One of my many roles in life is being the dad to a bright and creative three year old who loves story time. So, I read a lot (a looooooooot) of kids’ books each day. So, cracking open Greg Manchess’s Above the Timberline felt familiar, despite being unlike anything I’d ever read before. Like a kids’ book, you’re greeted with bold, engaging illustrations, and splashes of text that accentuate the visual storytelling.

Reading Above the Timberline feels at once like something unique—a vivid and whole rendition of a storyteller’s vision—while also bringing back waves of nostalgia as I remembered reading the same books my daughter now enjoys, and the way I would sink into the visual and literary creations of their authors.

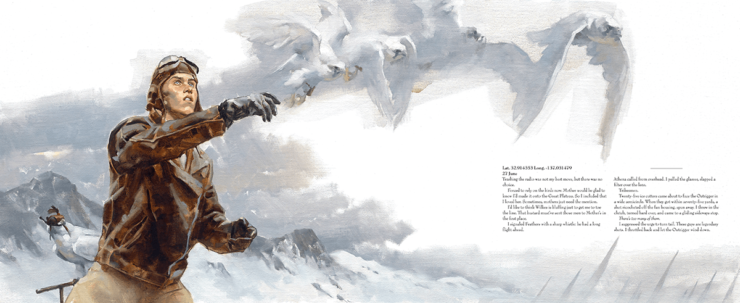

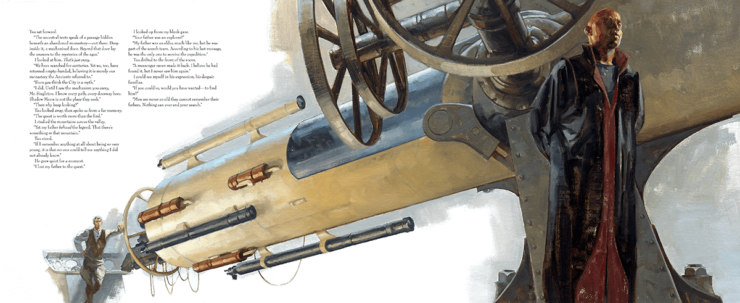

Immediately, you’re struck by the elegance and beauty of Manchess’s art. There’s a richness to it, a depth and history that seems to extend far beyond the pages. Manchess is deservedly considered a master of his craft, and to see his imaginative take on post-apocalyptic/ice age America rendered with such breadth is breathtaking. The book’s broad, expansive canvas—each double-page like a 16:9 theatre screen—allows room to breath, and Manchess makes use of the space to create dramatic tension similar to a comic book or graphic novel. It’s a compelling meeting of many storytelling mediums. While it’s a quick read, clocking in at about 240 pages, there is more to the experience than just skimming the text. Each page pulls you in and demands attention.

Buy the Book

Above the Timberline

Structurally, Above the Timberline is Disney-esque. There’s a lost city and a missing father, an obvious villain, and a naive young hero. Hell, there’re even animal companions. No singing, though. Like a good Disney flick, it establishes a quick pace and never lets up. Since Manchess’s art does so much of the heavy lifting—handling everything from worldbuilding, action, and even some of the more subtle aspects of dialogue, like body language—the accompanying prose is rugged and lean, reading almost like a film script. The prose might lack the sophistication and polish of Manchess’s gorgeous artwork, but it does a serviceable job of filling in the gaps and providing the story with its finer points.

Above the Timberline is set on a future version of Earth that was knocked from its axis by a major occurrence of tectonic movement. The result is a global ice age, and an American society that resembles that of early 20th century Britain—adventure and exploration abound, with a world full of mysteries just waiting to be discovered by those brave enough to seek them out. It’s a terrific take on an often tired post-apocalyptic genre, and rendered beautifully by Manchess’s art.

The book’s prose is presented to the reader as a mixture of radio transcripts, journal entries, and the more traditional narrative style that you’d expect in a novel. Fitting with the setting, the writing is clipped and rough around the edges, as though you’re actually reading someone’s unfiltered firsthand account. Whether this is the result of being Manchess’s debut as a prose writer, or an intentional stylistic choice, it works well—though sometimes it can be difficult to tell the voice of one character from the next.

Also owing to the book’s setting is its most vital flaw: women. Or, rather, lack thereof. Linea, who appears halfway through the book, is the only prominent female character (the other, the protagonist’s mother, appears briefly before being kidnapped by the bad guy), and though she’s interesting (far more so than the protagonist, to be honest), she is also the victim of many lazy tropes, including:

- She’s torn between her affection for the protagonist, whom she has just met, and her longtime (but potentially) loveless partner;

- She’s the object of a political feud between two men; and

- Her mother left one of the those men for the other, inciting the political feud.

Linea is strong and capable. She’s smart. And she would have been so much more interesting if all of her conflicts weren’t about warring men.

Beyond that, it’s slim. There are many, many people pictured in the illustrations—from explorers to mechanics, monks to hunters, and very rarely are they depicted as women. Were the explorer leagues of early 20th century Britain dominated by men? Likely. I don’t know for sure. But, Manchess could have done better when creating his own version of that society. This is a solvable problem, so, if Manchess chooses to return to this world, which I’d love to see, he can improve upon it. Fortunately, diverse ethnicities and cultures are well-represented throughout the story.

As someone who enjoys fiction predominantly through novels, books like Above the Timberline are terrific reminders that there are many storytelling mediums, each with their own strengths. Manchess combines his signature art with a compelling plot, making for an experience that’s almost impossible to put down. You want to know what happens next, but you need to see the next illustration.

Just. One. More. Page.

Above the Timberline is available from Saga Press.

Aidan Moher is the Hugo Award-winning founder of A Dribble of Ink, author of “On the Phone with Goblins” and “The Penelope Qingdom”, and a regular contributor to Tor.com and the Barnes & Noble SF&F Blog. Aidan lives on Vancouver Island with his wife and daughter, but you can most easily find him on Twitter @adribbleofink.