Though we’ve mostly been covering stories published in the past several years, there are also a wealth of older books that fit comfortably in the “mainstream/queer/speculative” Venn-diagram—some by writers whose names are pretty well-known, like Sarah Waters. Waters has received quite a bit of recognition since her first novel was published in 1998; she’s been the Stonewall Award “Writer of the Year” twice, for example.

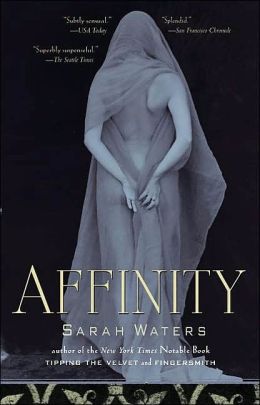

And when I was thinking of books to cover for this year’s Extravaganza, I definitely thought of Waters and one of her novels: Affinity, which was published around fifteen years ago.

Spoilers ahead.

Affinity is Waters’ second novel, following the acclaimed Tipping the Velvet. Both are historical novels about women who love women, set during roughly the Victorian era, but Affinity happens to revolve in part around the burgeoning field of spiritualism—so, it’s got ghosts and psychic phenomena that add a cast of the speculative to the whole endeavor. (And some folks argue that historical novels are a cousin to sf anyhow, so… I’m counting it as relevant to our interests.)

Affinity begins with two narratives: one of a young female spirit-medium whose séance goes wrong and ends with her in legal trouble, Selina Dawes, the other of a young woman who has attempted suicide and is being guided through a “recovery” by her mother, Margaret Prior. Margaret is our protagonist, a sharp-witted woman who has, we find out, previously had a love affair with the woman who ended up marrying her brother. It is this, not her father’s death, that lead her to attempt suicide; and now, as the novel opens, she is acting as a “Lady Visitor” to Millbank Prison as a sort of penance. Her visits are intended to bring guidance and comfort to the harshness of the women’s wards—but instead, she meets Selina Dawes, and begins a treacherous relationship with her.

The atmosphere in Affinity is perhaps the thing I appreciated most about it: a slow, subtle, steady build from the mundane cruelty of Victorian prisons and the home life of a “spinster”-age woman to the haunting desperation of Margaret’s love affair with Selina, the dark and consuming presence of the supernatural that evolves alongside it. Waters has a real skill for the creation and maintenance of oppressive atmospheres and stifled passions; the tension seems to ooze off of the page, particularly near the end of the text. It’s got a subtle eroticism built out of the brush of fingertips over a wrist and the mention of kisses—there’s precisely zero “sex” on the page, but this is nonetheless a sensual and intense story.

Part of this, of course, is thanks to her facility with historical detail and voice: Affinity is composed of a set of diary entries, primarily from Margaret but also including some from Selina, pre-incarceration—and all of these entries read pitch-perfect to me. Waters captures well the cusp of technology and modern society that these women have crossed, alongside the social pressures and restrictions that each struggles against, particularly the wealthy, isolated, and suffering Margaret. As she watches her old lover, Helen, interact with her own brother as wife and mother to his children, Margaret’s pain is clear; so is her passion, when she confronts Helen about abandoning her and her “kisses.”

When one gets used to reading so many texts in which sex is the primary defining moment of identity-formation for a queer individual, it’s fascinating to take a step backwards and read one in which genital contact is the least of the indicators of passion between the characters on the page. Interestingly enough, Waters’ first novel Tipping the Velvet is full of detailed, erotic, passionate sex between Victorian women—so it’s not, also, that she reduces historical sexuality to longing sighs and the brushing of hands. It’s just that this text offers an alternate viewpoint, from the diary of an upper-middle-class woman who does not have the opportunity, in the course of the novel, to engage in acts of physicality with other women… But who nonetheless is clearly, intensely, and sensually attached to women, to their love, and to relationships with them.

I like having that as part of a history and an identity, as well: the role of emotional intimacy in sexuality, and the different forms relationships can take.

Of course, Affinity is also a remarkably sad novel in the end, though I don’t think this places it necessarily in the genealogy of “tragic lesbian love stories.” On the other hand, it’s clearly referencing the trope—which happened to develop during the self-same period the book is set in… So, perhaps I also shouldn’t dismiss it entirely. Regardless, I sometimes like a good tragic tale, and Affinity does a wonderful job of wrenching at the heartstrings. It’s impossible not to ache with Margaret, to feel equally betrayed, in the end; she wanted to believe—and so as a reader did I—that it would all turn out fine.

But if the reader pays attention throughout, it’s clear that there is a game being played. Though we desperately want for Margaret to be able, in the end, to run away with Selina to Italy, it is also clear between the lines that Selina is not at all the person Margaret perceives her to be. That building tension is another unsettling part of the reading experience—as the ghostly encounters build, so too does our suspicion that something is not as it seems. In the end, the whole thing is revealed to be a clever scam designed to free Selina and reunite her with her actual lover: Ruth Vigers, who has come on as Margaret’s maid.

So, there are two women who run away together. And yet we’re left with a sense of hollowness, of betrayal, capped off by what we assume to be Margaret’s final diary entry before she kills herself—this time, successfully. It reads, in the end, as a sort of tragic mystery-novel; what one takes for a romance or a supernatural yarn at first turns out to be a whodunit, with the protagonist as the victim. It’s a clever bait and switch, one that I found effective and upsetting. Though we know it won’t turn out well, it still hurts to be right.

Waters is a talented writer, particularly working within her preferred time period, and Affinity is a strong novel, atmospheric and dark. It’s grounded in the casual cruelty of human beings to one another—particularly women to women—as well as the potential passions between them, rendering each in gripping detail. The novel occupies an uncomfortable grey area between desire and death, and while there’s certainly a history of that being a problematic queer fiction trope, it can also be a powerful literary pairing. In this case, I think it works—it’s tragic and sharp and unpleasant, but also feels quiet real and represents a part of historical experience and identity that I appreciate seeing on the page. And if you like it, I also recommend giving her other novels a look, though they’ve got a bit less in the way of ghosts.

Lee Mandelo is a writer, critic, and editor whose primary fields of interest are speculative fiction and queer literature, especially when the two coincide. She can be found on Twitter or her website.