A dead man lives in Temporal Crescent. A Mr. Andrew Pyewackett, to be precise. He passed away seven years before the events of The Devil’s Apprentice, but he’s stuck around since to be sure that the unholy house he spent his lifetime looking after is left to someone sensible, someone undaunted by its particular… idiosyncrasies.

He has the ideal man in mind—Bartlemy Goodman, of no fixed above—alas, no one has been able to find the fellow, and in the period his lax lawyers have been looking, Pyewackett has gone to pieces. Quite literally. As he admits, “I simply can’t go on like this. […] Flesh and blood won’t stand it. Let’s face it, they aren’t meant to. Look at me, I’m already falling to bits—every time I remove my socks several toes fall off. I need to get out of this body and move on. Arrangements will have to be made.”

These arrangements are as strange as the circumstances which made them a must. Pyewackett instructs the family firm to appoint Penelope Anne Tudor—Pen to you and me—as interim executor of his remaining estate. She’s to move into the adjoining property, which comes complete with a brilliant butler and its very own pair of haunted falsers, the better to continue the search for the lost legatee.

Thing of it is, Pen’s only thirteen, and her grandmother will never go along with this madness… will she?

She would never be allowed to stay in Temporal Crescent and do her job. And she wanted to. She wanted it more than anything in her life. It was maturity, responsibility, freedom. She had decided she wasn’t worried about the danger element—a house surely couldn’t be dangerous, with or without a front door. Whatever might happen, she would handle it.

If she got the chance.

She gets the chance.

Let us pause before we talk about the plot proper to consider this: one of my only problems with what is otherwise a magnificent new novel. Pen’s gran is an absolute pushover. She takes precious little convincing in the first instance, is largely absent after the fact, and when there’s a murder outside 7A several weeks later, dear old Eve expresses her regrets and then simply goes about her business. Which seems, in short, to be shopping.

This is one of the genre’s peculiar problems. Reminiscent of modern horror’s struggle to strand its characters in isolated environments in a world where such places are truly few and far between, the YA narrative must arrange, often implausibly, for its pubescent protagonists to be let loose by the adults in charge of their care; adults who would in all probability spoil the fun for everyone. In The Devil’s Apprentice, Jan Siegel simply dismisses the need for a decent rationale as to why Pen and her pals can run riot, and that did bother me a bit.

Besides this, though, The Devil’s Apprentice is fantastic fun, especially once we find out what the house is all about. No. 7 Temporal Crescent isn’t haunted, as it happens. Instead:

“It’s something called a space/time prison,” Pen said. “I don’t know what that is, but all the doors open on different bits of the past, or magical dimensions, and if you go through you’ll get lost, sort of absorbed into history. Like if you’re in the eighteenth century, that’s where you think you belong. It stops people going around changing the course of events.”

As soon as Pyewackett passes on, Pen sets about investigating No. 7 in earnest. By the time Gavin Lester let himself into the adjoining quarters she’s already been attacked by a velociraptor, so Pen is happy for him to help. He’s looking for Bartlemy Goodman too—Gavin believes Bartlemy may be the man to teach him how to be Great Britain’s best chef—as is Jinx, a little witch who comes a-calling because she’s intercepted whispers from double-dealing demons about a unique job opportunity.

No one believes in the Devil any more. He went out of fashion with wimples and witch-trials, made a brief comeback with the powdered wig, the bal masque and the Marquis de Sade, popped up in the London smog somewhere between the crinoline and the bustle, and vanished for good into a world of kitsch horror films in the mid/late twentieth century. Evil went on, of course, but Evil is made by humans; we need no supernatural help for that. But there is someone who feeds off our evil—who feeds it and feeds off it—the Rider of Nightmares, the Eater of Souls, the God of Small Print, and if he no longer wears horns and a tail that is merely a matter of style. Modern thinking belittles him, superstition touches wood for him, children dance around his maypole—but never widdershins, always with the sun. He hides in folktale and fear, in legends and lies—don’t speak his name, or he may hear you, don’t whistle, or he may come to you. If you believe in fairies, don’t clap, for there are darker things than the sidhe in the World Beyond Midnight. Call him a myth, call him a fantasy, for myth and fantasy do no exist.

He exists.

He indubitably does in The Devil’s Apprentice, and indeed, he’s looking to appoint his eventual successor, who he’s decided must come from the mortal realm.

To be completely clear, Jinx doesn’t want the job: she wants to stop whoever does. Because better the devil you know, you know?

She and Gavin and Pen are in any event a terrific trio of troublemakers who work wonderfully as one. Pen is our resident skeptic. Pyewackett hiring her “was the most magical thing that had ever happened to her, except she didn’t believe in magic. Unlike her friends, she didn’t read fantasy books—in fact, she read very little fiction at all since she couldn’t see the point of it, though her grandmother had ensured she had a basic knowledge of all the classics. But Pen preferred facts. […] In her view, imagination just got you into trouble.” Jinx the witch is by definition Pen’s polar opposite, though they get on pretty well for all that, whilst she and Martin are at odds with one another from the first, which needless to say leads to some smartly barbed banter.

In Jan Siegel’s capable hands the entirety of The Devil’s Apprentice is rather smart, in fact. The novel’s long chapters are punctuated by ominous interludes set elsewhere and elsewhen which do a great job of enlivening the story’s more mundane moments… though there are few of these, in truth. Accordingly, the plot is a joy: the premise all potential—above and beyond what goes on in this novel—and in execution even better, equal parts chilling and thrilling.

Take, say, The Graveyard Book by Neil Gaiman as a base. Fold in a little K. J. Parker, perhaps, and fill with Jasper Fforde a la The Last Dragonslayer. Season to taste with finely ground J. K. Rowling and serve with a generous helping of Diana Wynne Jones’ wonderful whimsy. It may be that I’ve been mainlining The Great British Bake Off in recent weeks, but Gavin—the would-be cook of this delectable new book—would approve, I’m sure.

Jan Siegel has been silent, sadly, since the unceremonious sinking of her Sangreal trilogy in 2006. A young adult fantasy for all the family certainly wasn’t what I expected from her new novel, but with a hint of the sinister and a smidgen of silliness, it’s such bloody good fun that it’s a pleasure most piquant to welcome her back to the business of witty literature.

Don’t go anywhere, eh? Pretty please with a temporal cherry on top!

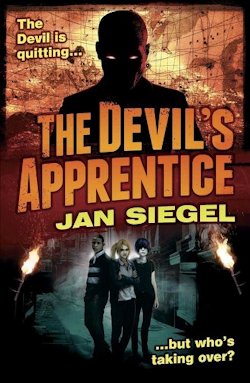

The Devil’s Apprentice is available now from Ravenstone.

Niall Alexander is an extra-curricular English teacher who reads and writes about all things weird and wonderful for The Speculative Scotsman, Strange Horizons, and Tor.com. On occasion he’s been seen to tweet, twoo.