“So, how do you feel about the ‘90s being back,” a friend asked me a few days ago, watching a teen dressed head-to-toe in velvet cross the street. To which I replied, “it’s nbd to me, baby. I kind of never left.”

Too-glib of an answer, maybe, for someone on the later side of being a millennial, but I was sporting spaghetti straps and a friendship bracelet that day, and the truth is, my loyalty to the ‘90s has genuinely never waned. Between the high-waisted mom jeans that I refused to give up for scene-kid skinnies, to the sullen disaffection that dominated my CD collection; sometimes, you just have to admit that the stuff you were saturated in as an adolescent did, in fact, leave an indelible stain on Your Whole Deal. Just no fighting it, for better or for worse.

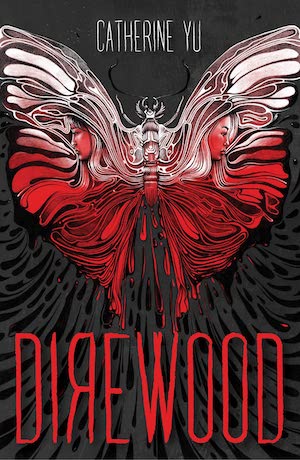

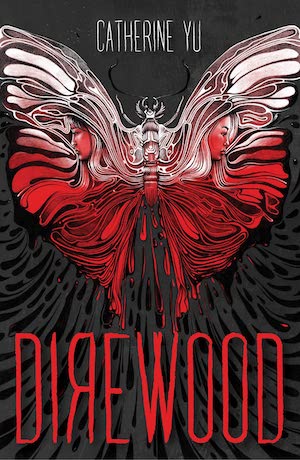

No surprise then, that when Direwood, Catherine Yu’s young adult debut and self-purported “velvet-clad 1990s gothic horror” showed up, featuring a charming vampire and a slew of teenage disappearances, I snapped instantly to attention.

Set in the pristine, suburban town of Glen Hills, Michigan, Aja is a sixteen-year-old who feels chronically underlooked by her peers and her mild-mannered dentist father. This sense of difference is only exacerbated by her perfect older sister, Fiona, who fits in easily with pastel babydoll dresses and neatly braided hair; who’s popular at school and excels at extracurricular Chinese class as well as in her volunteer work. In comparison, Aja pales. But everything changes just after Fiona’s seventeenth birthday, when she mysteriously disappears. Other kids follow. The whole neighborhood’s in denial that anything’s wrong, but the rain reddens and the elm trees are dying; their bark flaking and wormed through with parasites. When a vampire with dark eyes, Padraic, comes tapping at Aja’s window to invite her away, she’s certain that he’s the key to Fiona’s disappearance. Reluctantly, she cuts a deal, agreeing to go wherever Padraic takes her, so long as she’s allowed to return home within the first seven days. Beyond that, there’s only risk—and as to what the vampire truly wants with her, it’s difficult to know.

Buy the Book

Direwood

Given the dangerous game that Aja is playing, Direwood is filled with an elegant sort of dread, heightened by Yu’s sparse style. Each sentence strains with a palpable, propulsive tension. And yet, there’s something luxurious in how the details of the grotesque are fully indulged rather than shied away from. Bodies in this novel (whether human or caterpillar) are always squishing or leaking, their integrity threatened by intrusion or decay, while blood seeps from the protagonists’ wounds as excessively as it does from the sky. There are numerous flesh-eating insects. Yu builds intensities of atmosphere that often take precedence over plot, but the flip side of this is that she does succeed in producing some truly visceral moments that had me gnawing at my finger.

Spoilers follow

Although the driving force of the novel is the mystery of Fiona’s disappearance, its injured, bleeding heart is Aja’s overwhelming sense of inadequacy. An Asian American teen, slouchy and ill at ease within a predominant culture of whiteness, Aja balks against the assimilationist flawlessness that Fiona and her father strive for. Unlike them, she finds it difficult to tolerate the underhanded compliments from the neighbors that deem them as “good ones.” She can’t find it within herself to conform to their expectations, especially when she knows no matter how many pairs of khakis her family buys or picnics they host, they will always be treated as “outsiders.” Of course, despite her resistance to all of this, Aja, like any regular human, has a desperate, confusing desire to be loved. Yu excavates this classic teenage conundrum with great tenderness—would Aja be happier if she were effortlessly popular like Fiona, or would she prefer to be celebrated for uniqueness? She doesn’t quite know—which is why Padraic’s sweet blanket insistence that Aja is his ‘favorite’ has such allure.

Indeed, perhaps Direwood’s greatest strength is its deep dive into the damaging, but relatable logic of ‘specialness.’ After all, who doesn’t want a handsome stranger to show up and tell them they’re extraordinary, then whisk them clean away from the banality of their life? But Yu casts aspersions on the cost of exceptionalism, not just for Aja but for all her characters. Back at Padraic’s lair, an abandoned church within a layer of protective fog, we meet Kate, a younger vampire. Vicious, with a penchant for playing with her food, she’s enthralled two of Fiona’s friends, Hazel and Noah, who compete endlessly for the honor of being Kate’s favorite blood-source, oblivious to the fact that they might die in the process. Kate, in turn, is fated to watch her beloved Padraic search interminably for a ‘favorite’ amongst human girls, when he’s made clear that Kate will never be considered for that role. Not to mention, favoritism, ever-reliant on someone else’s whims, is fickle and turns on a dime. In a Bluebeard-esque twist, we learn that Aja is not the first ‘favorite’ that Padraic, lonely and listless, has brought back to his coven, and that previous holders of that title have not exactly been uh, well-fated. If there’s a true horror in Direwood, it’s the revelation that trying to make yourself perfect by anyone else’s standards will, quite literally, start eating away at your insides.

Yu does a nuanced job of illustrating the contradictions of Aja’s close interiority—her undoubted attraction to Padraic set against her loyalty to Fiona; her urge to return to normal life versus the seductive potential of letting herself explore what she really desires. But at times, the dynamics of Aja’s interpersonal relationships do feel a bit clunky. Aja’s best-friendship with Mary, for example, is a series of conflicts (as all best friendships should be), but we don’t quite get enough anecdotal detail or emotional scaffolding to reconcile the blood oath between the two girls and what’s bluntly stated as Mary’s white savior complex—even if Aja’s experience of her microaggressions feels well-rendered. Similarly, Aja’s relationship with Fiona doesn’t manage to transcend traditional sibling dynamics enough for the Ginger Snaps ending to have the same tortured resonance. And Aja’s fascination with Padraic, while initially compelling, starts to feel tedious as she continually wavers between seeing him as human or monster, stuck in the slippage between.

In the last chapter of the novel, just as things are getting smoothed over as freakish acts of nature, Aja makes a casual nod towards rumors in the neighborhood that the recent disappearances were in fact the workings of a ‘teenage death cult’—an adult paranoia just so frickin’ 90s that it hurt my teeth. And although Yu does a wonderful job of lending period-specific detail to her story—from Beanie Babies to scrunchies and copies of Sassy magazine—I was left feeling like Direwood was a missed opportunity to really delve into what made the 90s a uniquely contradictory time to be a teen—the spirit of creative agency that flourished within youth culture and the early internet, yet the suspicious backlash that this engendered in return.

“I wished everything was different,” Fiona confesses to Aja, right before she disappears, then “smiles and [Aja doesn’t] recognize her at all.” Ultimately, Yu has written a novel that forces us to interrogate what’s rotting under our illusions of wholesomeness or perfection. By playing with the narrative capability of bodily sensation, she slides easily between layers of horror and emotion—reading this novel often feels as if one is burrowing deeper and deeper into a wound. But what lies beneath is not always what’s painful or destructive. It can also be the truth. And as Direwood’s textures molt away, something new emerges—Aja herself—unrecognizable too. Unlike Fiona, perhaps she’s better for it.

Direwood is published by Page Street Kids.

Trisha Low is the author of The Compleat Purge (Kenning Editions, 2013) and Socialist Realism (Emily Books, 2019). She lives in the East Bay of California.