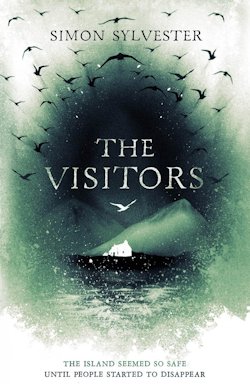

A contemporary twist on an old fisherman’s myth complete with an immensely atmospheric setting, a strong yet sympathetic central character and a missing persons mystery that’ll keep you guessing till all is said and done—and then some—The Visitors by Simon Sylvester has everything including the girl going for it.

For all it has to offer, Bancree has seen better days. As a remote island off the coast of Scotland—bleakly beautiful, to be sure, but truly brutal too—it and its inhabitants have been hit hard by the economy’s catastrophic collapse. “There was nothing on the island that wasn’t already dying. Half the houses were for sale. The island population numbered only a few hundred, and that dripped away, year on year.”

Little wonder, as the only booming business on Bancree is whisky, and Lachlan Crane, the son set to inherit the local distillery, is at best “a bully and a womaniser,” and at worst? Well. Time will tell. For him and for Flo.

Said seventeen-year-old has no intention of taking a job at the Clachnabhan factory when she finishes her final year. She’ll be leaving home just as soon as is humanly—like her former boyfriend, who beats her to it at very the beginning of The Visitors. A whipsmart character from the first, Flo knows that Richard isn’t the love of her life; still, she feels defeated when he makes a break for the mainland:

Going out with him was an escape—my route to freedom, a cord that connected me to the world outside. Richard had cut that cord, and I felt robbed and hollow, the cavern of my stomach writhing with tiny, wormy things. Frustration, envy, sadness. It should have me who’d escaped into a new life, drinking in bars and meeting new people. It should have been me doing the breaking up. The dumping.

One way or the other, the deed is done, and for a moment, Flo is alone; as alone as she’s ever been, at least. Then she makes a friend. Ailsa, one of the titular visitors, moves into the abandoned building a few minutes across the sea from Flo, and the pair promptly hit if off. Doesn’t hurt that Flo fancies Ailsa’s enigmatic father:

Each of us had something the other wanted. Ailsa craved community. I needed change. Between us, we had both. [And] every now and then, I’d glimpse her father in her face—just a little in the nose, in the peatbog eyes—and flush to think of him.

Their precious friendship is tested, however, when Flo finds out why Ailsa and John are here on Bancree. They’re desperately seeking someone, it seems: someone they believe to be responsible for decades of disappearances; for the fate of dozens of missing men and women—not least Ailsa’s mother—from all across the highlands and islands:

Now the clouds gathered weight and oozed menace. The air felt too thick. It was intangible and impossible to frame, but I couldn’t shake the feeling that something was about to happen.

Something is…

Stitched through all this—seamlessly, even—is a thorough and thoroughly subversive study of selkies: the subject of a school project inspired by “a strange, strange book” Flo finds in the local charity shop, which paints the seal people of coastal folklore as malicious, manipulative monsters as opposed to the pretty, submissive souls of most such stories:

The book told tall tales of selkie maidens luring sailors to their deaths by drowning, ambush or assault, stoving their heads in with rocks and oars, tangling them in nets and lines, holding them under. They cast spells, making people fall hopelessly in love with them, then fled, abandoning the stricken men or women to lifetimes of solitude, misery and suicide. In every page, I could feel the frenzy in the author’s voice, could trace the spite in every word.

Whether selkies represent the sinister “suppression of female sexuality” or people simply “needed these creatures to explain the events in their lives they couldn’t control,” Flo isn’t willing to accept an anonymous author’s account without question, so she asks a shennachie—a roving storyteller—if there’s any truth to these terrible tales.

Izzy’s answers—garbed as they are in an oilslick skin of fiction—are among The Visitors’ most magical moments… and this is not a novel light on highlights. It perfectly captures the qualities of life on an island, both appealing and appalling. Bleak as Bancree may be, insular and archaic as it is, “when there’s no one else here […] it feels like the island’s alive, just me and Bancree.”

Similarly, there’s so much more to Flo than the angsty outsider she’d almost assuredly be in other books. Instead, Sylvester strands her on the borderline between childhood and maturity, loneliness and love, leaving us with a young woman coming of age in two worlds at once, as forces beyond her ken pull her in drastically different directions. Flo is authentic, I think, and her development—which reflects that division brilliantly—is without question affecting.

Thus, though the story is something of a slow burn at first, there’s every reason to keep reading till the suspenseful mystery in its midst is made plain—the eventual resolution of which ties the various visages of The Visitors together tremendously well. All told, it’s an astonishingly assured debut, fit to put the fear of the deep dark sea into other authors, be they old hands at the shennachie profession or first-timers like Sylvester himself.

The Visitors is available in paperback February 5th in the UK from Quercus.

Niall Alexander is an extra-curricular English teacher who reads and writes about all things weird and wonderful for The Speculative Scotsman, Strange Horizons, and Tor.com. He’s been known to tweet, twoo.