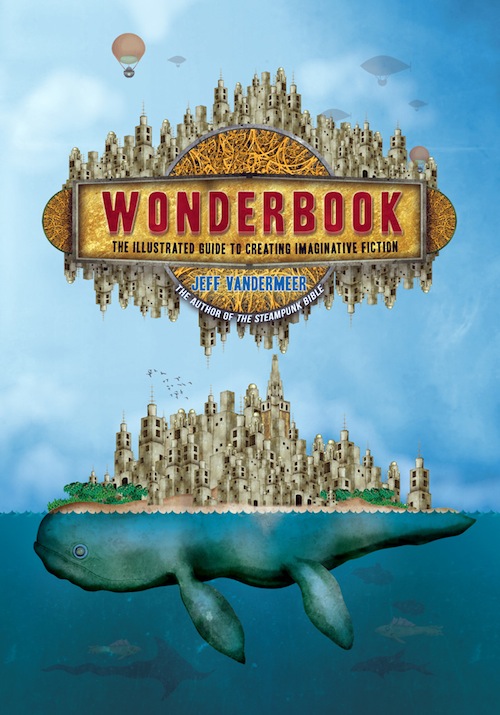

First released in mid-October, Wonderbook: The Illustrated Guide to Creating Imaginative Fiction by Jeff VanderMeer is a fascinating mélange of straightforward exploration of craft topics (plotting, characters, revision, etc.), strange and lovely art, sidebar interviews with popular writers, exercises and experiments, fantastical diagrams, and more—including a digital compendium off of the page at WonderbookNow.com. It’s an ambitious project, with a lot going on between the covers (and beyond).

Of course, the concept of a multimodal writing text snagged my interest straight away, particularly considering that I also appreciated VanderMeer’s earlier writer’s guide Booklife quite a lot. I was not disappointed, having taken the time to peruse and play around with Wonderbook. The sense of this book as organic, sprawling, and multiply voiced makes it one of the most “fiction-like” fiction writing guides I’ve ever seen; it also productively prods at the varying levels of the imagination involved in the process of writing instead of relying solely on naked words.

And the multiple modalities of the text aren’t just for fun—though they are, often, very much that. They function to explicate aspects of the process of writing fiction, taking advantage of various forms and tones along the way. The nontraditional approach to the writer’s manual VanderMeer takes, here, seems to me one of the most effective attempts I’ve seen at rendering the complex, contradictory, and often partially subconscious process on paper in a way that mimics visually and textually the “experience,” whatever that might be.

For example, each page is busy with colors, images, or diagrams; rarely is there just a whole block of black text on white background. And, somehow, that works. Rather than feeling put-upon or yanked around by the side-notes, I experienced them as little blips of extra thought, meat to chew on, that sort of thing. I suspect that’s because the design and layout of this book is thumbs-up great work. It would have been easy for the wealth of sidebars, little characters, and asides to clutter up the text.

Instead, they give it depth and breadth outside of the traditional chapter-and-subheading organized explorations that form the main heft of the book. (Also, seriously, the cartoon bits are kind of hilarious. For example, page 72.) The multimodal stuff—the art, the digital extras, the cartoons and visual renderings of amusing and functional metaphors—turns what could have been simply another interesting book on writing into a very good book on writing that provides a non-restrictive, imaginative, immersive experience for the reader.

And, considering that the implied reader is a beginning or early writer, that’s a valuable thing. To soapbox for a moment: too often, popular (and otherwise useful!) writer’s handbooks are presented as concrete, straightforward, and purely technical. This book, on the other hand, melds its explorations of technique with an organic, intimate sense of writing fiction as a whole—a sort of story creature, images for which appear throughout the book and were something I distinctly enjoyed. (The Ass-Backwards Fish [273] was a particular favorite of mine.)

Another thing that I appreciate in Wonderbook is that, though VanderMeer’s text forms the major body of the book, it is perpetually in dialogue with short essays by other writers, sidebar quotes that often contradict the exact thing he’s saying, and an entire cartoon whose purpose on appearance is to be the devil’s advocate for a given “rule.” Vistas of possibility in writing fiction opens up through these dialogues, keeping the book from being a study of one particular writer’s habits distilled into a one-size-fits-all methodology.

Which brings me to that main text. (It would be remarkably easy to spend an entire discussion just on the art chosen for reproduction here, or the diagrams drawn by Jeremy Zerfoss, or the function of the cartoon creatures. I’ll resist.) Specifically, I appreciated the conversational yet informative tone of VanderMeer’s work in the main chapters—it both welcomes and educates. By offering personal anecdotes and examples—the novel Finch’s opening is used to good effect on beginnings, for example—VanderMeer connects the reader to a solid exploration of what different components of the story-creature might do.

Much of the technical stuff is familiar—there are, after all, only so many ways to talk about dialogue—but it is always explicitly discussed as part of a larger organism. The focus on the organic and embodied nature of a “living” story, again, is the thing that Wonderbook hits on the mark: it is possible, as VanderMeer proves, to explore technical and mechanical aspects of fiction without discarding the greater object at the same time. The book isn’t just a series of anecdotes, after all—it’s a logically-organized guide to creating imaginative fiction, a guide designed to itself provoke inspiration and complex thought on the nature of writing stories. It, too, exists as a whole rather than a collection of parts.

There are certainly moments that stood out to me in the main text, as well. In chapters on character and setting, VanderMeer explicitly notes the importance of diversity and the necessity of writing diverse settings and characters; that’s not something I’ve seen mentioned often enough in writer’s guides not explicitly devoted to the topic. I also appreciated the attention given to narrative design, which is a tricky topic and often handled too cavalierly, and to the role of history, culture, and things like “consistent inconsistency” in setting. VanderMeer gives the reader a lot to think on in each chapter, never reducing the point to something simple or singular—something that makes Wonderbook perhaps a little challenging, at points, for a new writer. But challenging in the right ways.

The resources beyond the text, too, deserve a brief mention: WonderbookNow.com is referenced throughout the text as a source of writing exercises, further essays, and general extras. One of these, for example, is an editorial roundtable, where various editors of renown take on a short story to provide commentary. The use of the digital archive makes for an experience of text beyond the text, introducing yet further complexity and exploration—optional, of course, but there for the reader who’d like to know more about a given topic.

Overall, this was a fun book to read—but didn’t skimp on the information, or on delivering it in honest, multilayered, personal ways. The art is handsome, the diagrams are a delight, and the design serves a fantastic purpose: rendering the act of discussing writing even a touch as organic as the actual process. It’s a valuable endeavor, and I think that it will serve its audience well.

Wonderbook is available now from Abrams Image

Read an excerpt from the book here on Tor.com

Lee Mandelo is a writer, critic, and editor whose primary fields of interest are speculative fiction and queer literature, especially when the two coincide. She can be found on Twitter or her website.