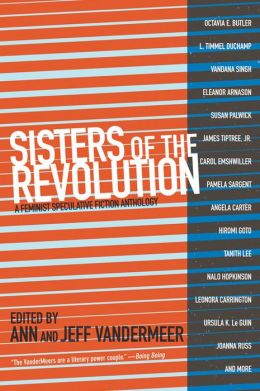

The stories in Sisters of the Revolution: A Feminist Speculative Fiction Anthology does exactly what you’d want them to—they tear apart cliches, they question gender and it’s implications, they look at identity using satire and humour and darkness with a sharp intellectual examination of stigma and society’s rules.

Put together by well known and highly regarded award winning editors Ann and Jeff VanderMeer, it’s a solid collection for anyone who wants to see how far feminist SF has come, with stories spread across the last 40 years or so.

Sisters of the Revolution began life as a Kickstarter campaign and is co-published with PM Press. The stories are from a wide variety of SF-nal genres—there’s futuristic SF, there’s fantasy and myth and surrealism. While the stories are mostly reprints, they’re each an equally strong voice, placing classic SF writers like Ursula Le Guin and Octavia Butler along side contemporaries like Nalo Hopkinson, Nnedi Okorafor, Catherynne Valente and Karin Tidbeck. Though the classic are of course, always wonderful to read and admire (who isn’t still affected by James Tipree’s The Screwfly Solution, even at a repeated reading?), it is of course some of the newer stories that have not been read before that may stand out more, especially the ones that bring to attention writers of colour from non-western cultures. Nnedi Okorafor’s strong oral storytelling style in The Palm Tree Bandit is perfect for the tale of the woman who upends patriarchal norms and help change society. Nalo Hopkinson’s wonderful rhythms in the story The Glass Bottle Trick create an effective, chilling atmosphere for her take on the Bluebeard myth. Hiromi Goti’s Tales from the Breast is a beautiful, evocative story about new parenthood, nursing, and the complicated relationship between a new mother, her body, and her baby.

Some of the other contemporary stories that stand out are Catherynne Valente’s Thirteen Ways of Looking at Space/Time, a Locus Award finalist in 2011 and a reimagining of the creation myth; Ukrainian writer Rose Lemberg’s Seven Losses of na Re, about a young woman whose name is power; and Swedish writer Karin Tidbeck’s Aunts, a fantastic story about three enormous women who only live to expand in size. They eat and eat and eat, until they are so large that they can not breathe. They then lay down and die, with their bodies split open for their awaiting nieces to dig out the new ‘aunts’ from old ones’ rib cages.

The collection includes writers whose stories are now synonymous with SF in general (not just feminist SF): Ursula Le Guin’s Sur is about an all female team of explorers headed to Antarctica, Octavia Butler’s The Evening and the Morning and the Night is about a gruesome, horrific fictional disease and the equally horrific societal stigmas that result from it, Joanna Russ, whose seminal 1975 novel The Female Man had a massive impact on many women writers is featured in the anthology with a forty year old story called When It Changed, one that remains valid to this day, in its look at power dynamics between the sexes.

Tanith Lee’s inclusion in the anthology now feels poignant, given her recent death, but there is even more reason for more people to read her work and note her significance. This collection includes her 1979 story Northern Chess, a cleverly subversive sword and sorcery tale featuring something rare in such stories from that time—a female lead with agency and power.

Another name that deserves mention is of course Angela Carter, whose influence is vast. Her take on Lizzie Borden’s story in The Fall River Axe Murders is about the woman who hacked her family to death yet was eventually acquitted. The entire story takes place in moments (though it’s over a dozen pages long) and leads up to what we already know—that Lizzie would brutally murder her family. But it’s unimportant that we already know where this is headed—this is Angela Carter, even her weakest stories (if there are any) are masterpieces of mood and atmosphere. Of course, in this story Carter is very much pointing out that the damage done to a young woman by not allowing her to grow, to learn and to be free is irreparable, and affects more than just the woman in question.

In the introduction to Sisters of the Revolution, the editors accept that a collection like this will always seem a little incomplete, always seem a little lacking, given that the canon of feminist SF is constantly increasing—particularly when it comes to including more POC female writers, more and more of whom are finding their voices, finding their groove, their space in the field. Regardless, a collection like this holds its own firmly and is a great resource for anyone looking to understand the history of feminist SF short stories.

Sisters of the Revolution is available June 1st from PM Press.

Mahvesh loves dystopian fiction & appropriately lives in Karachi, Pakistan. She writes about stories & interviews writers the Tor.com podcast Midnight in Karachi when not wasting much too much time on Twitter.