Puloma Ghosh’s short story collection, Mouth, pulses with relatability. The taste of awkward social maneuvers and restless impulses form a sweet nostalgia for a younger, weirder time when my body didn’t hurt from just getting out of bed. Whether Ghosh writes about obsession, compulsion, care, aloneness, it’s easy to fall into the rhythms of her characters, particularly the disconnected twentysomething protagonists who evoke the familiar mix of hard-headed rebelliousness and twee precociousness that defines so many MFA aspirations.

This isn’t necessarily a criticism. Mouth is a polished debut, bristling with neat prose and nuanced excursions into speculative presents and futures. The collection is packed with bangers, but at times, feels like Ghosh is making efforts to tame and contextualize her weirdness for a finicky literary audience that might be allergic to anything remotely close to the dreaded subworlds of genre. “In The Winter” felt most guilty of this—the shortest story in the collection which was decidedly not for me. “Natalya,” presented as an autopsy report, is a well-formed experiment with format and tone, but more often than not, felt like a perfunctory and unremarkable post-mortem of a relationship that wasn’t quite on par with the rich peculiarities of its bookmates.

“Anomaly” is one such oddball—a seemingly straightforward tale of online dating with a surreal twist, and possibly my favorite in the book. The protagonist works an unfulfilling call center job while encased in a soundproof glass cubicle—a logical extrapolation of our existing surveillance-riddled reality—and half-heartedly spends her spare minutes swiping and ignoring bad icebreakers. She’s also living in a world struggling with a time war rife with spies and timeline-meddling—things usually confined to a grand sci-fi premise—which Ghosh smartly downplays to become an unnerving but very effective contextual backdrop. And when our protagonist does land a date, her would-be paramour suggests going to visit an anomaly, a vaguely menacing tear in spacetime that has inexplicably become a corny tourist attraction supervised by the government. It’s a lovely examination of absurdity and human hubris; after all, what could possibly go wrong at a cosmic aberration that has its own mini-train and fried cheese curd vendor?

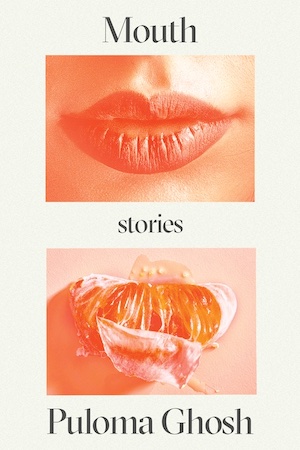

Buy the Book

Mouth

Another standout is “Leaving Things,” which does a tremendous job of evoking aloneness and resilience in a place slowly being emptied of human life. The protagonist, a trained vet, attempts to save a pregnant wolf—a bizarre act given that her town is subject to strange and increasing wolf attacks—but is only able to save what she believes is the baby in its belly. “Leaving Things” on its face isn’t a complex story; it’s easy to grasp the symbolic connections that Ghosh offers about the town’s disappearing women, duty of care, and autonomy. It’s an almost comical account of the protagonist’s predicament where Ghosh doesn’t quite follow the predictable trajectory of a love story, nor does she navelgaze on the unexpectedness of surprise motherhood, but builds something fresh and strange and distinctly her own.

When Ghosh is on fire, her prose is incandescent with the heat and bite of personal conviction. What I like best is her treatment of impulsiveness; her best characters are truly carpe diem’ing their way to their most authentic selves in the most bizarre circumstances. Occasionally, though, it’s possible to see where perhaps an early reader may have asked for a little more clarity, or a smidge more exposition or context, to the detriment of Mouth’s overall vibe. It reminds me a little of an old n+1 essay from 2010, MFA or NYC, specifically the increasingly uniform neatness and relatable appeal of MFA program output, while also making me neurotically question my own biases as a reader and critic. Stylistically, Ghosh’s prose also exudes a neat efficiency, but without eroding the sincerity and eccentricity of her ideas, especially when her characters are being fervently horny as is befitting their youth. But in places, like some of the flashbacks in “Lemon Boy,” I’m yanked out of Ghosh’s distinctive cadence by curiously stiff phrasing and the sense of an invasive formality and the diminishing sort of neatness and accessibility laid out in that n+1 essay. Ghosh is better than this, and I hope she knows it.

Still, going down into that New England basement is visceral. In “Lemon Boy,” I am reading the true words of a real-deal Masshole who knows that the real horror of unfinished-basement college parties in Cambridge and Somerville isn’t damp wood or rats, but the monstrous indifference of the people around you.

Mouth is bookended by two of Ghosh’s most powerful stories, “Dessication” and “Persimmons.” The first is a delightful take on coming-of-age stories and identity, where the protagonist slowly befriends an undead girl—another Indian girl—at their small town’s ice rink; there’s also the silhouette of a larger world here that practices conscription for men, which Ghosh skillfully keeps just out of view. It’s a ruthless little story that wields teen-girl figure-skating as a weapon, as well as the inescapably long shadow of immigrant mothers and their legacies; to enter Ghosh’s world through this ice-wrought portal feels like an exquisitely cold, sharp baptism.

On the other end, “Persimmons” is still a mother-centric narrative tied up in responsibilities and legacies, but full of untouchable life and old, decaying structures waiting for the moment of relevance. Ghosh takes the smalltown claustrophobia in “Dessication” and reshapes it to fit a planetary setting in “Persimmons.” The result is a remarkable escalation of tension as the protagonist Uma prepares to fulfill a prophecy that bypassed her mother. Here, Ghosh is extra evocative with places and textures, mirroring her character’s farewell to the physical world. This wet, fleshy rite of fulfillment is how I leave Mouth—a violent burst of obligation, resentment, and vindication. It’s a very different sibling to how the themes are explored in “Dessication,” an almost joyful return to what feels like Ghosh’s raw voice, and a fitting end to a formidable debut.

Mouth is published by Astra House.