Good story anthologies aren’t a ramshackle bunch of pieces crammed in any order—like CD albums, there should be a flow, a greater focus beyond the individual stories. These anthologies conduct conversations inside of them: selections that tease, question, argue back and forth with each other, as well as tie together key themes and concepts. Steampunk III: Steampunk Revolution, moreso than the previous volumes in Tachyon Publications’ well-known retrofuturist series, demonstrates the power of a well-orchestrated collection.

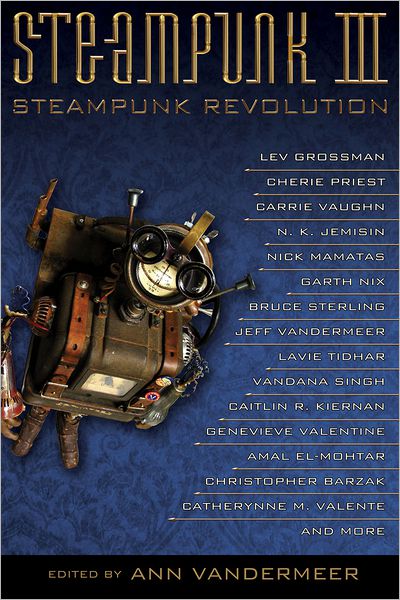

Steampunk has proven to be particularly popular in short form, and for round three, Ann Vandermeer acts as the sole editor to select from the subgenre’s rich offerings. Full disclosure here: Ann is one of our newest additions to the short story acquisitions staff on Tor.com, and the introduction to this anthology was also featured here on Tor as part of our recent Steampunk Week. So I already knew a bit about what to expect when the book arrived.

What distinguishes this volume from the previous two is its sharpened sociopolitical focus. Namely, how can literature instigate revolution? Is that even possible anymore? Many old-school methods of communication to the masses aren’t as effective in our global, digital era. Twitter can organize better than handing out radical pamphlets on the street. TV shows and websites alert us to social causes faster than books written in the vein of Charles Dickens or Victor Hugo. Even pizza can be ordered from across the globe to support another country’s protest. So how can steampunk play a part in social change? Ann argues in her introduction: “In the Steampunk context, it means to examine our relationship with technology, with each other, and with the world around us. And by doing that through the lens of Steampunk, it allows our imaginations to take off. Let’s use creative play to look at creation, invention.”

This collection addresses the dynamic facets of revolution: industrial, political, social, and historical. Not all of these stories are about the flash-and-bang, the anarchist bomb, the topping of statues. Instead, revolution is framed as acts of personal action in the face of social pressure, for good or for ill, which are possible because of that world’s innovative technology.

First off, Steampunk Revolution is dense. Not that it was hard to read, but each story seemed to demand time to sit and process. I normally zip through anthologies, but I definitely had to slow down for this one. Most of the selections are reprints from big names in SF/F: Lev Grossman, Catherynne M. Valente, Bruce Sterling, Jeff Vandermeer, Garth Nix, Cherie Priest, Genevieve Valentine, N.K. Jemisin, and Caitlin R. Kiernan to name a few. The two original pieces, however, are absolutely stunning, which I’ll mention later.

The flow of the book starts off with the most “quickly identifiable” steampunk stories—brimming with pulpy escapades, populated by quirky characters, and dripping with local flavor. Carrie Vaughn’s “Harry and Marlowe and the Talisman of the Cult of Egil” reads like an Indiana Jones homage starring a lady archeologist. Cherie Priest gives her trademark American steampunk stamp to her frontier tale “Addison Howell and the Clockroach.” Paolo Chikiamco’s “On Wooden Wings” explores the cultural differences between two very different students at a scientific and engineering academy in the Philippines (extra brownie points go to the fact that neither of them is English and that the cultural divide isn’t between purely European and non-European perspectives).

The collection then takes a somber turn with stories that explore technology and loss, nostalgic ruin, and salvaging oneself after disaster. A couple of my favorites out of the darker steampunk selections were the elegant vignettes of a wandering circus troupe in Genevieve Valentine’s “Study, for Piano Solo,” and the period-perfect, first-person narrated “Arbeitskraft” by Nick Mamatas, where Friedrich Engels attempts to instigate class revolution while working as a labor organizer for the city’s cyborg matchstick girls.

The story that took me completely by surprise with its effectiveness is Malissa Kent’s “The Heart Is the Matter,” which is also her first publication. After reading Kent’s skillful narration that leads to the story’s literally heart-wrenching conclusion, I look forward to seeing much more from her in the future. Vandana Singh’s “A Handful of Rice,” the other original piece in this anthology, conveys Indian culture viscerally without auto-exotifying it to the non-Indian reader, and I especially appreciate how the relationship between the protagonist and antagonist in this story echoes the importance of male friendship in India’s classical tales.

A few fun gems lighten the heavy load. Lavie Tidhar offers a nonsensical pastiche of 19th century literary tropes in “The Stoker Memorandum.” The most hilarious character award, however, goes to the titular eccentric inventor in J.Y. Yang’s “Captain Bells and the Sovereign State of Discordia.” I was also glad that N.K. Jemisin’s “The Effluent Engine,” about a black lesbian spy in New Orleans, was selected for this collection.

The final story is from one of the first writers of modern steampunk, Bruce Sterling. His entry “White Fungus” is appropriate to the volume and yet also feels like a jarring outlier. A post-apocalyptic, near-future piece about rebuilding society? How can that work in a steampunk anthology? Well, moving across time and space to explore all the variants of steampunk, the volume’s conclusion is finally presented—that today’s innovation, individual action, and imagination about the past directly influences how we determine our future.

The nonfiction section further emphasizes this sentiment with four essays that express a mix of critical concern and delight about the progression of the genre. Amal El-Mohtar did an updated version of her rallying cry “Towards a Steampunk Without Steam” that she first wrote for Tor.com in 2010; two years later, however, she now expresses a more cautionary form of hope. Jaymee Goh, Magpie Killjoy and Austin Sirkin contribute more enthusiastic perspectives, advocating for a greater appreciation of the current progressive themes seen in steampunk. The nonfiction pieces are a heavy-handed endcap: yes, there is more to steampunk than just the pretties. Additionally, a drawback in this nonfiction section is how much emphasis it places on steampunk outside of the speculative word, which leads me to ponder the question stated in the intro once more: how relevant is steampunk fiction to action in today’s world?

That criticism aside, though, the collection was immediately engaging, thorough in its editorial selection, and a must-have for any fan of the subgenre. Despite the boldness in taking a stance about the meaning of art in today’s culture, Steampunk Revolution’s strength does not lie in its agenda-pushing. Instead, this volume showcases quality fiction that can be enjoyed long after the passionate battle-cries have faded away.

Ay-leen the Peacemaker has never lived through a revolution, though her parents did. This probably explains a lot about her. She’s the editor of Beyond Victoriana, writes academic things, and tweets.