C.A. Higgins’ Lightless begins aboard a unique spaceship, the Ananke, that has a black hole for a heart. That’s how Althea Bastet sees it, anyway. Though she’s the ship’s engineer, her practical skills are tangled up with her affection for the ship she thinks of as hers. The black hole powers the ship and its purpose, but Althea dreams that of the black hole as a heart, a bloody, embodied thing.

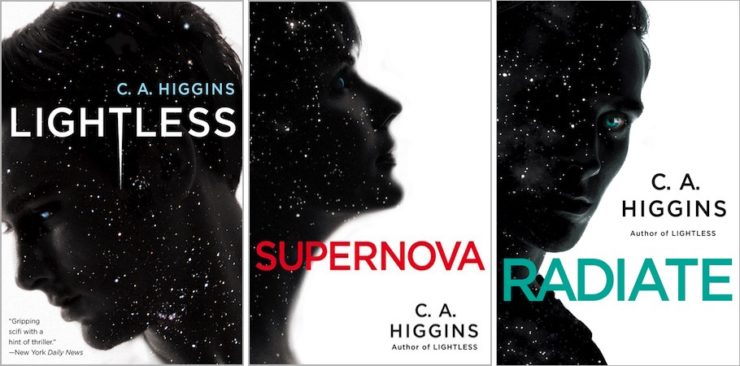

Althea can tell when something is wrong aboard her ship, and at the opening of Higgins’ series, she knows. Lightless takes places entirely aboard the Ananke; it’s not exactly a locked-ship story, as other characters come and go, but the cat-and-mouse game that drives one of its storylines makes the ship feel claustrophobic. But Lightless is only the first in the trilogy, and while Higgins’ tale never leaves the Ananke entirely, the subsequent books—Supernova and the closing Radiate, which comes out next week—spread across the entire solar system. It’s a surprise, to move from Lightless’s narrow hallways to the surface of Mars and beyond, but Higgins’ shifts in viewpoint are effortless. She seeds each book’s story in the pages of the previous books, connecting everyone in a narrative that loops back on itself. Though the perspective is different, Radiate begins where the action of Lightless starts: with Matthew Gale (called Mattie) and Leontios Ivanov (called Ivan) boarding the Ananke.

Some spoilers for Lightless and general discussion of Supernova and Radiate follow.

I grew up reading mostly fantasy, with only small servings of science fiction, and though my tastes have changed, this early habit means I’m not picky about the science of my sci-fi; it’s all magic to me. Higgins, though, has a degree in astrophysics, and so I trust her science as far as I can faintly grasp it. Her future is believable: people have colonized space, but class divisions remain; light-speed travel is possible, but can be dangerous; the wide network of the governing body, the System, is useful even as it’s keeping tabs on you. Althea spends a lot of time at computer terminals, and none of it is boring; the character’s love for her work is, in Higgins’ hands, the stuff of beautiful writing and just enough technical detail to keep the reader engaged but not overwhelmed.

But Higgins also does a smart thing for her more magically or mythically inclined readers: a loose mythological thread weaves through her series, triggering associations for those of us who grew up on, say, Lloyd Alexander’s Chronicles of Prydain. A ship called the Annwn is not captained by Arawn, but Arawn appears in the story (another character wonders if he’s named for a planetary region, or if the name is older than that). A woman who fights against the oppressive, inescapable System calls herself the Mallt-y-Nos; “Matilda of the Night,” named after a mythological woman who rode with the Wild Hunt.

Higgins isn’t always literal with her mythological references, but they’re there, and they emphasize the way the Mallt-y-Nos—whose identity is one of the secrets of Lightless—needs a story. What she takes from her namesake’s myth, though, might not be the same thing we see connecting them. Also called the Huntress, the Mallt-y-Nos is a freedom fighter to some, but a terrorist to the System, which rules everything with a camera-toting fist. Surveillance is omnipresent. The System knows all. The System controls all.

The System is less developed than those who fight against it, but its influence is felt from the series’ first pages, when Althea and her crewmates must report everything happening aboard the ship. The name Ananke, too, is from mythology, and her name is absolutely a clue to her fate: Ananke was a self-formed being, the consort of Chronos, the personification of necessity.

This Ananke is something else. Part of Lightless’s plot follows an interrogation—when the ship’s crew captures Ivan, System intelligence agent Ida Stays comes to question him. Ida believes she is always right; she also believes she’s in control of a situation that has slipped free of anyone’s control. Something is wrong with the ship, something that Althea cannot figure out, for all her brilliance. Because before Matthew Gale slipped away from the ship’s crew, he did something to the computer. It’s a tactic he’s used before—and one Ivan can explain to Althea, if she’ll give him something in return.

But Mattie has never encountered a computer like this. The Ananke, with her black hole heart, is built for a specific, secret purpose. Mattie, unknowingly, gives the ship a push that leads her to do something improbable: She stops being the Ananke and becomes just Ananke. Sentient, intelligent, Ananke is born of Althea’s brilliance—and Mattie Gale’s chaotic contribution. Her awakening is not easy, and why would it be? There is no other being like Ananke, and all she has to witness—all the behavior she sees through the System cameras in every room—is violence. Interrogation, arguments, power grabs, bargaining.

Ananke is an utter terror, and parts of the book are rather like that Mr. Robot episode when the lawyer’s smart-home turns on her—just much deadlier, and in the vastness of space. But after Higgins sets this scene, introducing a childish, powerful AI who is learning horrible behavior by example, she changes the focus. Lightless comes to a solid, difficult, painful end, but it isn’t the end of the story, nor of Higgins’ focus on the forces that shape us.

Supernova shifts much of the story to Constance Harper, Matthew Gale’s foster sister and Ivan’s sometime lover. Constance makes a brief appearance in book one, but it’s a surprise to open Supernova and find that we’re with her more often than not. Her story is harder not to spoil, but as with Ananke, Higgins explores how a person’s environment, the world in which they’re raised, might make them who they are. There are no right answers: Constance and Matthew grew up together, but are wildly different. Ivan, the son of a famous revolutionary, is a whole different case.

Supernova takes a tough look at actions and consequences, and how we understand the relationship between the two. At what point does a revolutionary become the System they’re fighting? When does violence on behalf of freedom just become more violence? How does a person—or an AI—come to understand right and wrong? What do you do when something you started grows too big to control? How do you surround yourself with the people you need to balance you? How does a consciousness process a set of inputs and decide what to do with them? And how much do you owe your family, chosen or otherwise?

The idea of family nestles itself into Ananke’s mind: Althea is her mother, Mattie Gale her father, and she wants them both. She also wants not to be the only one of her kind, but doesn’t understand that there are no others like her. In Lightless I constantly wanted the story to go back to Althea, much more interested in her than in Ida Stays’ interrogation of Ivan (though Ivan’s carefully doled-out answers reveal much about the System). By Supernova, I almost wanted the story to stay with Constance, so as not to have to see the hopelessness of Althea’s arguments with petulant, tyrannical Ananke.

Higgins writes beautiful, complicated, argumentative, frustrating, imperfect, irreplaceable family connections, whether between Constance and Mattie; Ivan and his preternaturally calm mother, Milla; or even Althea and the unmoveable, unbeatable creation she thinks of as her daughter. Ananke is no child, but Althea feels responsible for her and her destructive choices. She thinks of the ship as hers, and tries to assert the authority of a mother over her child. It makes a kind of sense, since Ananke refers to Mattie and Althea as her parents, but can you argue with an AI by appealing to its feelings, by asking it to be good? What is good to a machine? Their relationship is crushing, and I don’t recommend looking up the mythological origins of Althea’s name unless you want a pretty major clue as to how that part of the story goes.

Althea has one notable weakness as a character, and it’s that she reads as younger than she is. Though she’s been out of university for twelve years, which puts her roughly in her early 30s, she reads like a much younger person, a trait I chalk up to her relative isolation aboard the Ananke and her intense focus on the ship. It can be hard to gauge the age of Higgins’ characters, who all seem basically the same, excepting perhaps the teen revolutionary Marisol Brahe. It’s a small critique, though, in a captivating series. And the most interesting family are pretty close in age: the trio of Constance, Mattie, and Ivan, all of whom think they belong to each other in different ways, and all of whom are both right and wrong.

Supernova ends on a dark note, with one of the most difficult scenes I’ve read in recent years. With Radiate, Higgins changes direction again, picking up the story of Ivan and Mattie. Supernova does some jumping around in time, filling in some of the history of Ivan, Mattie, and Constance—but Radiate, in a structure borrowed from (among other things) Iain M. Banks’ Use of Weapons, moves backwards and forwards in turns. One narrative follows Mattie and Ivan as they try to catch up to Constance, while the other traces their relationship back to where it started.

Radiate has a lot of work to do; what becomes of Constance, and of Althea and Ananke; what of the Mallt-y-Nos’s revolution, and the changes it wreaks upon the worlds? By focusing mostly on Mattie and Ivan, and showing Ananke’s actions from their perspective, Higgins keeps the spotlight on how individuals react to world-shattering change. As the story moves backwards, so many interactions take on shading and color, particularly the push-pull, love-love (as opposed to love-hate) moments that Constance, Mattie and Ivan are so often caught in. What choices would you make for a person you love? What lines would you cross or not cross? And what does love look like, in a damaged, controlled world?

Higgins never lets anyone off easy, but what makes the closing volume of this series so ultimately affecting is that she also never puts anyone in a box. There’s no need to define what Ivan is to Constance, or what Ivan is to Mattie; to depict this circle of connections with boundaries and rules would strip it of the nebulous, believable, constantly changing shape that makes it what it is. Does Althea stop loving her ship when it turns deadly? Does Mattie love Constance any less when she makes a deadly decision? Does Ivan have to love one of his companions more than the other? Can love be terrible and still be love?

When Radiate winds down, it’s as much interpersonal drama as space opera, though the scale is still huge. Space is full of dead ships; planetary greenhouses have cracked and broken; one planet is uninhabitable. The solar system has changed as a the result of these characters’ actions—but they’ve lost control of the changes. In shifting timelines and shifting alliances, each character comes to grips with that,and with each other, and what the worlds will look like in their wake. The Lightless trilogy tells a story about lives caught up in something bigger than themselves, and bigger, even, than all of them together—and how you cannot get through catastrophic change alone. For all the time these characters spend careening through space, often alone, these books are anything but lonely.

Molly Templeton is Tor.com’s publicity coordinator. She also writes about movies for the Eugene Weekly, and talks about a lot of things on Twitter and elsewhere on the internet.