Georgette Heyer wrote The Corinthian a few months after the tragic death of her brother-in-law, a close friend, in one of the early battles of World War II, and under the terrible fear that her husband would soon be following his brother into battle, and that her own brothers would not survive the war. She worried, too, about other family friends, and feared that the war (with its paper rationing, which limited book sales) would make her finances, always straitened, worse than ever. She could not focus, she told her agent, on the book she was supposed to finish (a detective story that would eventually turn into Envious Casca) and for once, she avoided a professional commitment that would earn her money, for a book she could turn to for pure escape. Partly to avoid the need of doing extensive research, and partly to use a historical period that also faced the prospect of war on the European continent, she turned to a period she had already researched in depth for three previous novels: The Regency.

In the process, she accidentally created a genre: The Corinthian, a piece of improbable froth, is the first of her classic Regency romances, the one that would set the tone for her later works, which in turn would spark multiple other works from authors eager to work in the world she created.

The Corinthian begins with a family scene tingling with nastiness. Sir Richard Wyndham, a baronet from a very respectable family, receives a rather unwanted visit from his mother, sister and brother-in-law, two of whom wish to remind him of his duty to marry Melissa Brandon. The third, brother-in-law George, notes truthfully that Melissa is an iceberg with several questionable relations. Nonetheless, Sir Richard, urged to duty, visits Melissa and speaks with her about marriage. The conversation is hilarious for readers, if thoroughly chilling for Richard, as his bride outlines her feelings on love (it’s a bad idea) and makes it clear that she is marrying him for money and convenience. The idea so depresses him that he becomes incredibly drunk and meets Pen Creed, who just happens to be climbing out of a window, as one does.

Pen, dressed up as a boy, is climbing out of the window thanks to family problems of her own: Her family is pressuring her to marry a cousin who somewhat resembles a fish in order to keep her money in the family. As various Austen books and other historical records confirm, this sort of motive was common among the British upper middle classes and aristocracy of the period.

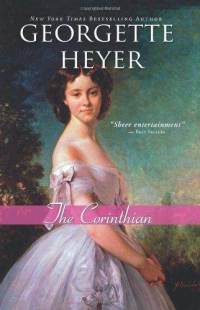

(Incidentally, this makes the current cover image for The Corinthian, shown above, hands down the most inappropriate cover image for a Heyer novel yet—it’s not just that the dress is of completely the wrong period, but, and this is key, it’s a dress, the very thing Pen is escaping. Oh well; I’m assuming Sourcebooks didn’t have access to a portrait of a Regency crossdresser or the funds to commission one. Moving on.)

Richard decides that it would be a very good idea to take Pen, still pretending to be a boy, out to the countryside and to a childhood sweetheart she has not seen in five years. Those of you who have gotten very drunk will understand his reasoning. Those of you who have never been that drunk should just recognize at this point that all sorts of things sound reasonable after enough liquor. It’s the sort of truth Heyer definitely understood.

After this things get more than a bit complicated, what with a stolen necklace, a fake necklace, thieves, a murder, a pair of decidedly silly lovers, Pen’s unwanted relatives, and various people connected with the law investigating the murder and the events leading up to it. Don’t feel too sorry for the murder victim—as Sir Richard says later, “Your dislike was shared by most of his acquaintance, ma’am.” Indeed, the closest thing the victim has to a friend in the novel—and I use the word friend in the loosest possible sense—is more interested in an upcoming elopement and in Pen’s shocking behavior than in his “friend’s” death.

And oh, yes, Pen’s shocking behavior. Unlike Leonie and Prudence before her, Pen is not the most convincing of boys. Oh, she convinces casual strangers she meets on the stagecoach, and a few criminals, but several characters, including Richard, either guess that she’s a girl almost immediately, or guess that she is a girl without even seeing her. And by the end of the book, several characters are aware that Pen has been merrily travelling around the country without—gasp—a single female chaperone or even a maid—gasp gasp—which means, of course, that Pen and Richard must marry for the sake of propriety, a slightly problematic situation for two people who ran away from London to avoid propriety in the first place. For those of you still refusing to be shocked, bear in mind that this is set in the same time period where the choice of a silly sixteen year old girl to enjoy some premarital sex and fun in London is almost enough to doom not just her, but her entire family to social ruin, and everyone agrees with this.

To make matters worse, because this is a comedy, Misunderstandings Abound. Fortunately, because this is a comedy, Happy Endings Abound as well. And interestingly enough, the happy ending for the main pair comes about only when both choose to decidedly flaunt all rules of propriety completely—on an open road, no less. (I envision certain Austen characters falling over in shock.)

As I’ve previously noted, the elements that created The Corinthian had already appeared in earlier works: the Regency setting, the debonair hero fixated on clothing, the cross dressing heroine, the Regency phrases, the focus on proper manners, even if, in this novel, both protagonists seem intent on flaunting those, and some of the minor characters are not exactly acting within the bounds of propriety either. (Sir Richard attempts to handwave this by saying that he and Pen are a very eccentric couple, which seems to understate the matter.)

But the book is not merely a recycling of previous material (although Heyer was evidently drawing from the research she had done for Regency Buck, An Infamous Army, and The Spanish Bride). Heyer also developed character types that, with minor personality adjustments, would become staples of her later Regency novels: the sighing older aristocratic woman, who uses her frail health and ongoing beauty to control family and friends; the forthright younger or middle aged woman, typically a sister, but occasionally an aunt, bent on practicality, not romance; the silly younger hero desperate to ape the fashionable hero; and the kindly, also practical middle aged woman who helps bring the protagonists together.

All exist in a fabulous world. I mentioned, when I began this series, that the Regency world Georgette Heyer created is in many ways a secondary fantasy world, and this work showcases most of what I meant. This is not the laboriously accurate recreation of the historical Regency world that she had recreated for Regency Buck and An Infamous Army, although her fantastical world is based on both. To take just one minor example, here, it is completely possible for a girl younger than Lady Barbara to flout society’s rules, more so than even the flamboyant Lady Barbara, who at least was not engaging in cross dressing, a not exactly approved of Regency activity, even if practiced by Lady Caroline Lamb, and rather than find herself disgraced and cut off from her relationship (Lady Barbara) or blackballed from society and pronounced insane by kindly relatives (Lady Caroline). Heyer would soften features of Lady Caroline’s story in later works.

But more so than the implausibility of the plot, Heyer also creates here a formal world of specific phrases, mannerisms, and dress, with a significant emphasis on the dressing part. Everyone and everybody in Heyer’s world almost immediately makes character judgements based on clothes and the quality of the tailoring; a subplot of this book involves a catskin waistcoat that is distinctly unstylish, troubling to the eyes, and a characteristic identifier.

Certain elements—those infamous “will she or will she not get those vouchers for the Almack balls”—are not in this book quite yet. And oddly, for a book so filled with froth and improbable coincidences and people openly defying social structures, this is also a book that recognizes the problems with and limitations of these social structures. In later Heyer books, most heroines would find happiness only by conforming to social expectations. Richard and Pen find happiness through defying them, in what was perhaps an unstated cry of defiance against the roles and strictures that World War II was even then demanding from all.

It’s safe to say that Heyer did not immediately realize what she had created, other than a filler book that had given her comfort and distance at a time when she greatly needed it. Her next book was to be that long awaited detective novel which she found so difficult to write, Envious Casca.

Mari Ness, perhaps fortunately, does not own a single catskin waistcoat. She lives in central Florida.

It is a truth universally acknowledged that all sorts of things sound reasonable after enough liquor.

Nevertheless this highly implausible story has the best crack in the whole Heyer ouvre. Someone says, “I’ll be damned.” And Wyndham replies, “The prospect leaves me unmoved.”

The people on the plane wondered what I was laughing so hard at.

This is one of my favorites, more so on each re-read. It’s so full of laughter.

First — you are so right about that cover. A total miss. (Pun entirely unintended.)

Second — I do like the phrase “as one does”.

Third — never knew the exact writing order of Heyer’s Regencies well enough to place her invention of the genre, but it does make sense … and I remember THE CORINTHIAN perhaps only faintly, but with affection. Time for a reread.

—

Rich Horton

The corinthian is one of my all time favourites among the GH books and I laugh even when I’m reading it for the umpteenth time. Who wouldn’t like to get away the way Pen does from a world of prose and proprieties? I do love the way Richard reacts to her actions. They’re such a sporting couple and deserve to be happy!

Thanks for this series of articles. I have often thought it would be interesting to read some Heyer, as she is such an influential author, and you are giving me a far better idea of where to start.

Most of the historical fiction I have read involves action on the rolling decks of ships, and I think it is past time for me to step ashore and try something different. ;-)

@Pam Adams – Truth! (It’s entirely possible that my posts for Tor.com were partly inspired by a touch of hard liquor, though I refuse to confirm that.)

@pilgrimsoul — The insults throughout this book are really great, and often improve on rereading.

@terjemer — Agreed.

@Rich Horton — Heh on “miss.”

Reading the books in publication order is giving me a better sense of their development. You can start to see just how much Heyer relied on the comedic dialogue skills she created for her mysteries in her later Regencies — just as she started having trouble/gave up writing the mysteries.

@swapna dutta — I’m often unconvinced by Heyer’s couples, and, certainly, Pen and Richard haven’t exactly known each other for very long when they fall in love. But this is one Heyer couple that I do think is destined for a happy ending, since in just a few days they’ve learned to communicate with each other, respect each other’s emotions, and, most importantly, get each other. And they have a lot in common — most notably the desire for adventure and for something different. So I think they’ll be happy. And Pen can always dress as a boy later to turn him on….

@AlanBrown — This book is probably one of the better places to start purely for the amusement value, although you are warned that “improbable” is too kind a word for the plot. If you can swallow that — and since it’s presented as complete farce, I think most readers can — it’s a great introduction to Heyer.

[To get it out of the way, I will express my bemusement that, having used “flaunt” for “flout” twice, you use the correct word the third time. This has not completely flummoxed me, but I hope you will consider the matter yourself.]

I don’t remember which Heyer I read first, but I remember my father’s collection of most or all of Heyer’s work. Heyer novels are one of my comfort re-reads, full of delight. Jane Aiken Hodge’s biography was illuminating and memorable; I have recommended it nearly as often as her own work. Hodge discusses Heyer’s extensive collection of original material and research, and her irritation with an imitator’s use of a phrase she’d discovered in a source (a journal?) she owned, but, perhaps because of Great Britain’s libel laws, Aiken does not name the thieving writer. Has anyone here a clue who it was?

@Ann Burlingham — Heyer’s most recent biographer, Jennifer Kloester, mentions two: Barbara Cartland and Kathleen Lindsay. I would have added Clare Darcy but if a quick look on Amazon.com is correct most of Darcy’s books came out after Heyer’s death, so although she’s certainly the most straight out imitator of Heyer I can think of, Heyer probably never found out about her.

Cartland was the major one, since Cartland used a phrase that Heyer had found in a privately owned diary, and Cartland used names similar to those in Friday’s Child and a plot similar to These Old Shades. Heyer was also furious to see Cartland using phrases similar to hers when discussing Regency clothing and then getting the wrong boots for the wrong type of pants (this is the sort of thing that only Heyer would worry about). After Heyer contacted her solicitor the Cartland books in question went out of print.

Heyer herself felt that Lindsay wasn’t “actionable,” and that author was furious about the plagiarism accusations. From Kloester’s account it seems that the Cartland case is pretty straightforward plagiarism; the Lindsay case, found by a Heyer fan, more questionable.

I find most other Regency romance writers* fairly dismal (Cartland perhaps dismalest of all), but I did enjoy (if not overwhelmingly) a couple of Clare Darcy books.

*(I hasten to add that there are a couple of exceptions — a particular favorite is SF writer eluki bes shahar (aka Rosemary Edghill). Another sometime SF writer, Jo Beverly, can be pretty good too.)

Just found The Corinthian in a used book store. I figure that any author who almost singlehandedly starts a new genre deserves a try!

I finally got my hands on this one – it was a charming bit of fluff, but kept reminding me very strongly of Sprig Muslin, which I like much more. I do like that they accept being eccentric so nicely, though.

Am I the only person who sees some reference, however oblique, to homosexuality in this story? Heyer never says anything without a purpose, and there are several references to the fact that Richard is not interested in women – and then he falls for a cross-dressed tomboy. And to quote Mari’s comment: “And Pen can always dress as a boy later to turn him on.”

Brilliant piece, thanks for enlightening us (and thanks to a fellow poster on the GH Appreciation page on Facebook for pointing me to it). I really must read some GH biographies.

@pilgrimsoul – I love “Lady Cinderford will act as hostess at Stanyon over my dead body!” answered by “That would be something quite out of the ordinary way,” in A Quiet Gentleman.

“who at least was not engaging in cross dressing, a not exactly approved of Regency activity”: Babs did! She dressed in Harry’s clothes and walked through Brussels with George (or was it the other way around?)

I remember the first time I read The Corinthian, thinking, “oh, language has changed hasn’t it?” then, “hehe, another unintentional double-entendre,” and then a bit later, “I am beginning to doubt how unintentional these phrases are”. When I finally read one of Heyer’s contemporaries I realised it was ALL DELIBERATE, and while I was hugely amused I could not with a straight face read The Corinthian out loud to my mother.