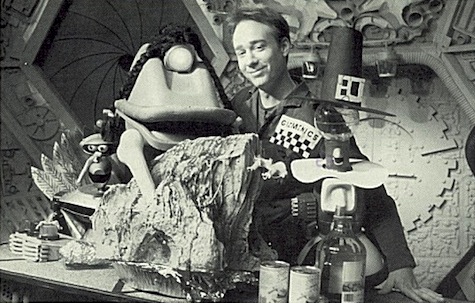

This week marks a milestone for all of humanity—Sunday was the 25th anniversary of the first broadcast of Mystery Science Theater 3000. The first ever episode, “The Green Slime” was shown on a small Minneapolis cable-access channel called KTMA on November 24, 1988. This is also the 22nd anniversary of the Turkey Day Marathon, which aired annually on Comedy Central from 1991 until 1995, and which will be returning this year! Joel Hodgson is curating an online marathon that will be available this Thursday starting at noon Eastern Time.

There are many things to say about MST3K, (and eventually I plan to say all of them) but since this is Thanksgiving week I wanted to thank the show’s writers for helping me with a very specific issue I had as a kid.

My parents had me late in life, and their parents were also a bit older when they had them—both sets of grandparents were too busy surviving the Depression to get married right away. Because of this I had a slightly larger cultural gap with my family than most of my friends did, and I was confused by their volatile relationship with their own childhoods. For me, it was easy: I liked nerdy things, I wanted to be a Jedi, and I didn’t care too much whether I fit in with the kids at school or not. My parents really cared about how other people saw them. They worried about not being Catholic enough. They went through phases of strict morality, but then punctured them by showing me Monty Python and telling me jokes about priests.

The thing that helped me understand this was my discovery of MST3K. Specifically, it was the shorts the guys occasionally riffed that helped me understand my parents’ childhoods. The shorts themselves are bite-sized propaganda with titles like “The Home Economics Story,” “Appreciating Our Parents,” “Body Care and Grooming,” and, probably best of all, “A Date With your Family.” They gave me a unique window into the culture and mindset of the 1950s and 1960s, because they’re pure social engineering, there is no aspiration to art, or even commerce—what they’re selling is a way of (white, middle-class) life which was only imaginable in the years after WWII. Without the veneer of fiction or glossy actors, the naked desires of the 1950s are exposed, and they turn out of mostly be a desire for libidos to be “starched and pressed” and for people to remain as pleasant and surface-level as possible.

In this world, social survival must be bought by rigid conformity to a cultural standard. You do what you’re told, you respect authority in all of its forms, and you absolutely perm or oil your hair, respective of gender, exactly the way your peers perm or oil their hair. The uniformity of these shorts gave me a concentrated dose of 1950s life—there is no irony, no self-reflection, no winking: this is what mainstream America wanted to look like. Or, more importantly, this is the ideal they wanted their children to make reality.

This is what my parents were raised to want to be.

And it’s fucking terrifying.

Naturally, being my parents, and very intelligent, they’ve spent their whole lives arguing with these ideals. And, thanks to the MSTies, I learned how to, too. You saw when I mentioned “no irony, no winking” thing? That extreme seriousness allowed the MST3K writers to create some of their darkest jokes and some of their most memorable riffs. With no characters or plot to worry about, they were free to focus on pure social critique. Many of the shorts turn into a battle between the Bots and the stern male narrators of the films. Crow particularly takes on the voice of the Narrator to subvert his insistence on conformity.

The shorts tend to focus on family life, cleanliness, and morality, but most of them have a solid throughline of guilt and shame. “Appreciating Your Parents” seems OK at first—a little boy realizes that his parents work hard, so he starts cleaning his room and helping with the dishes. So far, so good. But then you think about the fact that at the age of 7 this kid is saving his allowance because he’s worried about the family’s savings, and it becomes a much darker story. How much guilt has this kid internalized? Why are his parents letting him think that his weekly quarter is going to land them in debtor’s prison? Should an elementary school boy be hoarding money in Eisenhower’s America, or has Khrushchev already won?

Then there’s “A Date With Your Family.” This short takes the innocuous idea that families should try to sit and eat meals together, and turns it into a Lynchian nightmare of secrets and repressed sexuality. The Narrator (Leave it to Beaver’s own Hugh Beaumont!) is especially angry. I had already watched this short many times, but this week I noticed something truly frightening: every emotion is qualified with the word “seems.” For instance:

Narrator: They speak with their dad as though they are genuinely glad to see him.

Crow [as Narrator]: They’re not, of course…”

I mean, seriously, would it have been so hard for the kids to just be glad to see their father? Then there’s this:

Narrator: They converse pleasantly while Dad serves.

Mike [as Daughter]: No, I—I’ll just have Saltines.

Narrator: I said “pleasantly,” for that is the keynote at dinnertime. It is not only good manners, but good sense.

Crow [as Narrator]: Emotions are for ethnic people.

Narrator: Pleasant, unemotional conversation helps digestion.

Servo [as Narrator]: I can’t stress “unemotional” enough.

“Dinner Don’ts” are illustrated, for instance when “Daughter” talks animatedly to her family for a few minutes:

Infuriating her father:

Narrator: Don’t monopolize the conversation and go on and on without stopping. Nothing destroys the charm of a meal more quickly.

Mike [as Narrator]: …than having a personality.

Meanwhile, the shorts that I group as Grooming = Morality are fanatical, and promote a basic Calvinist worldview that the better your exterior looks, the better your interior must be. The connection between being “neat” and “looking exactly like everyone else” is blatant in these films, but the shorts are so committed to shaming their actors for individuality that when they play up the religious aspects in one like “Body Care and Grooming” it feels like they’re just reading between the lines:

Narrator: Clothes are important. Besides fitting well and looking well, the clothes should be appropriate for the occasion. Wearing inappropriate clothes, like these shoes—

Servo [as the Narrator]: Is immoral.

Narrator: —is a sure way to make yourself uncomfortable… and conspicuous.

Crow: Expressing individualism is just plain wrong.

Then you hit the straight up Morality ones like “Cheating.” In “Cheating”—Johnny lives in a perpetually dark home, where he sits beside a ticking Bergmanesque clock, and the faces of those he’s wronged floating before him.

I’m not kidding:

That’s cause he cheated on a math test. Really. That’s it. He didn’t murder his landlady, or participate in a genocide. He got a 92 on a math test instead of like an 80 or something. He gets kicked off the student council, and the kid who tells him the news seems actively happy.

This is the unforgiving world my parents grew up in, and that’s before you get to all the Pre-Vatican II Catholicism.

It’s obvious to say that by exaggerating the seriousness of the films, the MSTies point out their absurdity, but for me it was more that by making the shorts the subject of their strongest critique they show the hypocrisy of this worldview. This is their best example of talking back to the screen, to Dad, to Authority in general, and by highlighting the distance between my essential worldview (do what thou will under snark… and love, I guess) and the one my parents had been raised with, I was able to create a better language for talking with them.

Now, do you want to talk about women? We can’t even talk about race, because there are only white people in this universe—they’ve imagined a Wonder Bread-white world that completely ignores any of the actual social upheaval of their time. But we can talk about the fact that the gender relations in these things… well, they leave a bit to be desired. There’s the ordinary sexism on “A Date With Your Family”:

Narrator: The women of this family seem to feel that they owe it to the men of the family to look relaxed, rested, and attractive at dinnertime.

But at least everyone shares equally in the horror in that film. In “Body Care and Grooming,” we’re introduced to a boy who is studying in public.

The Narrator wants to distract him with romance for some reason, and hopes that a pretty girl will walk by. When she does, she’s making the classic blunder of thinking in public, reading and taking notes while she walks. She is shamed by the narrator for having uneven socks.

Narrator: Sorry, Miss! We’re trying to a film about proper appearance, and, well, you’re not exactly the kind to make this guy behave like a human being!

Joel: [bitterly] You know, make him want to grope you and paw at you!

Once she is shamed into combing her hair and not carrying those dirty books around everywhere, she’s presented as an ideal:

“The Home Economics Story” is the worst offender, though. It was produced by Iowa State College to encourage girls to go on to higher education, which in 1951 was still pretty revolutionary. But it’s all undercut by the fact that any pure learning that is offered to the girls, like physics class, has to be justified with the disclaimer that girls will need the information to be better homemakers. The longest sequences in the short focus on childcare.

The tone is pretty well summed up at the end:

Narrator: Jean and Louise were leaving for their jobs in the city, so you all drove down to the train station to see them all.

Servo: And to re-enact the last scene from Anna Karenina.

My mom didn’t go for Home Ec, she did the secretarial track, and ended up being a very highly regarded key punch operator in Pittsburgh. But it’s good to know that her society condemned her for wanting to be financially stable.

One of the weird things with MST3K is that unlike a lot of humor, it’s all about empathy (especially in the Joel years) and one of their tropes was staying on the side of the downtrodden characters. This emphasis on empathy in turn informed my dealings with my parents, even when they were at their most Eisenhowerian. So thank you MST3K, for helping me understand my family a little better! It may sound silly, but watching these shorts made me waaay more patient when my parents worried about my dating habits and utter lack of interest in conformity, girl clothes, marriage, etc. And I think that, with a little bit of guidance from me, my parents have mostly recovered from being exposed to these films at an impressionable age.

And what about you, viewers at home? Are there any pieces of pop culture you wish to thank?

Leah Schnelbach has a lot more pieces of pop culture to thank, actually. But MST3K always wins. She’s also thankful for Twitter!

I immediately think of those clips as being training films for an alien invasion. The narrator (HiveMaster 17) uses seems to illustrate a successful replacement via pod technology.

Wonderful job, Ms. Schnelbach, at uncovering the hidden value of those amazing and amazingly snarky MST3K shorts. Having come of age at the tail-end of the Age of Uniformity, I spent the 1960s peeking over the fence at all the explosions of individuality and wishing I could join in. So, the MST3K shorts and commentary (“Conform! Conform! Conform!” from “Mr. B. Natural”, the most surreal of the shorts, IMO) helped me understand just why I felt so whiplashed by my childhood. And maybe why I hated The Wonder Years, but that is a whole other kettle o’ fish.

I would also like to thank all those wild and cheesy ad pages in the comic books of my youth, too. They were a window on yet another world that existed outside but alongside my more “well ordered” life, promising me superpowers like X-ray vision (via easily affordable spectacles) and physical and/or mental disciplines that would bring respect (transforming me from 98-lb. weakling into The Hero of the Beach) or immortality and social domination (“What POWER did THIS MAN POSSESS?” shouted the Rosicrucians at me). Everything I learned worth learning was to be found on those pages.

I saw my first ep of MST3K back in march of 1991 in a bar across the naval base I was asigned to at the time. I would go there about every saturday and watch with others. Loved the show.

You should, however, note that those are instructional films, and that implies that they illustrate establishment’s wishes which were not congruent with reality. Any default behavior needs not explicit instruction. Instructions are always an error signal feedback in behavior control loop. If an error is persistent, e.g. if there is a permanent repeating of certain instruction, it shows poor responsiveness, stemming from bad design of the system – unrealistic goals.

Ergo, you can’t use these as perfect description of how people actually were back then – only as a mind map of their leadership.

Maybe it would be better to learn about your parents by talking to them? I’d like to throw in something my mom and dad told me this weekend that surprised me. They had extremely different backgrounds, but neither of them took baths regularly until after WW2. They knew nothing about hygiene- dad learned to take regular showers in the Navy, something that then started to trickle down (according to him) into the general public when soldiers returned from the war.

Instructional videos about cleanliness and grooming were trying to correct a problem that it seems a whole lot of America had. You can read some things into what they’re saying is ideal, but they were likely just trying to make that notion attractive to people who didn’t understand why they should bother with something they didn’t need to do until that point.

While there are some things mentioned here that are rather distressing (emphasis on appearance, gender disparity, etc.), a couple points you mentioned hardly seem objectionable to me. Be warned: what follows is a rambling, honestly quite annoying bit of word vomit.

First off, I find it silly that a seven-year-old child concerned with financial stability should engender such horror. “He’s saving his allowance? He realizes the world is unpredictable, and that a measure of caution may be prudent? Oh, the inhumanity!” I mean, growing up, neither my siblings nor I received an allowance at all! We were raised to respect the value of money. If we wanted “pocket cash”, we could volunteer for more difficult tasks than the usual chores. We’ve survived lay-offs and moves across country, but we’ve all managed to keep our heads and remain solvent. Reality has taught us all frugality.

Second, why should cheating academically (or in virtually any matter) be treated with anything other than disdain? While exhulting over another’s humiliation is disgusting, making light of dishonesty is hardly a better alternative. Dishonesty is at the heart of countless problems. You’re mad at financial institutions? They cheat to gain supremacy. Angered by corruption? More cheating. No, cheating on a math test is not going to destroy Main Street, but it can make you an intolerable person. We can all weep for the distraught student-cheater, but let the car salesman rip you off and there’ll be hell to pay!

I don’t want kids to grow up all “repressed” and confused, but at some point reality has to be faced. The world is not a (what is the phrase John Green used?) “wish-granting factory”. You can play by the rules, be honest and hard-working, and still lose; integrity doesn’t mean easy living. What it does mean is a bit of peace at night, knowing that you’re not intentionally being a self-serving egotist.

Me? I got lucky in life –great parents, siblings, growing up amidst cornfields in Indiana (“I knew he was a weirdo!”). We didn’t watch a lot of TV -we lived life outdoors. There were fences to build, sheds to repair, horses to tend, snow to shovel. We weren’t at all perfect, but our parents were forgiving, and they drew lessons from life situations as we experienced them. Not everyone can say that, so I realize that my little rant here is coming from an entitled position. I had it easy growing up, so turning out a jerk would be pretty damning on my part. *looks at angry words above* Waitaminute…

Still, all that (utterly superflous) stuff said, I definitely agree that we should always regard societies intentions with discernment. Whatever side of the argument we fall on, it’s best when we’ve looked at the matter critically. Thank you for your article!

@shellywb : Talking to your parents is so unfashionable. Those rusty old dinosaurs don’t even use Twitter! /sarcasm

I agree with you absolutely, by the way. Personal communication can go a long way in developing as a person. It’s a true exercise in empathy.

With some people it isn’t as easy as “talking = true empathy” because for one reason or another you cannot talk to them. Not every parent is willing – or able – to be open and not every relationship allows it.

Sometimes we have to find alternative ways of connecting to our parents, if we even can connect at all.

I can certainly relate to that situation, so many kudos to Leah for sharing something so personal.

When I was a kid, we had to watch those “instructional” shorts in school. Even at the age of 8, I knew — and most of the other kids did too — that they were “propaganda”, and we despised them, and the adults who pushed them, for their brainwashing attempts. I have to wonder how much these school propaganda films of the ’50s created the youth rebellions of the ’60s.

This is very interesting, I never knew that MST3K riffed on this kind of shorts. These speak to a conformity and rigidity, and supression of actual feelings that is very much the source of a lot of current problems in the world in general, and the US in particular. While 1950s kids in other places of the world were taught to be proper, it was never such an obsession, at least not in Hispanic/Latin cultures like mine. Still, my mother (born in the late 30s and grew up in the 40s and 50s), and other people her age or similar still associate (well, she did when she was alive) “proper appearance” with “moral fiber”; due to their influence, most of society still thinks that you have to wear a shirt and tie and not have a long beard or tattoos or piercings in order to be an upstanding citizen.

I’ve been meaning to watch MST3K (I’ve only seen random bits), and this is a good place to start.

I’ll second the comment about these shorts being prescriptive, not descriptive. I remember a group of us being yelled at for chanting “It’s only a movie… It’s only a movie” during a particularly ridiculous anti-drug film (starring Sonny Bono, if I remember correctly). Also, while analysis valuable, the most important thing in “The Home Economics Story” has to be, “Look! Look! Look at my crotch!”