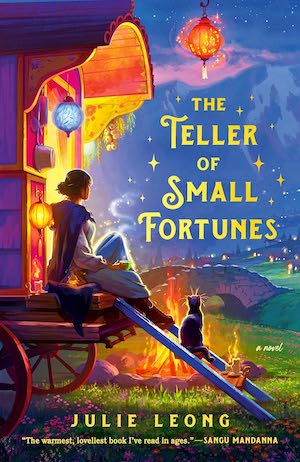

The hero of Julie Leong’s debut novel, The Teller of Small Fortunes, knows better than to tell big fortunes, the kind of fortunes that shape destinies. Tao travels through the kingdom of Eshtara, lingering only a few days in each village. It’s a lonely life, but a safe one: If a village seems hostile to Shinn immigrants or magic-users, she can pack up her wagon and move on. She’s happy—kind of—with her itinerant existence.

But everything changes when two strangers on the road help her move a branch that’s blocking her wagon’s path. Tao tells a small fortune for Mast, that he’ll give his daughter a kitten soon. It turns out that Mast and Silt are on the road searching for that very daughter, who was kidnapped by raiders, and the trail has gone cold. Their hopes renewed, the two of them decide to travel along with Tao for a while. They acquire a cat. They meet a baker with unusual ideas. Suddenly, Tao has friends, travel companions, perhaps even—for the first time since she fled her home and her stepfather’s stifling expectations—something like family.

If romance novels feel like the author is looking you dead in the eyes while handing you a slice of your favorite cake (there’s only one bed; it’s a marriage of convenience; she’s a storm cloud and he is a sunshine), friendship novels are perhaps not trying to smash your dopamine receptors with quite the same force. But there’s a similarly iterative pleasure to watching a lonely character getting dragged willy-nilly into community. As soon as it’s established that Mast has a daughter, and the daughter is missing, you know that Tao’s in it with him for the long haul. Mast can hit people and Silt can steal things, so you know they will be hitting people and stealing things on Tao’s behalf, and you know she’s going to be overwhelmed by the new experience of being cared for by other people.

The pleasure of iteration lies in the different ways the author sticks with your expectations or spikes them, and Leong does plenty of both. On the one hand, yes, Mast punches some people for Tao, and Silt steals things for her; I was right to expect that. When trouble comes, for the first time since Tao’s early childhood, she doesn’t have to face it alone.

On the other hand, the road to being in community isn’t without its bumps. When baker Kina joins the group, Silt starts making eyes at her. I sighed wearily, not being much in the mood for a by-the-numbers background romance. Instead, Kina takes some time to think it over, then dresses Silt down for hitting on her just because she’s there. It rules. I love it when characters scold other characters for things the narrative has shown us but hasn’t quite named yet. Besides not feeling like Silt is genuinely into her, Kina doesn’t want to date him because she doesn’t think he’s genuine at all:

“You’re a macaron… They’re wonderful to eat, but you can’t make a meal of them, for they’ve no substance.”

“You think I’ve… no substance?” said Silt. He sounded bewildered and hurt…

“You’re all charm and flattery and coin tricks, Silt! You’re a great deal of fun to be around, but I have no idea what’s underneath it all.”

As defensive as Silt feels in the moment—he does the thing of trying to rally Tao and Mast to his cause, which I found so relatable—he ends up truly taking Kina’s feedback to heart. Silt begins to think more deeply about what makes a person of substance, and he tries to choose the way that kind of person would choose—which in turn opens the door to greater intimacy with the other members of this burgeoning family. Like community, character doesn’t just happen. We choose, and choose, and choose to build those things, and all our choices together with the choices of the people around us make a life.

SFF is at a fascinating point in its relationship to cozy (slash comforting, slash low-stakes) fiction. In these troubled times, many readers are starved for SFF novels whose stakes aren’t in the “save the world” tier; books whose protagonists don’t hold the fate of nations in their hands; books that reassure rather than unsettling; books where people are basically good and communities support each other and everything turns out okay. Julie Leong wrote The Teller of Small Fortunes to meet exactly this craving, as Ace’s publicity materials note: “Sitting at her father’s hospital bedside, Leong read any book she could find that was magical, comforting, and heartfelt. When she began to run out of cozy fantasies to read, she thought: Why not try writing one myself?”

Buy the Book

The Teller of Small Fortunes

Yet alongside this craving for comfort exists an equally powerful suspicion of that craving, and of the fiction that attempts to sate it. What rough edges are being smoothed over to give us that feeling of comfort? What have we readers done to deserve comfort in the first place? Does coziness require an abandonment of critical thought, temporary or long-lasting? If this world is a utopia, who has been left behind by it? Isn’t it the task of speculative fiction to confront and challenge us, and has not the author abrogated their responsibility by prioritizing warmth and coziness instead?

I’m not making fun of those questions. They’re big, important questions. But I also want to make the case that confrontation is by far the easier task. It’s no great feat of imagination to dream up a corrupt system. The system is easily imagined breakable because systems are easily broken. To imagine a system unbroken is to hold in your mind something impossibly vast; it is to consider every possible breaking point and strengthen it. And comfort requires good systems, I think. I am comforted by grilled cheese sandwiches and reliable nonfiction, which requires systems for food regulation and peer review.

If a writer is interested in comforting her readers, then, she can write her characters into unflawed systems; or allow them to exist within systems she and they acknowledge as imperfect; or opt her characters out of such systems altogether. At the start of The Teller of Small Fortunes, Tao has chosen the third path. She sticks to smallish towns where she won’t come to the attention of the regulatory body for magic-users. She doesn’t stay long enough to risk negative responses to what she can do. And if she encounters racist prejudice, she simply moves on. (It’s worth noting, though, that even this set of choices bespeaks the existence of political decisions that enable her to travel freely between villages.)

Only, it doesn’t work. It can’t. We are, as the poet says, each other’s business. When Tao makes the choice to be in community with Mast and Silt, she cracks open a door to being in community with more people, and more, and more, and then she’s caught up in the various systems and societies she had tried to exempt herself from. If we are going to be people in the world, we’re stuck being people with each other.

The Teller of Small Fortunes presents us with systems and people that are generally good—the world as we’d like it to be. Tao’s journey throughout this book is to learn that the people and institutions she has feared, the bogeymen of her childhood and her life as a traveling fortune-teller, are not as terrible as she thought. This will hit different readers differently, I suppose, but I found it comforting. The current real world is uglier and crueler than I hoped its inhabitants would choose to make it, and I found a true respite in spending some time in a world where the opposite is true. The Teller of Small Fortunes is sweet and silly and warm. If Leong’s goal was to offer heartfelt comfort to her readers, she’s achieved it in spades.

The Teller of Small Fortunes is published by Ace.