Notes from the Fog, the latest collection of stories by Ben Marcus, was initially announced as Speeding Pieces of Light. I think the final title is the more appropriate: light and fog are equally ungraspable, but Marcus proves fonder of shadows than of illumination. Readers and characters remain in the fog, and such beams of light that appear are precious indeed.

Ben Marcus is a writer who should be dear to my heart: in his twenty-odd years in American letters, he’s been a tireless advocate of fiction that is challenging or experimental, fabulist or fable-like, uncompromising and unnerving. He’s also a fine critic—his essay on Thomas Bernhard for Harper’s, for example, is wonderful—and he deserves a medal for the return to print of Jason Schwartz’s A German Picturesque, a book of sinisterly fluid babble forever hesitating on the border of perverse sense. All of this explains why I wish I could give Notes from the Fog an unqualified rave, and why I’m sad to write a thoroughly mixed review.

To begin with the bad news, some of the stories in Notes frustrate in their conventional unconventionality; Marcus sometimes sends multiple notes from the same coordinates in the fog. Take, for example, “Precious Precious,” with its talismanic symbols (a mysterious pill, “not for moods, she was told, but possibly for the lack of them”), its extended non-conversations communicating non-connection (“Sometimes even I don’t know what I do. They don’t always tell us what things are for.”), its dreary sex (“lifeless baby wiener”), and its concluding epiphany (“those shiny things in the grass”), which seems all too familiar. And some of his put-downs of vapid complacency fail. How likely is it that a character, having made apposite reference to an obscure book, will then explain “it’s like a fiction novel”?

Now that I’ve expressed these reservations, let me proceed to the good news: Marcus is a fine writer; readers who underline especially good sentences ought stock up on ink before beginning this collection. Tall grass resembles “Some original, beautiful creature that needed no limbs or head, because it had no enemies.” And, for all his reputation as a cerebral experimentalist, he’s also quite funny, with a penchant for wry asides and the occasional dirty joke. And while a few stories seem rote, others impress and perturb in equal measures.

“Cold Little Bird,” the first story in the collection, concerns a child who suddenly, and for no apparent reason, rejects his parents. There are, of course, innumerable precedents for tales of inhuman children—the distraught parents even discuss Doris Lessing’s The Fifth Child—but what makes the story so chilling is precisely what the boy doesn’t do. Aside from making one threat, he never does anything wicked; he doesn’t terrorize his brother or torment his babysitter; the neighborhood’s cats roam unmolested and no schoolmates plummet down stairs. It would be a relief if little Jonah showed himself a Bad Seed, but he never does.

“A Suicide of Trees,” by far my favorite story in the collection, concerns a vanished father, a disappeared lodger, a stymied detective, sinister day laborers. Marcus provides clues, innuendos, apparitions, and enigmas enough to populate several conventional mysteries, but the detached narration, vague characters and cryptic asides create a dreamlike atmosphere that precludes closure. A solution, of sorts, does arrive, but of course it only plunges us deeper into the dream. As the narrator says of one perhaps vital clue, “asleep or awake, I saw it very clearly.”

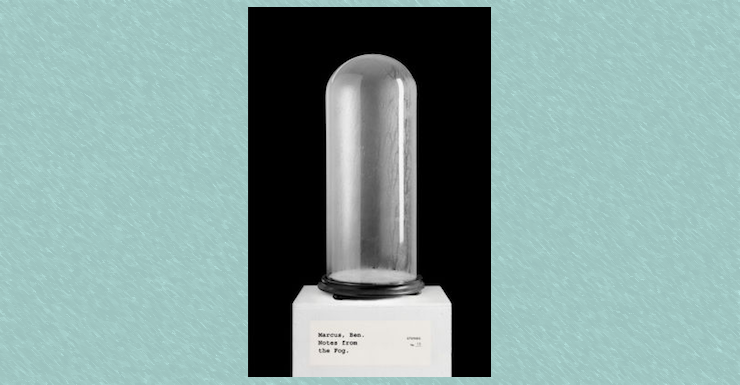

Buy the Book

Notes from the Fog: Stories

“Critique,” one of the shortest stories in the collection, with its complete lack of characters and its conflation of reality, art, and simulacra, reads like a violent collision between Beckett and Borges at MoMA, while “Blueprints for St. Louis” could be a violently compressed Don DeLillo novel, with perhaps the smallest taste of late-period J.G. Ballard.

Language, and its failures, is the collection’s dominant intellectual theme: after a sparing private vision, the deranged protagonist of “Omen” reflects that “there wasn’t really such a good word for how it all looked from up there where he was.” One of the depressed architects in “Blueprints for St. Louis” reflects that finding le mot juste may well be impossible: “It was the hardest thing in the world. There wouldn’t be language for this. Not in her lifetime.” And while the insufficiency of words may strike some readers as being too dry a theme, there’s a surprising emotional warmth to several of these Notes, particularly those dealing with parenting, its ambiguities, and its ambivalences. I suspect Marcus, had he wished, could have been a very good writer of conventional realism.

On balance, I enjoyed Notes from the Fog, for all its unevenness, this collection proves Marcus a compelling and original voice. It’s not the kind of book that will ever be popular, and I wouldn’t recommend it to most readers that I know, but for a few daring readers, an entry into this mist will be amply rewarded.

Notes from the Fog is available from Knopf Doubleday.

Matt Keeley reads too much and watches too many movies; he is helped in the former by his day job in the publishing industry. You can find him on Twitter at @mattkeeley.