Screw Roland Barthes: if ever the identity of the author mattered to how a piece of literature is understood, it matters to Palestine +100.

The nationality of the authors in this collection is relevant for several reasons. First, because this book is (according to the publisher) the first ever anthology of Palestinian Science Fiction. But it matters also because this collection is an important statement on how Palestinian artists see themselves, and how they view their national prospects in the decades to come.

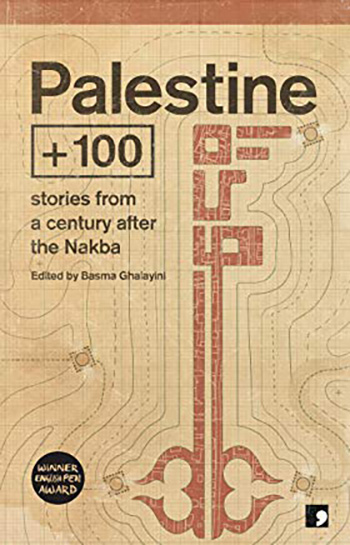

The premise of the book is a simple one. A dozen authors are invited to write a story set one hundred years after the establishment of the state of Israel in 1948. During the creation of that new country, more than 700,000 Palestinians were forced to flee their homes, an event that they and their descendants have come to know as the Nakba (‘catastrophe’). This was the event that created refugee camps all over the Levant, and in turn a sense of the Palestinian ‘right of return’ to the homes they left behind. This concept haunts every negotiation between Palestinian representatives and the Israeli government… and it looms large in this collection too.

As one might expect from a diverse set of contributors, the short stories each have their own styles, and each is an idiosyncratic slice of ‘what if?’ The centenary of 1948 is only twenty-nine years away, so officially these stories should be near futurism, a short extrapolation from the tech and obsessions of the 2010s. But really, each tale is simply about how things look immediately after a change… whatever that change might be. In some stories, that just means better surveillance drones for the Israeli Defence Force, or a ratcheting up of air pollution due to climate change. In other cases it means parallel worlds, time reversal, Matrix-level VR… or the arrival of actual aliens.

But whether the SF is mildly speculative or wildly fantastical, a sense of melancholy imbues each story… even the funny ones. And when we see the authors’ names and read their biographies at the back of the book, how can we not equate this resigned pessimism, with what it means to be a Palestinian in the twenty-first century?

To say that this book evokes negative emotions is not a criticism, and nor should it be a reason to avoid it. On the contrary: it’s the very reason why this book should be read widely. It would have been easier for these authors to conjure us a dozen utopias, fan service to the pro-Palestine movement, where technology has somehow cured the warring parties’ mutual fears, and everyone is liberated. But such stories could never convey the complexities of the situation in the way Palestine +100 manages to do. Such wish-fulfillment would not produce stories such as these, which linger and bother the reader, long after each concludes.

Some stories do skirt around the shores of escapism, though none embrace it fully. In ‘Application 39,’ Ahmed Masoud presents us with a collection of independent Palestinian city states, and the surprisingly successful bid of Gaza City to host the Olympic Games. The story centres around the two buoyant shitposters who submit the bid for LOLs… but their enthusiasm is not enough to offset the animosity not only of Israel, and not only of the surrounding Arab states, but of their neighbouring municipalities too. The distrust in the region is a fractal, still present however close to the ground you zoom in.

The distrust between Palestinians, and the role that plays in their political stasis, is set out in the heartbreaking story ‘Vengeance’ by Tasnim Abutabikh. It centres around a young man, Ahmed, who has ‘inherited’ an oath of revenge against another family. In a wonderfully realised version of Gaza that is being literally suffocated, he stalks and then confronts his target:

‘The landowner was your great-great-grandfather,’ Ahmed concluded. ‘The boy was my great-grandfather.’

Blood-debts that span generations, handed down like heirlooms from father to son – this is all the stuff of a high fantasy saga, yet versions of this story are playing out for real, right now, in the refugee camps of the West Bank.

The protagonists do not always take on the demands of their ancestors willingly. The compelling idea in Saleem Haddad’s ‘Song of the Birds’ is that it is the ‘oppressed’ mentality itself that is stunting Palestinians. ‘We’re just another generation imprisoned by our parents’ nostalgia’ says Ziad (himself a ghost inside his sister Aya’s dreams).

Haddad’s story opens the collection and is well-crafted, challenging and complex. The titular ‘song’ of the birds unlocks a shocking realisation about the version of Palestine that Aya inhabits, and the birds’ refrain (‘kereet-kereet’) plays a similar role to the poo-tee-weet of the birds in Kurt Vonnegut’a Slaughterhouse 5, calling and drawing the confused protagonist back and forth across the membrane of the parallel words (or are they consciousnesses?)

Ziad’s blasphemous notion that perhaps the Palestinians need to just Let It Go is present in other stories too. ‘The Association’ by Samir El-Yousef (tr. Raph Cormack) describes a peace process based on enforced forgetfulness, where the study of history is banned. The murder of an obscure historian leads an investigative journalist into a murky underworld, where the radicals are no longer taking up arms against an occupation, but simply reminding the people of inconvenient past. ‘To forget is a sin,’ says the mysterious doctor. ‘To forget is a sign of deep-rooted corruption.’

It is in lines such as these that the book’s authors seem to be in dialogue with each other. They ask, first, the extent to which their people must let go of their past in order to secure a future; and second, how much their past defines who they are.

Moreover: how much does the presence of the Israelis and their nation-building project impact on what it means to be Palestinian? Variations on this theme are present throughout the collection, in particular in ‘N’ by Madj Kayyal (tr. Thoraya El-Rayyes). Here, the solution to one of the world’s most intractable disputes is simple: fork the universe. Create parallel worlds (well actually, because they’re on a budget, it’s just the disputed territory that gets duplicated) and let people decide which universe they want to live in. Palestinians who want their historic homes back can have them. Just shift over into the parallel Palestine, and a homeland can be forged there, free of settlers and the imposition of a Jewish state. But why then, do many Palestinians choose to stay in the Israel-universe? Why does the narrator’s son, known only as N, flit between two versions of Haifa? What are those in the Palestine-universe missing?

Every story in Palestine +100 mentions the Israelis. Yet they are strangely distant. Usually, it is the state of Israel is presented as a character of sorts, operating its drones or maintaining a blockade. Rarely do we get under the skin of its Jewish citizens. But when they do appear as central characters, we get a strong sense of the Israeli fear of the Palestinians, and the role that plays in perpetuating the denial of full human rights. In ‘The Key’ by Anwar Hamed (tr. Andrew Leber) and the surreal ‘Curse of the Mud Ball Kid’ by Mazen Maarouf (tr. by Jonathan Wright), we see how the very presence of Palestinians can come to haunt and harass Israeli citizens. Neither story makes clear the true nature of the apparitions that appear to the Tel Aviv urbanites and the kibbutzim, but the message is clear: just as the Palestinians will never be able to return to pre-Nakba days, the Israelis will never be rid of the Palestinian presence around them.

‘Digital Nation’ by Emad El-Din Aysha is also told from the Israeli point of view. Asa Shomer is director of Shabak, the internal security service, and he is tasked with catching a set of hackers who infuse Arabic into the all computer systems.

That virus was a stroke of genius, Shomer had to admit. Who needed to ‘liberate’ Palestine of you could convert Israel into Palestine?

The director sees this intervention as a terrorist’s virus. But the perpetrators are more multicultural than he supposes, and the outcome far more positive than he can imagine. For this reader, the overlay of Arab culture onto the Israeli project, was the part of the book I found most uplifting.

“History is not one thing,” says a character in Lavie Tidhar’s Unholy Land. “It is a tapestry, like an old Persian rug, multiple strands of stories criss-crossing.” I thought of that metaphor often while reading Palestine +100. Every story in this collection has two or three themes tightly knitted together. This book is not a happy read, but it one that complicates our worldview, undermines our certainty and unravels our righteousness. We need more literature like this.

Palestine +100 is available from Comma Press.

Robert Sharp is a free speech activist and former head of campaigns at the English centre of Pen International. His novella The Good Shabti was nominated for the Shirley Jackson Award. Find him on Twitter @robertsharp59

Oh man, instantly intrigued, thanks!

Ziad’s blasphemous notion that perhaps the Palestinians need to just Let It Go is present in other stories too. ‘The Association’ by Samir El-Yousef (tr. Raph Cormack) describes a peace process based on enforced forgetfulness

See Greg Bear’s near-future thriller Quantico, about a group planning to use a bioweapon on religious sites in Rome, Jerusalem and Mecca which will induce loss of memory.

As much as I am happy as a sf reader about this stories as an Israeli I’m deeply sad. It seems that even in the sf landscape a valid peace is not an option. However sf is all about optimism, so maybe those stories (and others) would help to make a change.

Thanks for the comment, NF. I’d love to know what you and other Israelis think of the collection, just as I’d like to read the reactions from other Palestinians.

I’m not sure I agree that “sf is all about optimism” – sometimes, surely, it can be pessimistic extrapolation. Though that’s not to say that pessimistic story cannot bring about positive change, which is what I hope this book and literature from the area (Israelis of all ethnicities and religions, Palestinians living in Israel, Gaza, the West Bank or in exile) can bring about.

As an Arab and muslim with many Palestinian friends, whose heart has ached for them, it makes me glad to know this book even exists. I look forward to reading and learning from it.