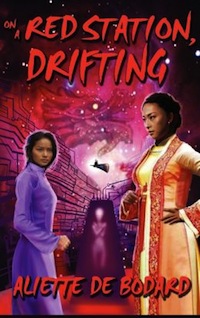

I don’t know if it’s possible to call Aliette de Bodard’s On a Red Station, Drifting (from the UK’s Immersion Press) a quiet work, although under other circumstances I might be tempted to do so.

Riven with tension so well-strung the prose practically vibrates under its influence, its contained setting and ever-tighter circling of consequences essentially subverts the popularly-understood derogatory overtones of domestic conflict.

Linh, a magistrate, arrives at Prosper Station a refugee from a war that’s tearing the outer edges of the Empire apart. Instead of staying with her tribunal—and dying with them, when the invading warlord’s forces took the planet—she fled. Prosper Station is home to distant family, but Linh, educated, self-assured (verging on arrogant), an official used to power, is out of place on a station whose resources have been depleted by refugees, whose greater personages have all been called away by the exigencies of war.

Quyen is the most senior of the family left on Prosper Station. The lesser partner in a marriage alliance who expected to spend her life in domestic concerns, the position of Administrator of Prosper Station has fallen to her. And among her concerns as administrator is to find a place for Linh, to sort out theft and honour among the family, and to preserve the Mind that directs and controls the lived environment of the station: the AI that’s an Honoured Ancestress to the whole family. For the influx of refugees has put a strain on the Mind’s resources, and things do not work quite as they should.

Quyen and Linh don’t get along. Each sees in the other an unwarranted arrogance, a reaching-above their proper station: each resents the other for her attitudes and behaviours. This isn’t helped by a large amount of pride on all sides, by Quyen keeping messages from Linh, and Linh keeping a dangerous secret: her memorandum to the Emperor on the conduct of the war may be taken as treason, and her presence on Prosper Station thus put all her relatives at risk of sentence of death.

This short novel—technically, a novelette, but it feels as though there’s meat enough for a novel here—is divided into three sections, each of which builds thematically on their own and in aggregate towards an emotional crescendo. The middle section has for its centrepiece a banquet welcoming an honoured visitor to the station. The amount of tension, emotional and social, involved in the preparation of a meal—with poetry, calligraphy, everything right and proper—puts many an action-sequence to shame.

You may have noticed I’m a little enthusiastic about On A Red Station, Drifting. If it has a flaw, it’s that I would have dearly enjoyed more time, more background, more of the universe in which it takes place. It’s not the too-frequent predictably American vision of the future, and I for one rejoice in its difference.

Although the conclusion feels a little rushed, it closes its emotional arcs out satisfyingly. On A Red Station, Drifting leaves the reader with a pleasant, thoughtful aftertaste. I recommend it highly.

PS. While de Bodard has set other stories in the same continuity, there is as yet no full-length novel. I have to say, I hope she writes one there—or more than one.

Liz Bourke is a cranky person who reads things. Her blog. Her Twitter.

I agree — there’s lots going on that is not action, and it is definitely not “Americans in Space!”, which is a welcome change. It’s tantalizing, having all those details about the Empire just hinted at. Although it doesn’t seem very long, it covers a lot of events on the station and within the family, and all without info-dumping. Reminds me in some ways of Melissa Scott’s space novels, particularly the way the reader is put right into the middle of the story, and the larger picture is teased out along the way (and probably the AI as well — Scott’s books feature several versions of AI). Still, this is a completely different approach to space, and one that leaves me begging for more.

I adore the stories she’s written in that universe. Red Station kind of blew my mind and changed my preconceived notions of what space opera could be.

Sounds interesting, although I find shortish works a little frustrating as I get kicked out too soon.

The combination of “immersion” and “press” has a different set of strong associations for me, as an Irish person.

http://en.m.wiktionary.org/wiki/hot_press

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=52bna-tn_dY