Though it would be wise to question this quote, it was Sir Arthur C. Clarke who supposedly wrote that whether we are alone in the universe, or we are not, either possibility is equally terrifying. That’s as may be for many, but not so much for Penelope Crane, the young woman at the heart of Spare and Found Parts. I suspect she would be happier to see aliens invade than spend another second feeling like the loneliest girl in the world.

To be clear, Penelope—Nell to her nearest and dearest—has people. She has a friend, a father, and a fancy-man. But Ruby Underwood is increasingly nervous around Nell; Julian Crane is too busy making amazing machines in his basement to take the slightest interest in his disconsolate daughter; and Nell has never felt anything other than resentment for Oliver Kelly, who’s so popular he makes her appear a pariah by comparison.

Nell’s unpopularity among her peers is not the only thing that sets her apart, sadly. Among the population of the Pale, “it was commonplace to sport an arm, a leg, a set of ears, two fingers, or even the bottom half of a jaw crafted from exquisite, intuitive prosthetic. Absent limbs were part of the price the people of Black Water City paid for surviving the cruel touch of the epidemic. Nell, however, was the only person with all her metal inside. She was the only person who ticked.”

The fact of the matter is that she’s only alive thanks to her mad scientist father. But the clockwork contraption she has instead of a heart has made the life she’s lucky to have hard. It’s made connecting with anyone a catastrophe waiting to happen:

The fact of the matter is that she’s only alive thanks to her mad scientist father. But the clockwork contraption she has instead of a heart has made the life she’s lucky to have hard. It’s made connecting with anyone a catastrophe waiting to happen:

Any time Nell thought about boys, or girls for that matter, she immediately sabotaged her fantasy self out of any romance. No beautiful strangers waited in the lamplight to whisk her away from her life, and if there were, Nell was certain that she’d viciously alienate them in less than five minutes flat. If it weren’t her dour expression or the scar that ran from her chin to her gut, then the ticking would send them running. There’s not much thrill in kissing a grandfather clock in a girl’s dress. Nobody wants to dance with a time bomb.

Nobody wants to hold one’s hand, either, just as nobody has ever held Nell’s. And so: she’s lonely. Lonely enough, I’d go so far as to say, to prefer the apocalyptic appearance of intelligent life forms from beyond to her own pitiable prospects.

I should probably point out that there are no actual aliens in this novel, nor indeed invasions, but after salvaging a mannequin’s hand while beach-combing for bits and bobs, Nell hatches a plan that’s apropos—a plan to create a kind of life that’s within spitting distance of Clarke’s terrifying extra-terrestrials: the precise kind of life that caused the aforementioned epidemic that lay waste to this world. In short, Nell is going to build a robotic boy to hold her hand because she doesn’t believe anyone else will:

If it were possible to build parts of a person, it was possible to build a whole one. Of course it was. If people were afraid of coded magic in steel boxes, she’d take the magic out of the steel boxes and put it in a brand-new body. Not a stone giant. One just her size. A whole person. Hang limbs on a spin and find a way to give him a brain, a heart—a soul. Could you make a soul out of spare and found parts? Why not?

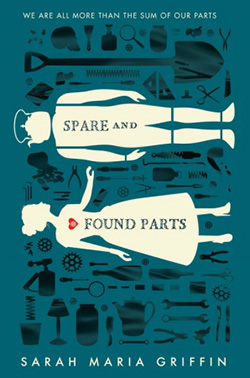

Buy the Book

Spare and Found Parts

Why not is what the remainder of Sarah Maria Griffin’s moving debut dances around, and it does so with such subtlety and sensitivity that readers are sure to sympathise with Nell even as her character develops from diffident to dangerous. At the start of Spare and Found Parts, her situation is a sorrowful one to say the least, and so resonantly rendered that of course we wish for her to find a way forward. But the scheme of her dreams isn’t just unorthodox, it’s potentially devastating. If androids like the one she’s designing in her mind brought about the end of the world once, what’s to say they won’t spoil it all a second time?

That we want what’s best for Nell, even if it means everyone else in the Pale—not to speak of the “healed” people of the Pasture who live in the relatively lush lands beyond its border—pays the price, says a great deal about the power of her primary perspective, and in turn Griffin’s ability to confidently steer her reader. Absent that last, there are things about this book that would prove markedly more problematic than they do: the wishy-washy worldbuilding, for instance; and the half-twists and quarter-turns that are transparent from the first; and the contrivances that too much of Spare and Found Parts’ meandering narrative relies on. Yet we become so invested in Nell and in her single-minded mission that because she overlooks these issues, so too can we.

I can’t give the ending such a pass, alas. It’s… deeply disappointing. I have no problem with last acts paced like races, nor conclusions that offer incomplete closure, but Spare and Found Parts’ final section feels like fiction on fast forward, and although it resolves the arcs of its characters, at a point the plot simply stops. Another chapter is all the novel really needs, but no: its author is evidently of another mind. Griffin doesn’t just leave the door open a crack to inveigle our imaginations, she heaves the whole thing off its hinges and tosses it, wall and all, into the middle distance.

As frustrating as the finale is, Spare and Found Parts is by and large a beautiful book, beautifully written, about beautiful things like love and life. It asks all the right questions, and it asks them earnestly; it just doesn’t answer them, or even try to, truly.

Spare and Found Parts is available from Greenwillow Books in the US and from Titan Books in the UK.

Niall Alexander is an extra-curricular English teacher who reads and writes about all things weird and wonderful for The Speculative Scotsman, Strange Horizons, and Tor.com. He lives with about a bazillion books, his better half and a certain sleekit wee beastie in the central belt of bonnie Scotland.