby, and a social worker tells her that her application to adopt Emily is likely to be denied. Emily, it turns out, is a very sick child, in need of regular medical attention for a rare and incurable blood disorder. She’s in a double-blind trial led by a creepy doctor named Calderon, which frankly is my favorite way to get medical attention for a child. For her part, Emily seems simply tolerant of Scully, staring at the cross around Scully’s neck until Scully gives it to her, a gesture both beautiful and ominous.

On its way out the door, “Christmas Carol” trips over one final plot contrivance, putting an end to the episode’s sloppy strength. According to The Lab, Emily is Scully’s child, and you can insert your own dun-dun-dun here. Or just wait for “Emily”’s cold open, Scully in a gown walking through a desert, ashes to ashes and a voiceover and the cross necklace on the ground. Where “Christmas Carol” was the story of one woman’s attempt to cope with loss, “Emily” is the story of the writers trying super-hard to embed the loss into the mythology.

The result is confusing and thorny, and so is Mulder. At Scully’s request, he flies out to be a character witness in her adoption hearing. Before they meet with the judge, Mulder tells her that he plans to share some evidence with the judge that he believes will otherwise be used against Scully. He then does not tell her what this evidence is? But waits until they’re in the judge’s chambers to say that during her abduction, Scully was subjected to experiments during which her ova were extracted. Back in “Memento Mori,” Mulder’s silence seemed like protective maneuver. Now it seems unnecessarily cruel. Scully’s surprise during the hearing is not at learning this information for the first time—we know that she knows, because she told us so back in “Christmas Carol”—but likely it’s in knowing, suddenly, that Mulder knew. And chose not to say anything. And then chose to say something. In front of someone else.

After that, we’re off to the mytharc races, and “Emily” gets twisted. It becomes clear that Emily is being pursued by some shapeshifters, it becomes clear that Dr. Calderon is a clone (although possibly he does not know this). Less clear is what Emily is—in the hospital she bleeds the green blood of the hybrids, so it’s possible that Calderon’s treatments were turning her into a full hybrid, or that the treatments were meant to fix a botched experiment. Mulder roughs up the Calderon clone, which is fun, then finds his way to a nursing home where the lady patients are apparently being used to incubate hybrids created using pilfered Scully ova. He scoops up some evidence just before the shapeshifters arrive with their super-strength and magical ability to scrub the venue of evidence.

As Emily’s death looms large and inevitable, Mulder attempts to stay with Scully by her bedside, to offer clunky words of comfort along the lines of, this child was never meant to be. But Scully sends him away—a come-uppance, perhaps, for not sharing what he knew about her body, back when—and Mulder is left alone in the hallway with the vials he swiped from the nursing home. A shot of Scully lying next to Emily fades heavy-handedly into a shot of a stained glass window depicting the Virgin and Child, and Scully cries out, in case you missed it: “Who are the men who would create a life whose only hope was to die?”

Only the parallel falls flat, as Emily is no Christ child. If you stretch, you could say that Emily Saves in that she inspires Scully to continue the quest, but that’s a hell of a distance to go for some stained glass. When Scully opens the coffin with the intent to use her daughter as evidence of “what they did,” the body is gone and the coffin is filled with sand. On top is her necklace, left behind as it was once before. “She found me,” says Scully. “So that you could save her,” says Mulder. Because the cross is borne not by this kid we knew briefly, but by our agents, and their struggle. Suffering isn’t the only way to claim redemption, but it certainly is a wonderful way to look like a saint.

Meghan Deans called from beyond the grave to tell you that. She Tumbls and is @meghandrrns.