“What did you ask, Andy Bissette? Do I ‘understand these rights as you’ve explained em to me’? Gorry! What makes some men so numb? No you never mind—still your jawin and listen to me for awhile. I got an idear you’re gonna be listenin to me most of the night, so you might as well get used to it. Coss I understand what you read to me! Do I look like I lost all m’brains since I seen you down to the market? I told you your wife would give you merry hell about buying that day-old bread—penny wise and pound foolish, the old saying is—and I bet I was right, wasn’t I?”

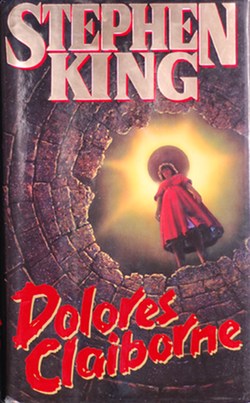

Ladies and gentlemen, welcome to Dolores Claiborne, Stephen King’s 305 page novel. Written in dialect.

King’s first novel to be told entirely in first person, and without chapter breaks (something he hadn’t tried since Cujo) Dolores Claiborne takes place after the titular character, a hard-scrabble, middle-aged housekeeper and mother living on the imaginary Little Tall Island, Maine, turns herself in to the police who want her in connection with the murder of her elderly employer, rich woman and professional harridan, Vera Donovan. It turns out that Dolores didn’t murder Vera, but over the course of the narrative she does confess to murdering her husband back in 1963. The novel is a narration of her confession to the cops and we’re there to hear it all, every last “just us girls” aside to the stenographer, every plea for a sip of whiskey, every smackdown laid on the cops doing the questioning, every sigh, and every reference to boogers. And there are a lot of references to boogers. In fact Dolores Claiborne is probably Stephen King’s most boogery book.

? It’s also written in dialect. I’m from the South and so my relationship with dialect is complicated but my reaction to it is visceral: I hate it. Dialect, for me, brings up associations with Uncle Remus and books written in African-American dialect that sound like a rusty saw blade being stabbed into my eardrums. As if that’s not bad enough, you also have novels that feature Southern characters whose speech is written in dialect and that feel like the same rusty saw blade being pulled out my eardrums in the opposite direction. Writing dialect feels patronizing to me, something that educated whites use to depict those they regard as their inferiors. It’s a way to insert class and snobbery in a book while pretending not to be doing any such thing, a way to “other” a human being through their speech rather than their appearance.

It’s also written in dialect. I’m from the South and so my relationship with dialect is complicated but my reaction to it is visceral: I hate it. Dialect, for me, brings up associations with Uncle Remus and books written in African-American dialect that sound like a rusty saw blade being stabbed into my eardrums. As if that’s not bad enough, you also have novels that feature Southern characters whose speech is written in dialect and that feel like the same rusty saw blade being pulled out my eardrums in the opposite direction. Writing dialect feels patronizing to me, something that educated whites use to depict those they regard as their inferiors. It’s a way to insert class and snobbery in a book while pretending not to be doing any such thing, a way to “other” a human being through their speech rather than their appearance.

Reading dialect forces me to hack my way through a jungle of patronizing “local color” and condescending smirks to get at the text and by the time I get there I’m usually irritated. I don’t mind a writer who captures regional or ethnic speech patterns by changing word order, using words in a different context, or creating new words, but when a writer starts to drop letters and insert bad grammar into their writing because “that’s how these people talk” what they’re implying is, “Because they don’t know any better.” Every time an author puts an apostrophe in their text to indicate a dropped “g” (“she goin’ home”, “I’m likin’ that moonshine”) I see a nod to the reader, “I, the educated author, of course know how to spell this word correctly but when I’m writing a character of a lower class and education level than myself I want to make sure you know that they are too stupid to speak correctly. Let us now snicker amongst ourselves.”

My issues with dialect aside, King’s style is the biggest problem with Dolores Claiborne. To put it bluntly, Stephen King has a hard time not sounding like Stephen King. No matter how many times he inserts “gorry” and “accourse” into his text in an attempt to vanish into Dolores Claiborne’s voice, the illusion occasionally fails. At one point, Dolores, a woman we’re repeatedly told is under-educated, says “Lookin at her that way made me think of a story my grandmother used to tell me about the three sisters in the stars who knit our lives…one to spin and one to hold and one to cut off each thread whenever the fancy takes her. I think that last one’s name was Atropos.” Really? Atropos? Are you kidding me? That’s a name Stephen King knows, not the character he’s been describing for almost 200 pages.

My issues with dialect aside, King’s style is the biggest problem with Dolores Claiborne. To put it bluntly, Stephen King has a hard time not sounding like Stephen King. No matter how many times he inserts “gorry” and “accourse” into his text in an attempt to vanish into Dolores Claiborne’s voice, the illusion occasionally fails. At one point, Dolores, a woman we’re repeatedly told is under-educated, says “Lookin at her that way made me think of a story my grandmother used to tell me about the three sisters in the stars who knit our lives…one to spin and one to hold and one to cut off each thread whenever the fancy takes her. I think that last one’s name was Atropos.” Really? Atropos? Are you kidding me? That’s a name Stephen King knows, not the character he’s been describing for almost 200 pages.

King is an over-writer, but he’s turned all of his characters into overwriters. When Dolores’s sixteen-year-old daughter leaves a note for her mother on the kitchen table it is of a length not seen since the 18th century. Dolores herself is described as being taciturn and to-the-point and yet the entire book is a monologue that few people, save Stephen King, would have the stamina to deliver. On top of that, Dolores Claiborne feels like a book that’s been written by an author who just came back from Costco where they’re having a sale on semicolons. Those high faluting punctuation marks are sprinkled all over the pages like fairy dust and they jar with the blue collar voice we’re supposed to be reading. All words flow through King and so all words sound like King. It’s not the end of the world, but when he’s straining so hard to capture another voice the times he gets it wrong sound like a trunk full of tin plates being thrown down a flight of stairs.

Dolores Claiborne is linked to King’s previous 1992 novel, Gerald’s Game, by a psychic flash that takes place during the 1963 solar eclipse when Dolores kills her abusive husband at the same time that Gerald’s Game’s Jessie Burlingame is being molested by her father over by Dark Score Lake and the two women are briefly given access to each other’s thoughts. It also shares Gerald’s Game’s tendency to be a bit too on-the-nose. Dolores’s abusive husband has exactly zero redeeming qualities, reducing him from a character to a cartoon. He’s a whiner, a coward, an unemployable drunk who molests his children, picks his nose (at length), and bullies his wife. Dolores’s daughter, Selena, is molested by her father and the molestation feels practically like King pulled its details from a child abuse awareness pamphlet and is going down the checklist: wearing baggy clothes—check, depression—check, no longer interested in friends or other activities—check, light goes out in eyes—check. In addition, just as Jessie from Gerald’s Game must overcome her traumatic memories from the past in order to triumph in the present, Dolores must overcome her memories of her dad “correcting” her mother when she was a child before she can stand up to her own abusive husband, something that reduces complex human behavior to a mathematical formula.

Dolores Claiborne is linked to King’s previous 1992 novel, Gerald’s Game, by a psychic flash that takes place during the 1963 solar eclipse when Dolores kills her abusive husband at the same time that Gerald’s Game’s Jessie Burlingame is being molested by her father over by Dark Score Lake and the two women are briefly given access to each other’s thoughts. It also shares Gerald’s Game’s tendency to be a bit too on-the-nose. Dolores’s abusive husband has exactly zero redeeming qualities, reducing him from a character to a cartoon. He’s a whiner, a coward, an unemployable drunk who molests his children, picks his nose (at length), and bullies his wife. Dolores’s daughter, Selena, is molested by her father and the molestation feels practically like King pulled its details from a child abuse awareness pamphlet and is going down the checklist: wearing baggy clothes—check, depression—check, no longer interested in friends or other activities—check, light goes out in eyes—check. In addition, just as Jessie from Gerald’s Game must overcome her traumatic memories from the past in order to triumph in the present, Dolores must overcome her memories of her dad “correcting” her mother when she was a child before she can stand up to her own abusive husband, something that reduces complex human behavior to a mathematical formula.

But there’s a part of this book that is so deeply felt that it defies criticism. It’s very clearly based on King’s own mother, Nellie Ruth Pillsbury King, who raised King and his brothers after her husband abandoned them. In Danse Macabre King writes, “After my father took off, my mother landed on her feet scrambling. My brother and I didn’t see a great deal of her over the next nine years. She worked at a succession of low-paying jobs…and somehow she kept things together, as women before her have done and as other women are doing even now as we speak.”

Ruth King died while Carrie was still in galleys, so she never got to enjoy her son’s success, but the character of the blue collar working mother whose child goes on to enjoy literary success thanks to her back-breaking labor recurs frequently in King’s fiction, and she is always written with a lot of love, affection, and understanding. One of the first is Martha Rosewall, a black hotel maid, who appears in King’s short story “Dedication” (collected in Nightmares and Dreamscapes) which he wrote back in 1985. In the notes to that story he writes, “…this story, originally published in 1985, was a trial cut for a novel called Dolores Claiborne.” There are also seeds for Little Tall Island in King’s short story “The Reach” published in 1981 and collected in Skeleton Crew.

Ruth King died while Carrie was still in galleys, so she never got to enjoy her son’s success, but the character of the blue collar working mother whose child goes on to enjoy literary success thanks to her back-breaking labor recurs frequently in King’s fiction, and she is always written with a lot of love, affection, and understanding. One of the first is Martha Rosewall, a black hotel maid, who appears in King’s short story “Dedication” (collected in Nightmares and Dreamscapes) which he wrote back in 1985. In the notes to that story he writes, “…this story, originally published in 1985, was a trial cut for a novel called Dolores Claiborne.” There are also seeds for Little Tall Island in King’s short story “The Reach” published in 1981 and collected in Skeleton Crew.

King had originally planned to take the summer of 1991 off and to write Dolores Claiborne that fall, but he had the idea for Gerald’s Game and started working on it in the summer, then decided to link both books into a novel called In the Path of the Eclipse, an idea he later rejected when both books both ran long. Dolores Claiborne was released in November 1992 in a first printing of 1.5 million copies, and it instantly hit #1 on the New York Times Hardcover Bestseller list. When it was released in paperback in 1993 it eventually climbed to #1 on that chart, too, something that Gerald’s Game never managed. Dolores is one of Stephen King’s favorite of his own books, one he says “goes in” like Misery, The Shining, and Pet Sematary, and in an interview he says, “If a novel is not an entertainment, I don’t think it’s a successful book. But if you talk about the novels that work on more than one level, I would say Misery, Dolores Claiborne, and It.”

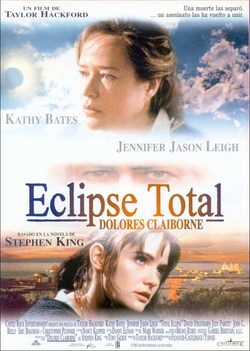

Despite the title, what drives the book isn’t so much Dolores Claiborne herself. Really it’s Vera Donovan, Dolores’s employer, a wealthy woman, and a type-A monster who is a stickler for housekeeping details. Her relationship with Dolores is the engine that powers this book and she’s so popular that two of her lines (“Sometimes being a bitch is the only thing a woman has to hold on to,” and “An accident can be an unhappy woman’s best friend.”) became the tag lines for the movie adaptation, starring Kathy Bates and Jennifer Jason Leigh. Some readers were disappointed that there wasn’t enough horror in Dolores Claiborne but the scenes of Vera Donovan, elderly and no longer in control of her bowels, crapping her bed as part of her campaign to drive Dolores crazy, become moments of pure horror as King delves into the failure of the human body and the grotesque indignities of growing old.

Despite the title, what drives the book isn’t so much Dolores Claiborne herself. Really it’s Vera Donovan, Dolores’s employer, a wealthy woman, and a type-A monster who is a stickler for housekeeping details. Her relationship with Dolores is the engine that powers this book and she’s so popular that two of her lines (“Sometimes being a bitch is the only thing a woman has to hold on to,” and “An accident can be an unhappy woman’s best friend.”) became the tag lines for the movie adaptation, starring Kathy Bates and Jennifer Jason Leigh. Some readers were disappointed that there wasn’t enough horror in Dolores Claiborne but the scenes of Vera Donovan, elderly and no longer in control of her bowels, crapping her bed as part of her campaign to drive Dolores crazy, become moments of pure horror as King delves into the failure of the human body and the grotesque indignities of growing old.

Like Gerald’s Game, the success of Dolores Claiborne is qualified: the dialect is annoying (to me), the voice makes some significant missteps, and some of the book is a bit too on-the-nose. At the same time, Dolores is someone you remember, and her relationship with Vera is a joy to read, whether the two women are trying to drive each other insane, or Vera is tormenting Dolores, or they are actually talking together like equals. But more than any of this, Dolores Claiborne ultimately has to be judged a success because it shows that King, unlike most bestselling authors of his stature, was not interested in capitalizing on his success by setting up a franchise, or by turning out more of the same. He was still committed to the story, wherever it took him. As he said:

“I’m just trying to find things I haven’t done, to stay alive creatively. When you’ve made as much money as I have, there’s a huge tendency to say you won’t rock the boat; you’ll just keep the formula flowing. I don’t want to fall in that trap.”

Grady Hendrix is the author of Satan Loves You, Occupy Space, and he’s the co-author of Dirt Candy: A Cookbook, the first graphic novel cookbook. He’s written for publications ranging from Playboy to World Literature Today and his story, “Mofongo Knows” appears in the anthology, The Mad Scientist’s Guide to World Domination.

While I am sure that some authors do use dialect in the way you indicate (I can’t speak for king in this book, but in Wolves of the Calla he uses dialect to , in my opinion, really give a feel for the calla and it’s people.), your claim is far to strong, that use of dialect is inherently condescending or perpetrating racial and cultural stereotypes. Dialects are do important to real language that linguists often consider them sub languages. So there is Appalachian English, differrent varieties of African American English, etc. these dialects can follow differrent linguistic rules than standard English. So if you want to write a story about people in the Appalachians, then you should have them speak Appalachian English, since that is what those people do. There is no “correct” way to speak. It’s not as if the rules of English were carved on a stone tablet by god. Dialects used correctly are just another tool in the writer’s toolbox.

From your article it’s clear that your references to dialect are mostly concerned with the US and Southern dialects in particular. I’m interested in what you think of Irvine Welsh’s use of Edinburgh dialects in his work? Does it make a difference if you know the author comes fom the same background and culture they’re describing? For what its worth I dislike dialect in novels in general as it gets in the way of comprehension. Where a few choice phrases or idioms would give the flavour and feel of a time and place, too much dialect just drowns the reader in an author’s ideas of how to spell phonetically.

2: yes, I think it’s very likely that someone who associates all dialect writing with Uncle Remus is going to have a different opinion of it than someone who associates it with Irvine Welsh – or indeed Mark Twain or Iain Banks or Salman Rushdie or JM Synge or Ben Okri.

And, you know, undereducated doesn’t mean completely ignorant of everything that we think of as high culture either.

Gee, whenever I read something in dialect I think “this character has some sort of accent particular to a region, and it is probably being used for a reason”

I also think the author is attempting to imitate a speech pattern, and vernacular expressions that they may or may not know very well themselves, if they do not do the imitations very well I assume it is the author that is undereducated.

Actually, this whole anti-dialect tirade is the most annoying thing ever.

Wow. You must hate Mark Twain’s work with the burning passion of a thousand white hot suns.

Yeah. The anti-dialect rant smacks of projection. I’ve lived in the South more than 20 years and I’ve met plenty of highly intelligent people that don’t speak properly. Dialect and intelligence are not interdependent, and that you assume that King is making such an allegation seems more a reflection of your own views than the author’s.

You must hate Mark Twain’s work with the burning passion of a thousand white hot suns.

And Herman Melville, who’s not averse to a bit of dialect in “Moby Dick”.

And Shakespeare… (“To the mines! tell you the duke, it is not so good to come to the mines; for, look you, the mines is not according to the disciplines of the war: the concavities of it is not sufficient; for, look you, the athversary, you may discuss unto the duke, look you, is digt himself four yard under the countermines: by Cheshu, I think a’ will plough up all, if there is not better directions.”)

And DH Lawrence, and Burns, and Stevenson, and Zadie Smith and VS Naipaul and Amitav Ghosh…

Yeah, I’m starting to think that our re-reader has got the point, guys. lol. Reading the article, I was going to comment on the anti-dialect thing myself until I saw how much the rest of you had. I’ll just leave it there. I loved this book. I loved this movie, too, even though it ran differently but toldthe same basic tale. The main issue that I had was the part of the review that stated that the molestation was taken right from a pamphlet. There is also “Write what you know.” Assuming one has never been molested, I think that it would be pretty disingenious of King to act as if he knew exactly what he was talking about. Also, those things are in the pamphlet for a readon and that reason is…because those are very typical of victims of sexual abuse. So, I don’t really see a problem with how he described it. It was harrowing nevertheless.

I’m working on finishing a novel, much of which involves compressing a lot of back story as well as doing what I can to make it palatable. (Making a lot of it into dialog.) It develops and foreshadows inexplicable events in the present and all leads to a major plot twist in the climax, so I don’t want to just ax it.

I found this review by searching based on my sense that Dolores Claiborne seemed to be pretty much all backstory. I don’t think anyone would spew an entire novel worth of personal events in one sitting unless they were wandering around a bus station at three a.m. gibbering insanely. I had the sense that the book was regurgitated quickly, which is kind of what the narrator does despite it being way too long to be quick, and I felt that it pandered to women’s issues deliberately.

Reading your review in relation to King’s mother, I am probably wrong about that. I wonder if maybe his mother spoke much like Dolores? I could imagine him wanting to speak for her and many like her in a literary “literal” sense. That said, when I read it some time ago I wondered if it might have been a single draft or nearly single draft writing.

I tried to read this when it came out, but a few pages of dialect put me right off. Today I finally read it, in one sitting, and loved it. True, I think King goes in too much for the over-worked home-spun turns of phrase (a frequent irritant in his books) but the narrative swept me away. Oddly enough the “Atropos” line and the daughter’s note also jumped out at me as over-written. Oh well. Gerald’s Game next! Hope the little girl in the pink striped dress comes out OK.