A little over two years ago, I interviewed Keith Rosson about his 2021 collection Folk Songs for Trauma Surgeons. The subject of our conversation gradually shifted to encompass the apocalyptic, and Rosson said something that puts a lot of Fever House into perspective. “Maybe every generation feels like theirs is the End Times, but honestly, the scenario we’re currently in alarms me the most,” he said. “It’s a slow burn, but we’re right in the middle of it, you know? Hold tight while you can.”

[Content warning: gore, body horror]

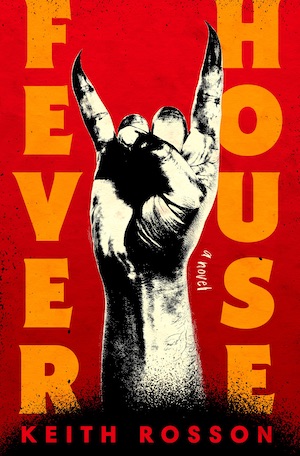

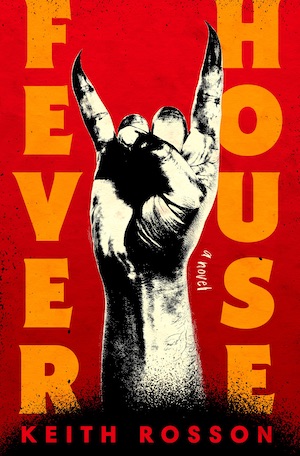

Fever House, Rosson’s new novel, is a panic attack of a book. It begins in the place where crime fiction and horror storytelling converge—think Margaret Killjoy’s Danielle Cain books, or Chuck Wendig’s Miriam Black novels as a point of comparison. Hutch Holtz and Tim Reed, functionaries working for Peach, a Portland, Oregon crime boss, are dispatched to shake down Wesley, a man who’s thousands of dollars in debt to their employer. When they find him, they discover that Wesley has somehow come into possession of a severed hand—and not just any severed hand, but an especially sinister one, and one that seems to instill a violent miasma in anyone near it.

“Hutch finally can’t stand it anymore. The noise is just too much, the snarl of it. The bloody clamor in his brain. He reaches over, grabs Wesley’s skinny thigh and squeezes as hard as he can, which is pretty hard. Wesley screams and bucks and Hutch feels good for a second.”

Had this been the basic premise for the novel—two men good at inflicting pain who are slowly corrupted by something that ratchets those tendencies up way past 11—it would have been a memorable read all its own. But it might not have been enough to sustain a narrative that clocks in at over 400 pages, as Fever House does. As Hutch and Tim’s night goes from bad to worse to the stuff of nightmares, Rosson expands the scope of the narrative—first subtly, then significantly.

Buy the Book

Fever House

Right about now is where I’m going to drop in a spoiler warning; having read this novel with little sense of where things were going, I found the experience dizzying, but in a good way, and if you’d prefer to go into this relatively cold, I won’t be offended. (See also: the “panic attack” allusion above.) There’s a lot that I enjoyed about this novel and a few things I found unwieldy, but in the same way that I find aspects of a lot of David Mitchell’s novels unwieldy but would much prefer them that way than with the unwieldy bits sanded down.

Spoilers follow.

Early on, Rosson drops hints of something much larger going on here regarding a government program dubbed Operation: Heavy Light. That turns out to be an off-the-books agency involved in things like remote viewing and occult artifacts; two agents from this organization, Bonner and Weils, are also tracking the severed hand, aided by visions—some straightforward, some impenetrable—by a figure known only as “Saint Michael,” who might be an angel. Saint Michael is also being repeatedly tortured by an agency higher-up in order to get useful information. (Between Rosson’s novel and Craig Clevenger’s Mother Howl, 2023 is shaping up to be the year of weird angels in fiction.)

Gradually, the narrative expands even further, as the hand’s effects spread beyond a few people and begin causing an uptick in violent incidents throughout Portland. (Also, it raises the dead, in one of the more understated zombie apocalypses in recent memory.) Rosson also introduces the novel’s two most likable characters: Nick Coffin, periodically hired by Peach to find rare objects, and his mother Katherine Moriarty. Katherine and Nick’s late father Matthew were both in The Blank Letters, a beloved indie-punk band that released a handful of albums before effectively imploding.

There’s a fair amount in Fever House about The Blank Letters’ heyday, which turns out to be more relevant to the plot than it might initially seem, but which also makes Katherine and Nick feel more three-dimensional. The same is true for many of the characters: Hutch is someone who makes money through violent acts, but Rosson spends time explaining how he came to be that way; this is also the case for the two agents chasing down the hand, both of whom turn out to be more idiosyncratic than their roles as agents of a sinister conspiracy might suggest.

Again, Fever House can be an unwieldy book to read. Because of the way that it’s structured, it takes a little while for Katherine and especially Nick to come into focus. Given that the two of them, and the bond that they have, form the emotional core of the novel, that can feel a bit disconcerting. On the other hand, the film Fargo took its time introducing Marge Gunderson and that worked out all right, so it’s not like there isn’t precedent for this kind of thing, narratively speaking.

What made Fever House compelling for this reader was the way the stakes kept getting higher and higher. Had this been a Portland-set supernatural noir, I’d have been on board for that, but the story Rosson is telling here goes beyond that, reckoning with institutional corruption, authoritarian impulses, and the classic trope of humanity developing technology that might result in its ruination. Rosson’s novel plays out like a nightmare—one that’s nearly impossible to put down.

Fever House is published by Random House.

Read an excerpt.

Tobias Carroll is the managing editor of Vol.1 Brooklyn. He is the author of the short story collection Transitory (Civil Coping Mechanisms) and the novel Reel (Rare Bird Books).