Krishna is quite unsettled when he bumps into a woman’s corpse during his morning bath in Kolkata’s Hooghly River, yet declines to do anything about it–after all, why should he take responsibility for a stranger? But when the dead start coming back to life en masse, he rethinks his position and the debate around how to treat these newly risen corpses gets a lot more complicated. In this story from Indrapramit Das, a journalist strives to understand Krishna’s actions and what they say about the rest of society and how we treat our dead.

1. Breaking Water

At first, Krishna thought the corpse was Ma Durga herself. A face beneath sun-speckled ripples—to his eyes a drowned idol, paint flaking away and clay flesh dissolving. But it was nothing so sacred as a discarded goddess. The surface broke to reveal skin that was not painted on, long soggy hair that had caught the detritus of the river like a fisherman’s net. Krishna had seen his mother’s dead body and his father’s, but this one still startled him.

Krishna dragged the body from the shallows to the damp mud of the bank, shaking off the shivers. He covered her pickled body with his lungi, draping it over her face. He returned to the winter-chilled waters of the Hooghly naked and finished his bath. The sun emerged over the rooftops of Kolkata, a peeled orange behind the smoky veil of monoxides, its twin crawling over the river. Morning reflections warmed the tarnished turrets of Howrah Bridge in the distance, glistening off the sluggish stream of early traffic crossing it.

Other bathers came and went, only glancing at the body. When Krishna returned to the bank, a Tantric priest was crouched over the dead woman. The priest, smeared white as a ghost with ash paste, looked up at Krishna.

“Is this your wife?” the priest asked.

“No,” said Krishna. “I don’t have one.”

“Then maybe you should be her husband.”

“What’re you on about?” Krishna snapped.

“She needs someone, even in death.”

“Maybe she already has a husband.”

“If she does, he probably argued with her, then beat her dead, maybe raped her while doing that, and tossed her in the river. Shakti and Shiva, female and male, should be at play in the universe. One should not weaken the other. This woman has been abandoned by man,” said the priest, gently touching the dark bruises on her face, throat and chest. Krishna thought about this. The priest waited.

“Fine. I’ll take her to the ghat and see her cremated,” said Krishna.

The priest nodded placidly. “You will make a good husband one day,” he said.

“Your faith in strangers is foolish,” muttered Krishna. Not to mention his sense of investigative protocol, Krishna didn’t say. The priest smiled, accepting this rebuke and walking away. Krishna didn’t know much about how washed-up, likely murder victims were handled, but he was sure just cremating them without a thought wasn’t how it usually went.

Still.

Krishna looked at the corpse. If he left her, someone would eventually call the police, and they would take her to a refrigerated morgue where her frightened soul would freeze. Her killer would remain free, the case unsolved, because since when did anyone really care about random women tossed into rivers? He thought of his mother cooking silently by lantern light, her face swollen.

He remembered asking a policeman on the street to take his father to jail for hitting his mother. He was laughed at. He remembered playing cricket on the street with the other slum boys, doing nothing to stop the beatings, waiting years until his father’s penchant for cigarettes and moonshine ended them instead. Not that it mattered, since his mother faithfully followed him not long after.

“Why don’t you take her to the ghat, you self-righteous bastard? You’re as much a man as me,” Krishna said aloud, looking at the priest, who was sitting quietly by the water. He was too far away to hear Krishna, not that Krishna cared. He shook his fist at the priest for good measure, then he peeled his lungi off the body, leaving the woman naked again. Sullen, he threw the lungi in his bucket and tied another around his waist. He always brought an extra in case he lost one in the water. He kissed his fingertips and touched them to the body’s clammy forehead, nervously keeping them away from her parted blue lips. For five minutes he sat next to her, as if in prayer, wondering how he might take her to the cremation ghats. Did the priest expect him to call a hearse, pretend to be a husband, and have her driven there? He shook his head and thought some more.

The priest had disappeared, but Krishna stayed there and thought and thought. Then he shook his head, got up, picked up his bucket and walked away. The sun had risen higher, and the crowds were beginning to gather like flies by the golden water. They looked at the woman lying there on the bank, but, blinded by her nakedness, by the ugly bruises that painted it, they all looked away and went about their day. They ignored her until the moment she got up and started walking across the shore, clumsy but sure, water-wrinkled soles sinking into the trail of footsteps Krishna had left in the mud.

Even then, they didn’t look for long, save for one man, who cried out in surprise from afar. An unsurprising reaction, since he’d just seen what he had presumed to be a dead body crawl a few paces, stand up and totter across the mud like a drunk madwoman. But no one else reacted, and he refused to let people think that he too was mad, so he pretended his cry was a prelude to his singing while he bathed, and tried to ignore the sight of the naked woman. Some others left the ghat in haste. The rest of the men took the first observer’s cue, looking away from the woman on the shore as they bathed, just as they would look away from a beggar with stumps for limbs hobbling across the ghat. She had gotten up, so she couldn’t be dead. Simple as that. Whatever her problem, naked women didn’t belong here, where men bathed, parading their lack of shame.

In the morning air, flies clothed the woman. Hesitant crows perched on her shoulders and head forming a feathered black headdress, bristling with flutter. She gave no regard to her beaked guests nor their violence as they haltingly pecked at her flesh, somewhat confused by her movements, but not enough to keep from tasting her ripe deadness.

The spectators stole quick glances at the woman while studiously ignoring her, horrified. This was a very mad woman. Undoubtedly sex-crazed, too, judging from her lack of modesty. Probably drunk. Crazy, for sure. And a junkie, and homeless, and a prostitute. So filthy that the birds were pecking at her. So high, she couldn’t feel the pain. Surely someone would call the police.

Carrying her hungry crows unwitting, she staggered on down Babu Ghat, wandering by the slimy stone steps that led to the rest of the city, as if unsure of how to climb them. She eventually found the garbage dump down the ghat and started eating from it.

Next morning, when Krishna heard that the dead were waking up all over the city—maybe even the state—his first thought was of the dead woman he had left behind on the ghat. He was at a paan shop on Gariahat, near the apartment building where he cooked meals for a few middle-class families in their posh homes, in their fancy kitchens with ventilation fans and shining tiles and big fridges. He was idly spitting betel juice at the footpath when the paanwallah mentioned history happening elsewhere in the city, pointing to a tiny television on top of his little Coke storage fridge.

The paanwallah seemed bemused by the news on the TV, not quite believing it. “No wonder traffic’s hell today,” he muttered, scratching his whitening moustache. “All morning, this honking, I’m going deaf.” He waved at the street and its cacophony of cars, buses, lorries and auto rickshaws stuck bumper-to-bumper like so many dogs sniffing each other’s exhaust pipes.

Krishna believed the news instantly. It couldn’t be coincidence that he’d discovered a corpse during his morning bath the week corpses started getting up and walking.

His second thought—accompanied by a bit of guilt for it not being the first—was of his mother; then, with some measure of fear, his father. But his parents were cremated and gone, safe from this mass resurrection, unless ash itself was stirring into life to fill the wind with dark ghosts. He also had to look up at the sky to make sure there were no clouds of ashen ghosts raging across it. Thankfully, there was only sunlight suspended in winter smog, pecked with the black flecks of crows.

The realization that his parents couldn’t return came as a relief to Krishna, since he didn’t know exactly how he’d have dealt with such a thing, especially after they’d been gone for two decades. The surge of elation and dread that rose from that thought filled his chest so powerfully that he had to steady himself against the counter of the paan stall.

Then he thought, I have to find the woman. That his parents couldn’t possibly come back to life only bolstered this thought. Surely his employers wouldn’t hold it against him if he missed a day, under the circumstances. In fact, Krishna suspected they’d be more preoccupied than most by this turn of events. He suspected that nobody living in those apartments really believed in God, despite their indoor shrines, and what better evidence of Bhagavan than this? It would throw them into confusion. Money and work be damned. For a day, at least.

“I found a dead woman. I left her; I have to find her,” Krishna said to the paanwallah, who was fiddling with his paan leaves, as if proud of their very appetizing green. Then Krishna ran off. “Hai-oh, that fellow’s looking in the wrong places for a wife,” the paanwallah mumbled.

As Krishna bussed across the city and back toward Babu Ghat, he saw the world as it always was but now a different place. The air you breathed felt different when you knew the dead walked around you. The traffic was even worse off than usual because of the confusion. The police were everywhere, their white uniforms ubiquitous among the crowds on the streets. Krishna heard snatches of conversations in different languages, all talking about the same thing. As sunlight shuttered across the smeared minibus windows, Krishna held his breath against the stink of sweaty passengers pushing up against him and listened. He heard wealthy students and youngsters babble incomprehensible English with unholy excitement, repeating one word, “zambi,” which was clearly what they were calling the risen dead. Krishna heard how bodies were rising out of the Hooghly and shambling in diverse but slow-moving crowds across the ghats of Kolkata. How they were falling—half-eaten by birds—from the Parsi Towers of Silence like suicides jumping to their new lives. How the Muslim, Christian and Jewish cemeteries were filled with the faint thumps and groans of the trapped dead, too weak to escape caskets and heavy packed earth. How medical schools and hospitals and police morgues were now dormitories for live cadavers kicking in their steel chambers. How these places were reporting the highest number of corpse-bites in the whole city because of staff convincing themselves that the chilled bodies they were freeing were poor souls mistaken for dead and frozen to drooling stupidity. He felt like he was having a panic attack, so filled was his head with this confusion of voices.

By the time Krishna got back to Babu Ghat early in the evening, the riverside was packed, like it had been during the immersion of idols after pujas. A column of crows towered above the ghat. The birds wheeled over the parade of the dead, taking turns swooping down and pecking at them. The police were keeping the walking corpses within the ghat by tossing lit (and technically illegal) crackers near their soggy feet every time they tried to wander up the steps. That seemed to do the job, sending the dead staggering back towards the water, though never back inside. Strings of bright red crackers hung from police belts like candy. Some of them held riot shields. In their hands were lathis that they swung in panic if the dead came near their barricade of live bodies. Their hatred for these creatures, these once-humans, was immediate and visceral. After all, every walking corpse on that ghat was a remnant of crimes they’d never solved or missing persons they never found.

Krishna witnessed the resurrection with nauseous excitement.

The Hooghly had disgorged the dead as if they were its children, all wrestling into the sunlight from a giant, polluted birth canal. They shone like infants fresh from the womb, swollen not with fat but water and gas. All stripped naked as the day they were born by water and time. Fifteen, twenty? Could they swim? Had they simply walked on the river’s bottom till they came upon this bank, all the while breathing water through their now-amphibious mouths? He was shocked that there had been that many unknown people lying murdered, drowned or mistakenly killed at the bottom of the Hooghly.

Some were only days old, looking almost alive but for their slack faces like melting clay masks, their lethal wounds and bruises, their paled and discoloured skin, their jellied eyes and the sometimes lovely frills of clinging white crustaceans in their hair, the tiny flickers of fish leaping from their muddy mouths. Others were black and blue, bloated into terrifying caricatures of their living counterparts, who watched in droves from behind the lines of fearful policemen at the top of the ghat steps. Fresh or old, all these dead men and women wading back to the world were united by the ignominy of their ends, un-cremated and tossed into the tea-brown waters of the Hooghly to be forgotten. Most, Krishna noticed, were women. All had crows as their punishing familiars, which clung to shoulders and heads as they tore flesh away with their beaks.

Krishna searched for a familiar face amongst the dead. He felt uneasy, not at the sight of the resurrected dead but at the roiling crowd he had to push through to witness this miracle, the street dogs biting and barking amid them to try and get to the corpses, only to be beaten back by the police. Some people lowed like animals, spoke in tongues or pretended to, blabbered prophecy; priests and sadhus and charlatans chanting to eager flocks of potential followers, many calling for the immediate destruction of these men and women who had been reincarnated into their own bodies—a sign, surely, that they were evil, condemned to rebirth as creatures even lower than the lowest of animals because of some terrible karmic debt. It made Krishna uneasy, scared, even angry. Clearly, these people rising from the waters had been wronged, had suffered the injustice of the earthly world, not caused them.

It was a miracle, Krishna told himself. It had to be.

Why, then, did this feel like the end of the world, with the police in their cricket pads and riot shields, the crowds coagulating into a mob, these terribly wronged souls blessed with new life being herded like cursed cattle?

The loud braying of horns and the glare of headlights swept across the crowd as two police vans with grills on their windows ploughed slowly through the crowd, nudging the spectators aside. Men in toxic yellow hazard suits got out. They held long poles with metal clamps, which Krishna had often seen dogcatchers use to grab strays off the streets. They were going to shove the resurrected into vans and drive them away, quarantine them somewhere. And then what? They could do anything to them: destroy them, imprison them. If the world knew about them from the news, they probably wouldn’t burn them, however much these policemen might want that. But if they took them away, they would be subject to any and all injustices that scared people could dream up.

As he was thinking this through, Krishna’s eyes caught the woman he had found yesterday. She was right there on the ghat. She was a little worse for wear, having spent a day doing whatever she’d been doing. But she was here and still . . . well, alive, he supposed. Walking with her resurrected sisters and brothers. Clearly, she had gotten away with being dead and walking around before the rest emerged from the water, perhaps because she’d looked somewhat alive when she washed up. No different from any wretched, broken beggar wallowing in garbage, to the average bystander.

The catchers made it through the crowd and neared the dead. Their plastic visors smudged them into faceless troopers, their poles spears shoved ahead of them, parting the howling people of Kolkata.

“Oh, god,” Krishna whispered, pushed from side to side by other sweaty shoulders. “God, thank you. I’m sorry I left her. I won’t again. I won’t.”

He shoved and struggled through the crowd, and shouted as loud as he could from behind the line of police. “My wife!”

Several policemen turned their heads and forced him back into the churn of people. He rebounded off the mob, back onto the officers. “I see my wife! Let me through!” he cried out.

They didn’t, but he pushed under their reeking armpits and broke through the line. He felt the sticks lash his back, bruise his shoulder blades, explode over his skin like crackers at the feet of the dead.

My wife. He heard himself. A decision made.

He ran down the crumbling ghat steps, stumbling as the sun sank and sloshed into the waters of the Hooghly. The baying of street dogs and the horns of a million cars stuck on the roads of B.B.D. Bagh rose into the evening, a trumpet sounding the end of an age.

And there she was, her long black hair threaded with garbage, crows on her shoulders. She looked at Krishna. Was there recognition in her eyes? No, she hadn’t even awoken to new life when he found her. And yet. For a moment, Krishna hesitated as all the corpses turned their numb gaze upon him, and the cloud of flies surrounding them surged against him, biting like windblown debris. But his fear of the police behind him was far stronger than his fear of the unknown. They would not follow him into this hell, so he ran forward, not back, his feet sliding on the filthy mud. He ran straight into the outreached arms and lizard-pale eyes of the resurrected, towards the woman who was to be his wife.

They embraced him as if he was one of their own, the flies crawling all over him as if they too had agreed to mark him as dead. Most importantly, she embraced him, peeling back her cold, heavy lips to bare teeth that still clung to purple gums.

2. Notes on Infancy

I first met Guru Yama when he was taking refuge with his “first wife” at the Kalighat Temple. This was just days after the resurrections became public, and just as it was becoming clear that they might be global, with cadavers reported to be rising up in countries all around the world, including our neighbours Pakistan, China, Bangladesh and Myanmar.

The guru was sitting in the courtyard where goats are sacrificed to Kali. They had closed off the altars from the public, and people were being allowed in one at a time to see him. No cameras. At that point, “Guru Yama” was just a nickname given to him by the news media, but it had caught very quickly. The corpse he’d claimed at Babu Ghat squatted near him. He’d publicly refused, over and over, to hand the cadaver over to the police or any other organization, claiming that it was his wife.

He seemed utterly stunned by the world when I saw him, clinging to the frayed rope tied around the purple neck of his wife as if it were a lifeline. Pierced into the skin of his other arm was an actual lifeline: an IV antibiotic drip on rubber wheels. Twenty-nine people around India had reportedly died from corpse bites left untreated. Each of the bite victims had also consequently become undead. The guru had been bitten but was given rabies and tetanus shots right after. He was younger than I’d expected, maybe even my age—mid-thirties at the most.

Covered in sweat, bandages over the bites his wife and the other corpses had given him, shivering with fever, eyes bloodshot, the guru told me both his life story and the story of his dead wife with stunning candour. For one thing, I didn’t expect him to confess that she wasn’t really his wife, or hadn’t been when he found her. The priests at the temple had conducted an impromptu ceremony after he arrived, though no one was willing to say what that meant. Most temples in the city, the guru said, wouldn’t let them in, declaring the risen dead abominations. He was lucky Kalighat Temple had offered to house him and his wife, as he couldn’t keep her in the basti where he lived. He told me how grateful he was for their help, and also thanked the lorry driver who had transported him and his wife from temple to temple, trailed by crowds looking for something to focus on in this bewildering time.

Though there were no laws in place for the risen dead, the guru considered himself legally bound to the woman he held by a rope leash, who had been dead for at least a week now. Because of that very lack of laws addressing this new world, the police or government couldn’t really dispute his claim, and they had other things to worry about right now, anyway.

Throughout the interview, I watched the guru’s wife with barely suppressed horror as she ate out of the opened rib cage of a goat that had been sacrificed, not for Ma Kali but for her. Or perhaps for both of them. The guru noticed the look on my face.

“She is a woman, just like you,” he said, which made me very uncomfortable. “Don’t be scared of her. You know what it’s like in this world. She asks only for sympathy.”

I tried to hide my unease. The corpse was squatting, much like her human companion, and using her swollen hands and darkening teeth to eat the entrails. It hurt to see the infantile clumsiness of those slowly bloating fingers. I was ready to run, but she never approached or even noticed me. She looked very blue-green, very inhuman, different from what she’d been in the footage from the ghat, embracing and then biting this man who called himself her husband. She looked—as much as I hated to apply that term to a real person who had lived and died—like a zombie. The people outside the temple had told me to wear a surgical mask and rub Vicks VapoRub under my nostrils (and readily sold me both on the spot), but I could still smell her, see the flies around her and the maggots in her nostrils and eyes and mouth.

“It’s good that it’s winter, no? She’d probably be falling apart by now if it were summer,” the guru said, looking at her. He stifled a shudder, wiping cold sweat from his brow. “We also have to make sure the street dogs don’t eat her. Usually, the dogs come in here when the goats are sacrificed, to lick up the blood. Not now, not now; we keep them out. They’d rip her up in minutes. Birds, also—they’re always trying. But humans are the worst.” He shook his head.

“She can’t protect herself anymore. All of these waking dead have been raped, beaten, strangled, stabbed, killed, thrown away. They deserve someone to help them, to take care of them in this new life they’ve been given by God. I’ve told all the news people, and I’ll tell you, that I’ll take care of them if no one else will. Everyone’s calling me Guru for that,” he laughed, eyes wide. “Guru Yama, they’re calling me. I don’t know about that. I don’t want to take the name of a god. I’m just a man.”

“But your parents already gave you the name of a god, Krishna. Is this different?” I asked him.

He seemed startled by this, and I felt bad for bringing up his dead parents. To my relief, he changed the subject.

“It doesn’t matter what they call me, I suppose. What matters is, I’m not afraid of these dead people. When I find somewhere to keep them, I’ll make sure they’re alright. When I am better, I’ll go looking for more before the police take them away and punish them again. Tell everyone. Bring me your dead, and I’ll care for them,” the guru said to me. From the fervent darting of his eyes, I couldn’t tell if he was a charlatan, if he was just looking for fame or up to something more sinister. I didn’t shake his hand, but I did smile at him, maybe in encouragement. I wondered about the rest of those dead people he had left behind at Babu Ghat, later taken away in those vans. It wasn’t the guru’s fault; how many dead could he walk around with?

Before leaving, I asked if I could use what he’d told me to write a story or an article. He gave me his blessing. I left to let his next visitor, whether journalist or would-be follower, see him. I managed to wait till I was out on the streets before vomiting, just a little, into a gutter. I’m not sure anyone in the crowd gathered around the temple even noticed.

I wrote in the midst of a global paradigm shift. I wanted to try and understand one man at that moment, as opposed to the impossibility of an entire world made new. Like anyone and everyone who would fixate on him in the days to come.

It was only afterwards that I thought to look for the identity of that poor dead woman by his side.

3. Notes on Maturation

The second time I saw Guru Yama, it was to identify his wife and return her to her mother.

I met the widowed mother, who requested I not include her name, at the Barista on Lansdowne. I bought her a plain coffee. As I handed her the cup, I marvelled at the fact that we can still enjoy the privilege of overpriced lattes and mochas while black government vans roam the state for the risen dead. Every time I saw those vans, some shining with the words West Bengal Undead Quarantine fresh-painted on them, I stopped to wonder whether I was remembering something from a movie or actually looking at something real. The cafe was relatively quiet—just a few afternoon customers chatting amid the burbling of espresso machines. But elsewhere in the city, people were striking and rioting to throw stones and claim their own religions and ideologies as responsible or not responsible for this cosmic prank. That very day, there had been a march on Prince Anwar Shah Road, by South City Mall, with fundamentalists of one or many stripes demanding that movies filled with immoral violence and sexuality be removed from the mall’s multiplex immediately in order to end God’s wrathful plague of the waking dead. The puritanical thrive in apocalypses.

The mother is a Hindi teacher at a small school. She took one sip of her coffee out of politeness. I had to ask her, after apologizing for doing so, “Did you recognize your daughter on TV that day?” She looked like she was out of breath or keeping down vomit. After a moment, she nodded. She did recognize her daughter. Of course she did.

I could understand the rest without her saying anything more. Who would want to acknowledge to themselves that their missing daughter was on TV, on the news, in real life, a walking corpse? That was too many impossibilities to deal with. I couldn’t bear to think what this woman, with her greying hair in a dishevelled bun, wearing an innocuous blue salwar kameez that made her look like any one of my high school teachers, was going through. I felt sick with her, the coffee acrid in my chest. Having had an abortion during college—one of the wisest decisions I’ve ever made—I wanted to say I knew how she felt. But remembering the brutal, almost physical depression of that distant time only furthered my remove from this woman, who had seen her adult daughter walking across the mud of the Hooghly naked as she had been in the first moments of her life, but dead.

I touched the mother’s hand, and she gasped as if terrified. We left the cafe in silence, her cup still full, cold on the table. My heart was racing just from being in the presence of such horror. Outside, the late winter sunlight did nothing to calm it. Thankfully, there were no marchers or black vans on Lansdowne. If we could forget for a moment, it might have felt like any other day in Kolkata, in that bygone world where the dead stayed dead.

I drove the mother to Kalighat in my old Maruti, and she slept through the ride. I got the impression sleeping was the easiest way for her to escape human interaction.

The stinking alleyways outside the temple were lined with the guru’s growing mass of followers. Many pressed their palms to the mother as we passed, and some tried to touch her feet. They knew who she was. She walked through them as if in a dream, not responding at all.

I had come prepared this time. We both wore surgical masks, and we’d both rubbed VapoRub under our noses. The hawkers still tried to sell us both.

Guru Yama sat in the courtyard inside, same as before. His wife sat at the altar, like a goddess of death next to her husband, who had been named after the god of death by his followers. She was covered all over in heaped garlands of sweet genda phool, so many that it looked like they were crude, thick robes. Her jaundiced eyes peered from between the petals, and a ballooning hand stuck out of the flowers, the orange circlet of a single marigold in its bulging palm. The smell of the garlands wasn’t enough to mask the stench of the festering body beneath them.

“Greetings,” the guru said to us, his eyelids drooping with antibiotics, with fever, with other drugs, or perhaps just spiritual ecstasy; I couldn’t tell. It had been three weeks since I had last visited him there. He sounded more confident and much calmer. His beard, too, was longer. More befitting a guru, I suppose.

His wife did not move, though the hand holding the flower quivered slightly, as an effigy’s straw limb might in a breeze. From under those flowers came the rattle of air passing through tissues, a soft groan. But she was unnaturally still. It made me realize how jarring it was to see a living animal that didn’t breathe.

“Don’t be afraid of her,” the guru said to the mother. “She is still your daughter. She has bitten me, yes; you see the bandages. But your daughter’s bite has made me feel more alive, Mother. I have infected myself with the poison of the dead so that I may live with them. It strengthens me. It gives me visions. Oh, Mother, don’t cry. Rejoice in this miracle, rejoice. She has a second chance in the world. She can’t talk; but in my visions, in my dreams, she speaks.” These were his first words to his mother-in-law (though certainly a dubious law).

“What does she tell you?” the mother asked, her breathing tortured.

“In my dreams she shows me the man who killed her. She tells me”—he lowers his voice—“the terrible things that were done to her. She shows me the face of the man so that he may be brought to justice if I ever see him in the world.”

Given the smell in the air, the situation we were in, I expected the mother to throw up at the sight of the guru and his wife or react adversely. But she just seemed catatonic as she stared at her daughter sitting on that altar, buried in flowers save for her purple face and bulging eyes. It isn’t accurate to say the mother didn’t react; her cheeks were covered in tears. They dripped off her chin, soaking into the surgical mask that flapped against her mouth with each heavy breath she took.

“Have you touched her?” the mother asked, very softly, and I felt a chill down my neck.

The guru smiled. “I have touched her, but not as a husband would. I have held her, and guided her, at times. It is not easy to touch her. She is fragile. But I understand your fear. We are married so that I may shelter her in this new life; that is all. I want to protect her, from men who would do what you are afraid of, from men who would take her and let her rot in a cell or a grave. I want to protect her from the birds in the sky and the dogs on the street.”

“I’m not afraid of what anyone will do to my daughter. They’ve already done what they will. Taken her. Taken her from me. Why is she like that? The flowers,” the mother said, out of breath.

“It helps with the smell. In summer, she would be gone by now. But she’s strong. She ate meat from the sacrificed goats, wanted to eat it. She tried to eat me, I think, when she first bit me. But it’s just a habit that she remembers. I saw the meat sit in her stomach and make it big, like a baby in her.”

Like a baby, I thought, and felt spots appear in my vision. I blinked them back, sweaty, the stench clinging to my throat.

“She threw up many times, and it was still just meat and maggots. The body will not take food in death. It rots in her. Eating is not good for her, I think. Now I don’t feed her. She is happier. She tells me when I’m asleep.”

I could see the mother’s hands trembling, grasped tightly together over her stomach, her womb. The mask was soaked through. “I’d thank you, Guru, if that’s what you call yourself,” she whispered.

“I’m sorry, Mother, I can’t hear very well; this fever fills my head. The poison of the bites has its toll, even if it’s a gift.”

“I said, I’d thank you, Guru, if that’s what you call yourself,” she said, voice shaking.

“That’s what they call me, Mother. Guru Yama. I’d be honoured if you called me son,” he said, bowing his head.

I glanced at the corpse. I saw its distended eyes move in their sockets, looking at us from under the coils of marigolds. I took shallow breaths.

“I’d thank you, Guru,” the mother said again, not calling him son, “for guarding my daughter from the kind of people who took her away from me. I’d thank you if I knew that you weren’t the one who killed her and threw her naked in the river, as if she were garbage.”

“No, Mother. No, no, no,” he said. He looked genuinely dismayed by this suggestion, his eyes widening.

“You found her; how do I know?” she asked, coughing. I flinched as her daughter rustled under the flowers, breaking from whatever mordant meditation she was suspended in.

I touched the mother’s shoulder. “Ma’am, there were witnesses who saw him finding her; she washed up on the ghat . . . ” I reminded her.

“What if that thing isn’t even my daughter?” she said, taking off her glasses.

“It is,” I whispered. “I looked at the footage, compared the photos. We can ask the police to do a DNA test, but I don’t know if that would work at this stage of decomposition. If you claim her, we can get her to a morgue before she starts falling apart completely.”

“No. I don’t want that. She’s already gone. That . . . . She doesn’t look like my daughter anymore,” she said, her voice so very small.

The creature under the flowers crooned as gas escaped her mouth. It sounded eerily like song, and who’s to say it wasn’t? I saw the guru look at her, and I noticed his eyes were wet as well. Was it the accusation? Empathy for her mother?

The corpse moved its fake-looking hand, the skin stretched like a latex glove half–blown up. And, to my shock, she raised that grotesque hand and wobbled the flower into her thick blue lips, eating it, the petals glowing bright against her black-and-brown teeth. The guru pointed. “Look: like I taught her, Mother. Like I taught her. I taught your daughter not to eat, and if she does, eat the flowers. Small, they don’t hurt her. Good, beta, good.” He grinned, the pride on his face clear. The guru looked like a boy showing his mother a trick he’d taught his pet.

The mother stared, and gasped with what sounded like laughter. She laughed, perhaps, and then she sobbed, sitting on the dirty ground of that courtyard. She sobbed and sobbed, scrunching the surgical mask into her face like a handkerchief as her daughter’s corpse munched on a marigold, and her unasked-for son-in-law held her hand with hope and fear in his eyes. The moment lasted barely a minute before she got up and asked to leave immediately. She had come to officially identify her daughter’s corpse, but she’d barely seen it. And yet, how could I force that? How could I ask that the flowers that hid that monstrous, infantile thing that was once her daughter be removed? I dreaded to see the decay, and so did she.

“I am sorry for your loss, Mother,” the guru said as we left, his voice different from how it had been.

“I want it burned. I can’t have that walking around. It’s not my daughter anymore. She’s gone. I want it burned,” the mother said to me in the car, once she had regained some of her composure.

I drove her back to her apartment. She remained silent the whole time. Once I had parked by her building, she turned to me, eyes swollen. She grasped my arm, the first time she’d touched me. She held me very tight.

“Miss Sen, do you think I made the right decision?” she asked.

Swallowing, I told her, “I don’t know, ma’am. I truly don’t.”

“I don’t think he killed my daughter,” she said, letting go of my arm. Her hand fell limp to her lap.

“I don’t think so either. I interviewed a lot of people who were at the ghat, both when he found the body and when he came back. Everyone confirms he was among the morning bathers when the body washed onto the ghat.”

She let out a long and heavy breath. “I don’t think it should be burned.”

I don’t know why, but I was relieved when she said that. I remembered those horrible, deformed hands lifting a flower to that rotting mouth, and my chest ached.

“All right,” I said, nodding too hard. “Whatever you feel is right, ma’am. And please, call me Paromita.”

She placed her fist against her forehead, her bangles jangling. Her eyes closed, she said, “He can keep it. You know”—she opened her eyes, looked at me—“my daughter never seemed interested in marriage. I know I asked her about it too much. I wanted grandchildren very much, a son-in-law. To fill up our family, you know? It was so empty when my husband left, even though he was just one person. So, I pestered her all the time to meet a man. She was still young, after all, but had no interest in weddings and children. Such a good student, always career-minded. She was so happy to go to college. Really, she wanted to go abroad to study. I didn’t have the money. I don’t know how much that hurt her, but she never, ever used it against me, even when we fought about things. And we did fight. College was good for her. She needed to live apart from me. But I missed her so much. She’d say, ‘Ma, that’s ridiculous; we live in the same city,’ so I didn’t tell her, but I missed her all the time. Honestly, I was grateful she didn’t go abroad, so that she could still visit me. And she did. She did, until she was missing. And then that was that. Now I don’t know what’s happening.”

“Nobody does,” I said. I put my hand, very lightly, on her arm, before returning it to the steering wheel.

“You’re not as young as my daughter,” she said. “But you’re young. You have so much energy, to be doing all this, figuring out who she was, finding me, when the police should be doing things like this. All this work, all this energy, when the whole world’s going mad. You should be very proud.”

“Thank you,” I said, my ears going hot. I felt suddenly ashamed to be alive in front of her, despite her kindness.

She took a crumpled handkerchief from her handbag and wiped her nose. “The person who killed my daughter, that person was unkind to her. Horrible to her. I don’t know . . . whatever animal her body has become, I don’t know what it feels. If it’s walking, eating, maybe it’ll feel the flames. I won’t be that unkind. I won’t, in my daughter’s honour. That man can keep the body, or whatever it is now. You’ll tell the police?”

“I will. They’ll call you and probably ask if you identified her. You’ll probably have to talk to your lawyer and get a death certificate. But I’ll tell them.”

I smiled, though she didn’t look at me, instead staring straight ahead through the windshield. “Thank you, Paromita. For everything you’ve done, are doing, for me, and for my daughter.”

I nodded, but found myself too choked up on my words to reply at first. I barely managed to say “You’re welcome” before she took her handbag and got out of the car. I’ve talked to her a few times on the phone since, to organize a meeting with her lawyer and the police, but that was the last time I saw her.

4. Notes on Death

I saw Guru Yama and his wife one last time at Kalighat. I went there to tell him he had the mother’s consent to keep the body. I had ad hoc legal papers from her lawyer giving the guru “official” custody of the walking cadaver. The guru thanked me, but his enthusiasm had turned to sadness, because his wife was on the verge of falling apart. She was attracting rats and other vermin into the temple, and dangerously close to liquefying. “I do have to burn her,” the Guru told me, dishevelled and weak, scratching at his bandages.

“You can give her to the hospitals, the research institutes, if you want to keep her from the police,” I said. “They can put her in cold storage.”

He shook his head. “No, Miss Sen. Maybe if she was younger. The dead have short lives. This I know now. She would suffer a lot if they tried to freeze her now.” He had decided. Perhaps because of his meeting with the mother. Perhaps not.

He used her rope leash to lead her from the altar to a hired lorry. By now, she was barely able to walk, waddling slowly and leaving a trail of dark brown droplets that her garlands dragged into smears. Men with mops swept the trail away as she was led across the courtyard. The walk took half an hour. The guru draped a cloth over her face so all the people they passed didn’t panic her. Dragging her flower garlands, she was lifted into the back of the lorry in a large blanket, five sweating men heaving at its sides and rolling her in with no dignity. I followed the lorry to the Garia crematorium.

I waited in the crematorium’s cold, shadowy halls as the guru’s wife was taken in for incineration.

The worst thing I have ever heard in my life was the brief scream that rang out through the crematorium, sharp and human, before being lost in the hum of the ovens. I went outside to find a dog barking furiously in the courtyard, drool flying into the dirt. I leaned against the yellow walls of the building and waited.

The guru emerged and thanked me again.

“That scream—was that her?” I asked.

He nodded. “It’s good. It’s good that her mother wasn’t here.” I saw his hands shaking like the mother’s had.

“What’ll you do now?” I asked.

“I’ll find more of the dead who need my help. Other people want to give me their dead, to take care of, to speak to in my visions. I have followers. I’ll never let one of the dead down like this again. One day, Miss Sen, I’ll be a big guru, like the ones you see on TV, in the newspapers. I’ll have money. When I do, I’ll buy one of those resorts, those hotels in the mountains, high up. In the Himalayas or”—he paused, then spoke carefully—“Switzerland. I saw them in magazines. It’s always cold, and they’re huge. There, my dead can roam free, and live longer. You watch; you’ll see. Away from all these people trying to take them, away from police. They’ll be happy there.”

I wished him luck as he walked back to his followers, looking strange without his wife by his side. In my car, I cried quietly for that walking corpse, as if I were crying for the woman who had died in its body.

Guru Yama doesn’t yet have a Swiss ski resort for his dead. He does have an ashram in Uluberia, with refrigerated chambers for his “children” (no more wives or husbands, to reduce the accusations of necrophilia). He keeps himself in a perpetual state of fever, allowing his children to bite him every month, staving off death and resurrection via antibiotics paid for by his followers and clients. Detractors of dead-charmers say that the visions and dreams through which they talk to the dead are nothing but delirium brought about by fever and drugs, including heroin and hash taken for the pain. I plan, one day soon, to do a book of photo essays with my friend Saptarshi about him and his flocks, dead and alive.

I still don’t know whether he’s a charlatan, or deluded, or a prophet.

Perhaps because I’m an atheist, I’ve never trusted charismatic religious figures who use their influence to gather wealth. I don’t quite recognize the man I see in videos and pictures now, covered in ash, turmeric paste and bandages, cloaked in hash and incense smoke, beard hanging down to his hollow stomach, surrounded by veiled corpses like a true lord of death. But I remember the man who walked out of Garia crematorium, his shaking hands, his shocked stare. His grief for the creature he called his wife was so very real. We both heard her scream as she died a second time.

The thing about the reality of the undead is that we can now see the afterlife. We live in it. And we share that afterlife with its dead inhabitants, who walk among us. But we can’t talk to them, and they can’t talk to us. That truly is the most exquisite, atheistic hell.

5. Notes on Afterlife

Visiting my parents is different now. Now, when I drink tea with them on their veranda, tea that somehow tastes of my childhood even though it’s just plain old Darjeeling, I watch them age gently next to me. More than ever, every new wrinkle, every new wince of bodily pain, every glimmer of sun off a newly silvered strand of hair catches my eye. And I can’t help but think of the future.

In this, should I say, apocalyptic future, I have to sign a form by their deathbeds. The form asks if their death is to be final, if I want to authorize doctors to sever their brain stems and puncture each lobe right after their hearts stop beating, to make sure they won’t rise up again in undeath. There are two other options: I can illegally have them bitten by a corpse belonging to a dead-charmer before they die, to increase their chances of resurrection. Or I can take a cosmic gamble and let the universe decide between two terrible things by checking the other box on the form that says my parents should be left untouched after death, to see if their bodies naturally choose undeath. The undead will not be allowed in homes because of numerous health hazards including dangerous, often lethal, bites. So if my parents rise into undeath it will fall to me to hand them over to the government or a private scientific institution, or a dead-charmer.

This is the future. Governments are already trying to figure out appropriate legislation for the realities of dead people waking up and creating an entirely new kind of life.

I think about simply losing my parents forever, once the only choice. Then I think of them undead. And I think of Guru Yama’s wife, grotesque and alien, death itself personified as a gigantic, corpulent infant, crooning to itself and eating a single marigold as I struggled to understand whether its painfully corrupted form caused it pain. I think of it screaming in an oven.

I see myself, pen hovering over the forms, not knowing which box to check.

Who am I to deny someone I love a second life, however incomprehensible, however different from the first? And then, with both relief and panic, I realize it’s not even my choice, but my parents’. One day, I’ll have to have a conversation with them about whether or not they want to risk becoming a fucking zombie. I haven’t asked yet.

And one day, when I have a child—if I have a child—I’ll have to have that conversation again, when they ask me.

When these thoughts creep into those evening conversations with my parents, tinting them with dread, I think of two corpses shambling up a snow-clad mountain in Switzerland, their flesh preserved in a fur of frost that glitters under a high, clear sun, their thoughts unfathomable.

“Breaking Water” copyright © 2016 by Indrapramit Das

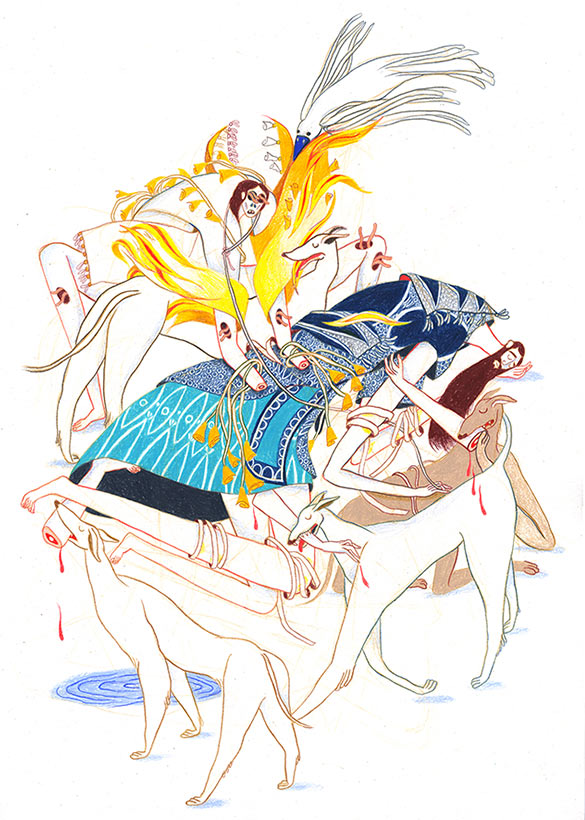

Art copyright © 2016 by Keren Katz