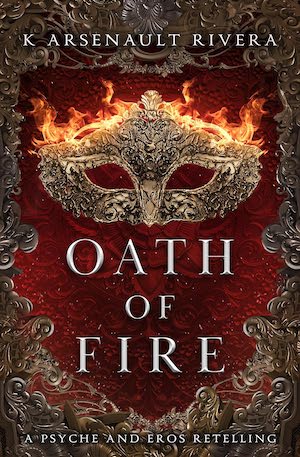

K. Arsenault Rivera’s debut trilogy was an epic fantasy and a queer love story that was interested in the apotheosis of its arguably human protagonists—larger-than-life heroes—into gods. Oath of Fire is a different beast, though it retains Arsenault Rivera’s interest in the interaction between mortal concerns and more-than-mortal powers. It sets itself in New York, and gives us a retelling of the tale of Eros (better known, perhaps, in the Latin form as Cupid) and Psyche.

The story of Cupid and Psyche was given its canonical form in Apuleius’s Metamorphoses, also known as The Golden Ass, a Latin novel which dates from the second half of the second century CE. Apuleius’s version is thoroughly heterosexual, and just as thoroughly saturated with the misogynistic norms of his society. It is also very much concerned with hierarchy and status: Psyche, though held by Cupid to be his wife, is considered as a slave by Venus, whose position is that their marriage is invalid as much because of the status difference between god and mortal as the lack of Cupid’s father’s permission and the lack of witnesses to the wedding. (Apuleius plays with Roman legalistic logic.)

Arsenault Rivera discards the misogyny and prefers Greek names to Latin. In Oath of Fire, Psyche is still the youngest of three sisters. Her elder sisters are both more successful than she is, in conventional terms and in her own eyes. Psyche wants to help people, though (apart from her cat) she lives an isolated life. She has a small following as an influencer, making regular videos. Her only friends are fellow players of an online multiplayer game, most of whom don’t even know her real name. She’s driven by compassion, by the urge to help and be useful: As the novel opens, she’s employed as a therapist—a job she soon loses, thanks to a misunderstanding, rooted in Psyche’s deep urge to help, that means it looks like she outed a trans patient to said patient’s parents. Depressed, unemployed, and at loose ends, when she receives a peculiar party invitation from an online connection —a very very hot guy—who calls himself Zephyr, and who says he wants her to help his friend, it only takes a little persuasion to get her to go.

Buy the Book

Oath of Fire

But this is no ordinary party. Instead, Psyche finds herself transported to an arcane court, full of ecstasy and terror, equal parts dream of desire and nightmare of terror and excess. It is here Arsenault Rivera marries the most sensuous and the most ruthless undercurrents of Greek mythology to modern fantasy’s more lush and erotic interpretations of faerie courts. There are, we learn, many such arcane courts, and their inhabitants are bound by laws that are part of their very being, such that they can’t break them and live. The gods are bound by oaths and compacts, which is a problem—for when Psyche’s escort, Zephyr, is shown to be in breach of his compacts, the protection his presence affords her is stripped from her. She’s prey for the court’s inhabitants, to be a sacrifice to its ruling lady, until Eros intervenes to save her. Eros here is feminine, beautiful, borne aloft on wings of flame, masked and armoured. Psyche finds her fascinating. And attractive.

Eros wants to see her again, to talk with her even though she claims that she has no need of Psyche’s services as a therapist. In order for this to happen, they must swear an oath to each other. “[Y]ou’ll need stronger protection to see me regularly,” are Eros’s words. “If you haven’t noticed, Court is… intense. Too intense for most of your kind.” The oath (an “Oath of Fire”), sealed with a kiss, binds them: Eros pledges love and protection, Psyche to heed Eros, and Psyche is warned to not look under Eros’s mask. And after this dramatic quasi-marriage…

…Well, they essentially start dating. Eros begins turning up in Psyche’s everyday life, and Psyche finds that the presence and interest of this fabulous otherworldly warrior gives her confidence to believe in herself and her capabilities in ways she hadn’t, before. Meanwhile, Psyche’s kindness and skills at getting people to open up cause Eros to acknowledge her own emotions. Eros invites Psyche further into her life and the life of the Courts, leading to Psyche learning more about the kinds of things that Eros has done in her very long life than, perhaps, she was entirely ready for. The push-and-pull interaction of the superhuman with the mundane—the intrusion of Eros’s fantastical self and world into Psyche’s everyday life, and the intrusion of Psyche and her human reactions into Eros’s context—is fascinatingly well done, and mirrors (albeit, as this is fantasy, in very exaggerated form) the interpenetration of realities and expectations, the compromises and the unexpected shocks, when two very different people begin a relationship with each other.

But this is a Cupid-and-Psyche story, so the course of their developing relationship is ultimately to be sorely affected by the jealous fury and vengeful spite of Aphrodite, here playing the role of abusive, controlling parent. Psyche’s sisters play, here, much more supportive roles than they do in Apuleius’s version: It is Psyche’s subconscious that casts them as doubting figures, the avatars of her insecurity, where in Apuleius they manipulate her against her own best interests. (It bothers me a little that this appears to be a world without Greek mythology: Psyche, despite having Greek ancestry and being a video game geek, relates none of what happens to her to the myths of Greek antiquity.)

This is a very intimate novel, concerned with interiors and emotions. It uses the strangeness of the Courts and of Eros herself to look at the estrangement that is that glittering period of early-relationship attraction, the erotics of limerence: The mask becomes a metaphor for uncertainty of knowing another person, the boundaries that every relationship has for trust and privacy. It draws itself larger than life, but it uses those larger than life elements to look at very common, ordinary things: isolation, anxiety, insecurity, the anomie and atomisation of having all your friends live in the internet, falling in love with someone you think is out of your league, the difficulty of relating to family, trust and mistrust, truth and power, cruelty and kindness.

Aphrodite’s interference in Eros and Psyche’s love story has especial resonance in a queer retelling: Eros steps out of the box her parent has designed for her, to claim the right to direct her own life, and faces rejection and the rejection of her chosen partner in consequence. Once again, K. Arsenault Rivera gives us something that possesses uncomfortably familiar power, though cast in fantastic terms.

Oath of Fire is also a novel that embraces the erotic. That is not to say it puts a great many sex scenes on the page, but rather that it sinks deep into sensuality, dwells lovingly on somatic sensation, on taste, on touch. Food and fragrance recur. It fills the world of the senses, portrays sexuality without shame, embraces a queered erotics of the body, with its emphasis on hands, on movement, on non-sexual touch that carries an erotic charge as well as the frisson of intentional, sexual touch. Danger, strangeness—estrangement from the ordinary—takes on erotic potential. The romance between Psyche and Eros lives in the orientation and instinctual reactions of their bodies, linked by the fiery oath Eros insisted upon, as much as in their speech or acts. Erotic but rarely explicit, yet deeply entwined in the flesh. A novel of embodied longings, consummated by degrees.

It’s a fascinating interpretation, and an interesting, compelling novel in its own right. I’m glad to have read it.

Oath of Fire is published by Forever.