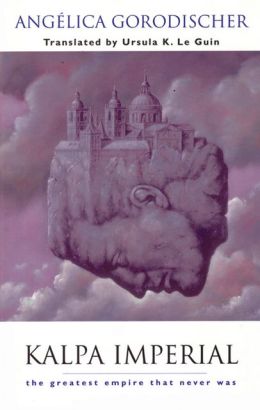

Here’s the first sentence of Angélica Gorodischer’s Kalpa Imperial: The Greatest Empire that Never Was, translated from the Spanish by Ursula K. Le Guin:

The storyteller said: Now that the good winds are blowing, now that we’re done with days of anxiety and nights of terror, now that there are no more denunciations, persecutions, secret executions, and whim and madness have departed from the heart of the Empire, and we and our children aren’t playthings of blind power; now that a just man sits on the Golden Throne and people look peacefully out of their doors to see if the weather’s fine and plan their vacations and kids go to school and actors put their heart into their lines and girls fall in love and old men die in their beds and poets sing and jewelers weigh gold behind their little windows and gardeners rake the parks and young people argue and innkeepers water the wine and teachers teach what they know and we storytellers tell old stories and archivists archive and fishermen fish and all of us can decide according to our talents and lack of talents what to do with our life—now anybody can enter the emperor’s palace, out of need or curiosity; anybody can visit that great house which was for so many years forbidden, prohibited, defended by armed guards, locked, and as dark as the souls of the Warrior Emperors of the Dynasty of the Ellydróvides.

I quote it in full because what was I going to do? Cutting this sentence would do at least three terrible things:

- it would break that breathless, intoxicating rhythm

- if I cut the end, it would strip the sentence of meaning—the conclusion demanded by the insistent now that… now that… now that…

- if I chopped out a piece of the middle, the sentence would lose the repetitions that create a sense of temporal entanglement.

By “temporal entanglement” I mean that Gorodischer’s sentence tells us there is nothing we do that does not have a history. Teaching and archiving, sure, but also arguing, singing, fishing—each has a past. Every now is a now that.

This knotting of time is probably the most striking type of entanglement in Kalpa Imperial, but it’s certainly not the only one. This is a collection of linked stories, each complete in itself but entangled with the others through the theme of empire and the tone of the storyteller’s voice. In the stories, again and again, we see individual lives tangled up in imperial history: the curious boy Bib transformed into Emperor Bibaraïn I in “Portrait of the Emperor,” the merchant’s daughter who saves an emperor from an assassin and then marries him in “Concerning the Unchecked Growth of Cities.” And people are entangled with one another, through love, rivalry, and kinship. But although Kalpa Imperial contains many fascinating human characters, it’s the cities, in all their unchecked growth, and the empires, as they rise and fall, that provide the real drama of these stories.

Angélica Gorodischer has made me think about character: what a character is, and what it means to be invested in the idea of character. She’s made me think about repetition—for Kalpa Imperial is embroidered with patterns that echo each other like arabesques. But most of all, she’s made me think about entanglement: how the past knots itself into the present, and how tightly form and content can be bound together. Form is content, some people say, and that may be true of everything, but there are some works that make us gasp as we recognize it. Kalpa Imperial is one of them. “[Y]oung people argue and innkeepers water the wine and teachers teach what they know and we storytellers tell old stories and archivists archive and fishermen fish”—human life rushes at you in that sentence, the lives of people woven into language that’s unbroken yet full of knots.

The knots are the persecutions, the secret executions that happen no longer, as we are living in the time of the now that. In saying now that, the storyteller appears to loosen the knots, but in fact she ties them tighter. Entanglement is a haunting.

Sofia Samatar is the author of the novel A Stranger in Olondria, available now from Small Beer Press. She also edits nonfiction and poetry for Interfictions: A Journal of Interstitial Arts, which is currently fundraising in order to expand its online offerings.