More than one review of Hild has characterised me as an sf/f writer who has left the fold to try my hand at this historical fiction thing. I’m not convinced I’ve left anything. If I have, I haven’t stepped very far.

When I first started reading I found no essential difference between Greek mythology and the Iliad, Beowulf and the Icelandic sagas. The Lord of the Rings, The Weirdstone of Brisingamen and The Eagle of the Ninth all spoke to me with the same voice: the long ago, wreathed in mist and magic. My first attempt at fiction (I was eight or nine) was a tale of a hero with no name—though naturally his sword has a name, and his horse, and dog. I’ve no idea if there would have been any fantastic element or not because I abandoned it after the first page. A brooding atmosphere, it turned out, wasn’t enough to sustain a story.

My second try (at 10 or 11) was a timeslip novel about a girl who goes into a Ye Olde Curiositye Shoppe—down an alley, of course— finds a planchette (I’d no idea what it was but I liked the word) and somehow goes back to a somethingth-century abbey. I dropped this attempt around page ten—I couldn’t figure out what my hero would do once I’d described both milieux—and didn’t try again until my twenties.

By then science had claimed me. I no longer believed in gods or monsters or spells. But I still believed in the frisson that wonder creates, the sheer awe at the universe, whether outer space, the tracery of a leaf, or the power of the human will.

My first novel, Ammonite, was as much a planetary romance as a biological What-If story. I got to create a whole world, to play with biology and ethnogenesis, language and culture shift. Slow River was another exercise in world-building, this time taking what I knew of communication technology and how people use it, bioremediation and human greed, and extrapolating into the very near future. My next three novels were here-and-now novels about a woman called Aud, often labelled noir fiction—but Aud has a very sfnal sensibility regarding the way the world works. My shorter fiction output is erratic—but it could all fit comfortably into sf/f.

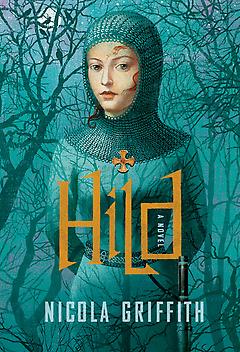

And now there’s Hild, a novel set in seventh-century Britain about the girl who becomes the woman who know today as St. Hilda of Whitby. It’s published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux, and they label it literary fiction/historical.

Every publisher’s marketing department hangs their own label on the work—I don’t blame them, labels are what makes books easier to sell—but I don’t think in those terms. To me my novels are all simply stories.

Then, too, history itself is story, a constructed narrative formed from written and material evidence interpreted through our cultural lens. What we call history probably bears little relation to what actually happened. There again, “what actually happened” varies from person to person. (Canvas those you know about major events such as 9/11, the effects of World War II, HIV; everyone will have a different perspective. And those things happened in living memory.)

So history is a story. And story is a kind of magic. So is it possible for historical fiction to be anything other than fantasy?

When I set out to write Hild I had so many competing needs that thought the whole project might be impossible. Ranged against my need for bone-hard realism was my hope for the seventh-century landscape to be alive with a kind of wild magic—an sfnal sense of wonder without gods or monsters. I was set on writing a novel of character but on an epic canvas. And Hild herself had to be simultaneously singular yet bound by the constraints of her time.

We know that Hild had to have been extraordinary. We just don’t know in what way. The only reason we even know she existed is because of a mention in the Venerable Bede’s Ecclesiastical History of the English People. Bede was writing fifty years after her death; I doubt he ever met her. And he was writing with an agenda: the glory of the new Christian church. Anything that didn’t fit, he left out.

Bede tells us Hild’s mother dreamt of her in the womb—she would be the light of the world. Her father was murdered in exile. She was baptised at age 13 and recruited to the church at age 33—when she was visiting her older sister. She went on to found Whitby Abbey and in 664 CE she hosted and facilitated a meeting, the Synod of Whitby, that altered the course of English history. She trained five bishops, was a counsellor to kings, and was instrumental in the creation of the first piece of English literature, Cædmon’s Hymn.

We don’t know what she looked like, whether she married or had children, or where she was born. We do know that she must have been extraordinary. Think about the fact that this was the time that used to be called the Dark Ages, a heroic, occasionally brutal and certainly illiterate culture. Hild begins life as the second daughter of a widow, homeless and hunted politically, yet ends as a powerful advisor to more than one king, the head of a famous centre of learning, and midwife of English literature.

So how did she do that?

We don’t know. In order to find out, I built the seventh century from scratch and grew Hild inside.

From the very beginning I decided that to get an idea of how it might really have been, every detail of the world had to be accurate. Everything that happened the book must have been possible. So for more than ten years I read everything about the sixth and seventh centuries I could lay my hands on: archaeology, poetry, agriculture, textile production, jewellery, flora and fauna, place names, even the weather. Without everything I learnt over two decades of writing sf/f I couldn’t have built this world.

As seventh-century Britain began to take shape in my head, I started to think about Hild herself. She was the point, the nexus around which everything else would revolve. She would have to be in every scene. But given the gender constraints of the time she couldn’t just pick up a sword and whack off enemies’ heads—she’d have been killed out of hand and flung facedown in a ditch. She would have to use other tools to lead in a violent culture. What she had was a subtle and ambitious mother, height, status, a will of adamant, and a glittering mind. Sometimes that can look like magic.

If you asked Hild herself if she was just a little big magical, I’m not sure she would understand what you were saying. She believes in herself. She believes in something she calls the pattern. Some of us might call it god; others would call it science. She is a peerless observer and loves to figure out patterns of behaviour in people and the natural world. She doesn’t have a philosophy of science, of course, nor does she understand the scientific method, but I suspect that today she might seek understanding through science.

The other day in the pub a friend asked flat-out: is Hild fantasy or not? I couldn’t answer. All I know is that story itself is magic. Story should brim with wonder. It should own you and make you see the world differently, just for a little while.

Nicola Griffith has won the Nebula Award, the James Tiptree, Jr. Memorial Award, the World Fantasy Award, and six Lambda Literary Awards. She is also the co-editor of the Bending the Landscape series of anthologies. Her newest novel, Hild, publishes on November 12th. She lives in Seattle with her partner, writer Kelley Eskridge.