I heard a powerful interview on CBC Radio’s literary show, The Next Chapter one day, and I’ve been thinking about pain ever since.

Shelagh Rogers, the host, was interviewing Joshua Whitehead, an Oji-Cree, Two-Spirit scholar from the Peguis First Nation on Treaty 1 territory in Manitoba. He’s also the acclaimed author of the novel Johnny Appleseed. At some point in the interview, he talked about pain—but not in the way you think.

The main character of his novel, the titular Johnny, is a reflection of the kinds of violence indigenous youths are subjected to, and particularly the kind of sexual trauma indigenous communities continue to deal with as a result of Canada’s residential school system. But Joshua voiced a way of thinking about pain I hadn’t considered. As he explains, Cree language imbues various ‘objects’ with spirit: rivers, rocks and even the planet itself. But what about pain? Joshua poses the question to Shelagh: “if we can animate our pain, is that something we can make love to? If we can take pain and make love to it, can it transform into something that’s kind of healing?”

Pain is a subject often discussed in Black literary communities precisely because it often feels like the media is preoccupied with Black pain. As Dr. Sonja Cherry-Paul wrote for Chalkbeat National, “books can serve as mirrors that reflect the racial and cultural identities of the reader. Yet historically and presently, there have been too few books that…center Black joy.”

But what if, like Joshua Whitehead, we think about pain and joy in a way that doesn’t consider them as strict dichotomies? As Bethany C. Morrow has argued, BIPOC writers can often make a kind of distinction that publishing as a whole cannot. Thinking about this further, I think the reason why the industry may be less equipped to see nuance in Black experiences has a lot to do with the fact that publishing is a highly racialized space. Statistics from Lee & Low Books show that American publishing is nearly 80% white.

This matters. It matters because we live in a racialized society, a society that has deep-seated understandings about what it means to be Black. A history of imperialism, colonialism and slavery has constructed what ‘Blackness’ is for the white imagination. And as theorist Sherene Razack states in her book, Dark Threats and White Knights, the larger cultural narrative in North America tends to relegate Blackness to the realm of the abject. This includes circulating stories of Black brutalization, but as Razack argues, such narratives of Black pain rarely prioritize Black subjectivity; rather, as with stories of genocide, gang violence, slavery and so on, Black pain is often portrayed as a spectacle for the assumed white subject’s consumption.

In her piece, Playing in the Dark: Whiteness and the Literary Imagination, Toni Morrison links culture and history to the American publishing industry, arguing that the work it publishes is always already inflected by gendered and racialized cultural narratives circulating in society, whether writers realize it or not. She criticizes the idea held by some literary historians that “American literature is free of, uniformed, and unshaped by the four-hundred-year-old presence of, first, Africans and then African-Americans in the United States.” And really, think about it. How can anyone argue that the presence of Blackness, “which shaped the body politic, the Constitution, and the entire history of the culture” has had “no significant place or consequence in the origin and development of that culture’s literature”?

Society has problems with how to represent Blackness. It shows in the publishing industry, it shows in the news, TV and film. I myself, as a Black Young Adult Fantasy author, have reflected in a personal essay that oftentimes, being a Black writer in the publishing industry means having to navigate the viewpoints of white consumers and publishers who have their own restrictive definitions of what ‘Blackness’ in books must look like and boy, can this ever take a toll on one’s psyche. A report by The New York Times about the lack of diversity in American publishing certainly showcases the ways in which Black authors are entangled in the very same systems of oppression about which we write. According to an interview given by a former editor, we almost didn’t get Angie Thomas’s blockbuster hit The Hate U Give because the editorial team felt like they already had enough Black authors on their roster. Likewise, #PublishingPaidMe, started by Black fantasy author LL McKinney, revealed how Black authors are inadequately paid, promoted and marketed compared to our white counterparts.

But thankfully, Black writers are challenging centuries-long depictions of Black pain for pain’s sake and Black pain for the white gaze, by writing the reality of pain with the kind of nuance that creates space for catharsis, transformation and even healing. In particular, Black writing in SFF offers an intriguing perspective on the complexities of pain and joy.

The Reality of Bigotry in Fantasy

Fantastical modes of writing can explore difficult realities in creative ways. It allows readers to enter into lived experiences through a non-traditional vantage point. Through wonder, imagination and enchantment, readers can be opened up to the complexities and nuances of what marginalized people experience every day. Many of us Black SFF writers are not only exploring the power dynamics our characters are confronting; we’re writing in response to the pressures we ourselves experience, and that includes everyday racism, sexism and bigotry.

Black SFF writers channel the uncomfortable truths of their realities in plots and settings that make these struggles no less real; indeed, fantastical elements can make these truths feel hyper-real.

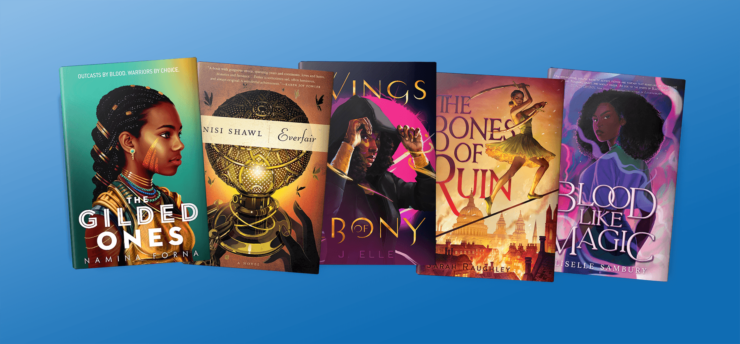

Namina Forna, author of The Gilded Ones, is a graduate of Spelman, the historically all-black liberal arts college for women and one can see her feminist ideals reflected in her Afrocentric story about young women feared by their communities. In this world, just as in ours, Black women’s acceptance into society depends upon their adherence to society’s ideals. For Sixteen-year-old Deka, whether or not she fits society’s norms is literally determined by the color of her blood. Those with gold blood are considered unclean, but it is her people’s definition of ‘uncleanliness’ that adds to the dimensions of Deka’s story. Women with gold blood are immortals with wondrous gifts that can only be killed if one finds their one weak spot.

It is their power—a woman’s uncontrollable power—that deems them unfit to belong in their patriarchal communities. Once their golden blood is discovered, they have two choices: accept death or let the empire use their power for its own purposes. The pain of being ostracized, of having your submission be a requirement for your belonging in a community is explored in The Gilded Ones. The novel gives insight into how a patriarchy maintains its power. Coming from the Temne tribe of Sierra Leone and living in America, Forna seems to understand that the problem of patriarchy is transnational, bearing down upon women locally, nationally and internationally. Deka undergoes torture at the hands of her community and even upon being conscripted into the alaki, her empire’s all-female indentured military, she continues to experience various physical and emotional abuses, the kind that comes along with having to fight terrifying monsters on behalf of an oppressive regime.

The novel’s subject matter is quite weighty, never letting readers be simply a spectator to Deka’s pain, but forcing them to understand and acknowledge her subjectivity. It is through her trauma and circumstances that Deka finds a community of her own. And though the scars of this trauma do not and cannot simply disappear, it’s important that she has a community of people who understand. This is made clear during a scene in Chapter 25, in which Deka speaks to another alaki, Belcalis about their shared physical scars: “Once I stopped being hurt, being violated, they faded,” Belcalis says. “And that’s the worst part of it. The physical body—it heals. The scars fade. But the memories are forever…They may need us now because we’re valuable, might pretend to accept us, to reward us—but never forget what they did to us first.”

Forna shows that a kind of resilience is made possible through receiving empathy and understanding from others who share your experiences. By using fantasy to shine a light on the power structures real Black women are entangled in, Forna provides a story about communities of women and the ability to turn pain into the will to fight back.

J.Elle’s Wings of Ebony likewise highlights the strength of her main character Rue who, despite being a half-god, faces circumstances that many Black readers today may identify with. As Black people, we live in a society that targets us and our loved ones for brutalization and death. Rue’s mother is shot and killed in front of her home. Rue’s neighborhood, East Row, is no stranger to senseless death, what with violence and gangs running rampant. But the circumstances surrounding her mother’s murder are far more mysterious than one might assume. This becomes clear when her absentee father shows up out-of-the-blue to take her to a foreign land against her will: Ghizon, a magical world hidden from human sight. But just as in our world, the powerful entities of Wings of Ebony keep minority communities downtrodden, suffering and oppressed for the continuance of their own power—which is why at the end of the book it is exactly these oppressed communities that the villain needs to answer to at the end of the novel. The story isn’t just about defeating the bad guy, but about making sure he is held accountable. It’s this confession to Rue’s community, East Row, that becomes a moment of justice and truth that opens the door to healing.

J.Elle’s bestseller gives readers a way to confront the pain and ugliness of reality while offering hope through Rue, who breaks free from the limitations placed upon her to save her loved ones. It’s the kind of hope one receives when they realize they may not be valued by everyone, but they are valued, by their loved ones, by their community, and by their ancestors. Hope is key: the hope that a Black girl can rise above the pathological narratives forced upon her, the hope that one Black girl is enough to change her world. And as a Black girl myself, I see myself in Rue— a girl whose hair cries out for coconut oil. A girl who isn’t and should never be satisfied with the bare minimum from the people around her. A girl who was always enough.

Excavating Histories

But the anti-Black ugliness of today’s world doesn’t exist in a vacuum: it’s a result of a history of colonialism, oppression and imperialism that has had lasting consequences in how Black people are perceived and treated. Unfortunately, so many of these histories have been carefully covered up, buried in order to be forgotten by time. If we forget the past, we can’t learn the lessons needed to improve our futures. That’s why it’s so important that Black SFF authors are tackling these hidden histories head on.

Nisi Shawl’s Everfair, for example, tackles the bloody history of Belgium’s colonization of the Congo in the 19th century. While the misery of the Trans-Atlantic slave trade is more widely known, Europe’s colonization of Africa is often under-taught and understudied. When famous postcolonial scholars like Mahmood Mamdani stress that one can link the genocidal apparatus of the Holocaust to the murderous, race-based policies previously employed in African colonies, that’s a signal for all of us to wake up and pay attention to what’s been buried. Philosopher Hanna Arendt, in her book The Origins of Totalitarianism, also discusses the colonial brutalities you likely didn’t learn about in class, like the “elimination of Hottentot tribes, the wild murdering by Carl Peters in German Southwest Africa,” and, she writes, “the decimation of the peaceful Congo population—from 20 to 40 million reduced to 8 million people.”

Nisi Shawl looks at this tragic history with an SFF twist, chronicling the thirty year history of an imaginary steampunk nation in the Congo: the titular Everfair. Just like most steampunk novels, it is an alternate history, what-if story. It asks readers, how might the Congolese have responded to the murderous King Leopold and Belgium’s colonization of Congo if they had discovered steam technology earlier? In the book, socialists and missionaries buy land in the Congo and start a safe haven for Congolese people and escaped slaves from other countries right under King Leopold’s nose. Each chapter is like a short story detailing the lives of the multicultural inhabitants of Everfair as they live out their lives. The book details the attempt to build a just and peaceful society. For example, through steampunk technology mechanical replacements are created for the hands of Congolese laborers chopped off by their Belgian employers due to King Leopold’s violent policies. The book offers a kind of corrective history for readers still suffering under the weight of those colonial histories. But it also cautions the reader about power and nation-building. When well-meaning Western liberals provide resources to build the nation, but then simultaneously try to impose their language and culture upon the Africans they are ‘saving,’ Shawl reminds us of the different ways in which racism can rear its ugly head even in humanitarian contexts.

We are living in the UN International Decade for People of African Descent. You probably didn’t know that, because the United Nations has done a pretty terrible job in promoting it or doing anything with it. In 2019, I organized a conference to bring the Decade to light and discuss its three main issues: justice, development and recognition. And what these discussions made clear is that without recognition—recognition of history—neither justice or development can truly follow. For me who’s struggled with the knowledge that so much violence against the Black diaspora has gone unanswered for, reading stories find new, clever ways to excavate these truths is incredibly satisfying. The justice of recognition can lead to one’s peace.

It is this spirit of excavating buried histories that inspired my upcoming novel, The Bones of Ruin, also an alternate history Victorian era fantasy. The story of Sarah Baartman was the spark that got me writing—Sarah Baartman, a young woman brought out of South Africa under false pretenses and put on display like an animal in freak shows as ‘The Hottentot Venus’ for the pleasure of leering European audiences. Many people know her story, but few people know just how prevalent human exhibitions were in the Western World. In Europe and North America during the 19th and 20th centuries, people flocked to see racial minorities, including Africans, on display in zoos even up until the 1930s. In The Bones of Ruin, Iris is an immortal African tightrope dancer with a history that includes her display and objectification. But as Iris participates in a bloody apocalyptic tournament, as she struggles to learn the truth of her identity, she not only fights other supernatural misfits—she fights to reclaim her body from those who attempt to own it. Iris’s battle for agency reflects how difficult it is for Black women to claim ownership over our bodies in a society built upon selling and brutalizing it. But by reminding readers of the ways in which our violent colonial past is still present, books can shed light on the battles of today and provide authors and readers alike a model for how to overcome the restraints that have held us back.

Conclusion: Decolonizing Narratives

And can’t that lead to Black joy? Of course, we must be careful not to glorify the stereotype of the strong Black woman. And books about pure joy without suffering are indeed necessary, beautiful and healing. But we can advocate for a shift in the kind of analytical framework that would posit joy and pain as being uncompromising, irreconcilable opposites. I am advocating for understanding that pain, if it is experienced, can be a possible gateway to justice, peace and joy. That is not guaranteed. It is never guaranteed. But that it is even possible means something.

That there exist books that deal with the nuances of Black agency and subjectivity, written by Black authors, is itself a joy, especially for Black readers who need it. Liselle Sambury’s dedication at the beginning of her SFF book, Blood Like Magic, makes this point clear: “To Black girls everywhere,” she writes, “You can be more than a slave or a lesson for someone else…You are the hero.” These are stories not meant to provide mere spectacles for consumption, but hope for the marginalized from the perspective of the marginalized. And that last part is important. Readers are reading these stories of Black strife, healing and strength through the framework of Black perspectives, as diverse as those perspectives can be.

There are so many ways in which SFF books by Black authors can open up a pathway for the transformation of traumas into joy, catharsis and healing. But the key here, is that these stories must be written on the authors’ terms. It must showcase their preoccupations, their politics, their viewpoints and voices.

We are Black SFF writers. We’re here writing. And our words can heal. Just read our books and you’ll see the difference in how others handle our pain and how we do.

Sarah Raughley grew up in Southern Ontario writing stories about freakish little girls with powers because she secretly wanted to be one. She is a huge fangirl of anything from manga to sci-fi fantasy TV to Japanese role-playing games and other geeky things, all of which have largely inspired her writing. Sarah has been nominated for the Aurora Award for Best YA Novel and works in the community doing writing workshops for youths and adults. On top of being a YA writer, Sarah has a PhD in English, which makes her a doctor, so it turns out she didn’t have to go to medical school after all. As an academic, Sarah has taught undergraduate courses and acted as a postdoctoral fellow. Her research concerns representations of race and gender in popular media culture, youth culture, and postcolonialism. She has written and edited articles in political, cultural, and academic publications. She continues to use her voice for good. You can find her online at her website.