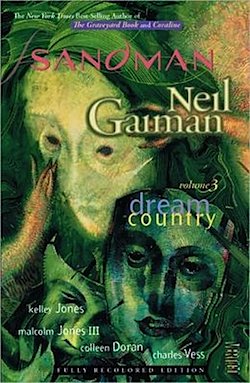

The third Sandman collection, Dream Country, is the shortest of them all, pulling together only four issues of the series, all of which tell self-contained stories set in Neil Gaiman’s darkly fantastical universe.

The Dream Country stories expand the domain of Sandman even further, bouncing from genre storytelling about genre storytelling to the secret history of felines to the supernatural mystery behind one of Shakespeare’s beloved plays to the sad life and beneficent death of a forgotten superhero.

The first chapter, “Calliope,” from Sandman #17, tells the tale of frustrated writer Richard Madoc, who ominously begins the conversation on page 1 with the words, “I don’t have any idea.” He’s referring to the disgusting, mysterious ball of hair held out for him by a collector, but Gaiman’s use of “I don’t have any idea” as the opening line provides a statement about the character and the story. It’s a story about ideas—the age-old question: where do your ideas come from? Here, they come, as they did for the ancient poets, from the muses, specifically the one known as Calliope.

That disgusting hairball was a trichinobezoar, cut from the guts of a young woman who had been sucking on her hair—swallowing pieces—for years. Madoc trades it to old writer Erasmus Fry, a once-successful novelist and poet and playwright who hasn’t been able to write anything for a year. In return, Madoc gets the naked and vulnerable prisoner Fry has been keeping locked in a closet. Calliope herself, whom the octogenarian Fry caught on “Mount Helicon…1927. Greece.” He was 27 years old at the time.

“Calliope” becomes a story about a victim and a captor, with Morpheus (called “Oneiros” here, the Greek personification of dream) as the grim savior. But it’s also a story about rape with Calliope as the literal target of Madoc’s abuse, the writer violating the well of creativity through force. This is a story about the horrors of writer’s block, and the extremes someone will go to so they can produce content for glory. It’s an unromantic look at the creative process, the price that’s paid for success.

Gaiman uses the story to, of course, reflect on the act of storytelling—as he does throughout Sandman—but it’s no celebration of the commercial aspects of the trade. These are desperate writers in this story—Madoc mostly, though we get the clear sense that Erasmus Fry was then what Madoc is now—and there’s nothing wonderful about their work. It comes from somewhere else, not the intangible ether, but from the sordid and terrible abuse of another soul. And Morpheus, sympathetic to suffering and imprisonment, not only frees Calliope (who he shares a past relationship with, and not a pleasant one according to their conversation), but punishes Madoc in vengeful, ironic fashion: he gives the writer an overflow of ideas, more than he can handle. Madoc goes insane, story concepts flowing out of him in a mad fervor…then he ends up with “no idea at all.”

The real horror behind this story seems evident: for a writer, someone who lives off storytelling, it’s not the lack of ideas that’s most frightening. It’s the extremes to which the writer will go, the inhumanity he will sink to, so that the ideas may continue to flow.

Of the four Dream Country issues, “Calliope” is the most traditionally disturbing, and the artwork by Kelley Jones, with lanky forms wrapped in shadow, complements it well.

Sandman #18 is quite a reach for Gaiman and the series, giving us “A Dream of a Thousand Cats,” in which we see a distinctively different take on Morpheus and a story that pushes against the land of trite fantasy and leaps completely out of the realm of horror.

It’s a story of the secret life of cats—a topic that has a history of sucking in even austere creative types like T. S. Eliot—and Gaiman presents it as a dark suburban fantasy in which we see a cat questing for answers, looking to discover why the world is the way it is. The cats are anthropomorphized only in their words and thoughts—they’re drawn (by Kelley Jones, for his second issue in a row) as real-life felines, in what seems to be the “real” world. But as the cat-agonist learns, the world was once ruled by great cats, until the men and women came into the world and dreamed of a better place, where humans would be the dominant species.

“Dreams shape the world,” said the human leader, naked in his pleasure garden, surrounded by his people.

Gaiman tells the story like a fable. A straight-ahead, fantastical, talking-animal fable, of the sort that might be told to children or around the ancient campfire.

That’s the stretch in this story, I think. Not that it features cats as main characters—though there is a bit of over-cuteness at risk with that—but that Gaiman takes what had been largely a horror series, or at least a distinctly dark fantasy series, and turns it, for an issue, into something that risks its own credibility by telling a sweet fable about the inner lives of kittens.

Yet, Gaiman gives it an edge that undercuts its saccharine concept. The cats, here, are the oppressed species, often poorly treated by human masters who see them as playthings. In the final panels, as we see cereal being poured and coffee steaming in a heart-patterned mug, the human husband asks, looking at the sleeping kitten, “I wonder what cats have to dream about?” And we know, because we’ve seen it from Gaiman and Jones. They dream about “A world in which all cats are queens and kings of creation.” They dream of a new world.

The focus on cats, on animal protagonists and secret kitty conspiracies, and the fabulist approach likely softened up Sandman readers for what was coming next: Shakespeare with a twist. A retelling of A Midsummer Night’s Dream, with the “real” faeries that made the story possible.

Issue #19, titled after William Shakespeare’s early pastoral comedy, ended up winning the World Fantasy Award in the “Short Fiction” category, a feat that has never been duplicated by any other comic since. (Mostly because the World Fantasy Awards now only recognizes comic books in the “Special Professional Award” category, likely because prose fantasy writers became annoyed that a mere comic could win such a prize.)

Illustrated by future-Gaiman-on-Stardust-collaborator Charles Vess, Sandman #19’s “A Midsummer Night’s Dream” takes us to a bright summer day in 1593 when “Will Shekespear” and his traveling troupe perform a play commissioned by Morpheus on the rolling hills near the village of Wilmington. Gaiman gives us a great exchange between the two characters on the second page of the story when Shakespeare comments that this outdoor, unpopulated location is “an odd choice of a place for us to perform.”

Morpheus replies, “Odd? Wendel’s Mound was a theater before your race came to this island.”

“Before the Normans?”

“Before the human,” Morpheus responds, with a tight smile and a glint in his eye.

For as Shakespeare soon learns, his play of faeries and love sick humans and misunderstandings and slapstick and folly is not to be performed on Wendel’s Mound for any typical audience. Auberon and Titania—the “real” Auberon and Titania, king and queen of the faerie realm—along with more than a few of their precocious race have come to see the show.

For as Shakespeare soon learns, his play of faeries and love sick humans and misunderstandings and slapstick and folly is not to be performed on Wendel’s Mound for any typical audience. Auberon and Titania—the “real” Auberon and Titania, king and queen of the faerie realm—along with more than a few of their precocious race have come to see the show.

What follows is an elliptical performance of Shakespeare’s play, with Will and his actors looking out at the strange audience that has sat down to watch. Gaiman cuts between scenes of the play being performed and the faeries in the audience, responding to their human alter egos with bemusement. Morpheus, meanwhile, speaks candidly to Auberon and Titania, revealing the genesis of the play—it was one of two he commissioned from Shakespeare in exchange for giving the mortal what he thought he most desired—and espousing on the nature of storytelling itself.

It wouldn’t be a Sandman story, or a Gaiman-written script, if it didn’t comment on the power of stories, would it?

As Morpheus explains, he wanted to repay the faerie lords for the amusement they once provided, and he says, speaking to his invited guests, “They shall not forget you. That was most important to me: that King Auberon and Queen Titania will be remembered by mortals, until this age is gone.”

That’s the stories outlive their creators bit, but then Morpheus goes on to explain the very nature of story to a dismissive Auberon who refers to the play as a “diversion, although pleasant” and objects that in its details it is untrue. “Things never happened thus,” Auberon says.

The shaper of dreams sets the Faerie King straight: “Things need not to have happened to be true. Tales and dreams are the shadow-truths that will endure when mere facts are dust and ashes, and forgot.”

Stories outlive their creators and are truer than the facts upon which they were once based. That is the meaning of Sandman, always and forever, and its clearly articulated here for everyone who has missed the not-so-subtle hints all along, more eloquently than my facile one-sentence-summary.

Yet, that’s not the only moral of the story here. There’s something else: the tellers of the great stories suffer. Morpheus shows this side of the message as well, a bit earlier in the issue, talking to Titania about Shakespeare: “Will is a willing vehicle for the great stories. Through him they will live for an age of man; and his words will echo down through time. It is what he wanted. But he did not understand the price. Mortals never do.”

And here’s the kicker, via Gaiman-through-Morpheus: “…the price of getting what you want, is getting what once you wanted.”

That bit of profound wisdom, from an early-in-his career Neil Gaiman, is easy to read as a warning to himself, to remind himself that it’s the striving that counts, not the success. That kind of psychological reading into the text is too simplistic, of course, because Morpheus is not Gaiman. But if we step outside of the text itself for a minute and think about how Gaiman has handled his success and fame since the early days of Sandman, we see signs of a creator incredibly self-aware of the kinds of stories he’s telling and the kind of writer he has always wanted to be. Even in his younger days, Gaiman seemed able to look back on his then-current work from a safe distance. Maybe the avatar of Dream, eons old, allowed him that perspective. Or maybe that’s what attracted him to Dream to begin with.

If that seems like a logical place to end this post, and an appropriate sentiment upon which Gaiman could have ended the Dream Country cycle, then you’d be right. Because the story in Sandman #20, “Façade,” looks, at first glance, like it doesn’t quite belong immediately after “A Midsummer Night’s Dream.” It’s the sad elegy of a long-forgotten superhero and Morpheus never appears in the issue.

But it does fit. It’s an appropriate epilogue to Dream Country and an appropriate follow up to the award-winning issue that preceded it. It ends, as all things do, with Death. And though Morpheus never pops into the story, his words about “getting what once you wanted” find embodiment in the protagonist presented here: Urania Blackwell, the Element Girl.

Drawn by Colleen Doran, with her normally clean lines appropriately scuffed up by the scratchy inks of Malcolm Jones III, this sad tale of the Element Girl shows what happens long after you’re stuck living with what you wanted. There’s no Dream in this story because there’s no hope for Ms. Blackwell. All she’s left with is her decaying, yet undying, superhuman form.

If I may nod toward pretentious literary allusion for a moment—and this is Sandman we’re talking about, so I should probably feel free to dive in that direction on a regular basis—the tagline for the original house ads for the series was “I will show you fear in a handful of dust,” from T. S. Eliot’s The Waste Land. Eliot begins that famous poem with an epigraph from Petronius’s Satyricon, which translates as “I saw with my own eyes the Sibyl at Cumae hanging in a cage, and when the boys said to her: ‘Sibyl, what do you want?’ she answered: ‘I want to die.’”

It’s a reference to immortality, granted to the Sibyl by Apollo, but as she withers, unable to die, all she longs for is death.

That’s precisely the situation Element Girl finds herself in. She faces another two thousand years of life, in her current grotesque form. Two thousand more years—at least—of loneliness and misery.

Because she got what she once wanted.

Element Girl, in the DC Universe, first appeared in the Silver Age, in Metamorpho #10, written by Bob Haney, creator of the original Teen Titans. Like Metamorpho, Element Girl could change her shape and, as her name suggests, transform parts of her into various elemental states. She was a female doppelganger of Metamorpho, and she was the most minor of minor characters in the DCU, almost completely forgotten until Gaiman resurrected her for this one issue of Sandman.

In this story, she’s a recluse, unable to connect with anyone in the human world because her skin keeps falling off. She’s dried up, desiccated, and though she still has some of her powers, she seems unable to control them. And she has slowly gone insane. As she says to herself, “I think I’m cracking up. I think I cracked up a long time ago.”

But her madness doesn’t manifest itself in harmful ways, not to others, at least. She is just constantly terrified, as she tells Death, when the sister of Morpheus comes knocking: “It’s not that I’m too scared to kill myself. I—I’m scared of lots of things. I’m scared of noises in the night-time, scared of telephones and closed doors, scared of people…scared of everything. Not of death. I want to die. It’s just that I don’t know how.”

Death, in her Manic Pixie Dream Girl mode, doesn’t immediately give Element Girl any help, other than brief companionship. When Urania asks, rhetorically, “I’ve got another two thousand years of being a freak? Two thousand years of hell?” Death simply adds, “You make your own hell, Rainie.”

But Element Girl is too far gone to understand what Death is trying to tell her, and, in the end, she turns to the being who granted her powers back in the old days, when she was, for a moment, someone amazing. She turns to Ra, to the sun. And as she stares up at the face of Ra, at the shining yellow disk rising up over the city, she turns to glass, and then crumbles to dust.

Death never took her away, but she ended up…somewhere. What she once wanted.

Gaiman would later return to the character in the much more whimsical adventures of Metamorpho and Element Girl in the pages of 2009’s Wednesday Comics. But that 12-part serial was more of a romp in tribute to a more innocent era than a thematic echo of what he did here.

Here, he ended Dream Country with a goodbye to the Silver Age of comics, and with the departure of someone who once wished to be something magical.

Her story, though, lives on.

NEXT TIME: Sandman goes to Hell, again, in Season of Mists.

Tim Callahan gave this collection to a professor of his, but it’s likely that the man never made it past the story about all those darned cats.